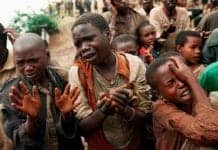

As voting time, set for Aug. 9, approaches, President Paul Kagame’s RPF continues to practice zero-sum politics that could lead to more political violence

by Susan Thomson

(Co-authored by a Rwandan academic based in the U.S. who survived the 1994 genocide and wishes to remain anonymous. This author runs the blog The Cry for Freedom in Rwanda.)

Kagame’s RPF emerged victorious from and gained credit for ending the 1994 genocide in which ethnic Hutu killed at least 500,000 ethnic Tutsi. Foreign leaders, feeling guilty for not having done enough to end the genocide or for having a direct role in the massacres, pumped money into Rwanda in the hope of rebuilding a new society – a society free from ethnic division. From ashes, the Rwandan people quickly started showing signs of recovery. Still, the RPF continues to practice zero-sum politics that could return the country to the abyss of 1994.

Over the last 16 years, the RPF has centralized power into a one-man dictatorship. A tiny English-speaking Tutsi elite, most of whom grew up as refugees in neighboring Uganda, surrounds the dictator, Paul Kagame. The politics of exclusion that marked the pre-genocide years remains intact despite the official policy of ethnic unity. The Hutu community, making up some 85 per cent of the population, is largely excluded from most positions of power. Even more insulting, politics, business and the civil service are all dominated by military personnel or former members of the RPF.

In advance of the upcoming presidential elections, many “friends” of Rwanda have remained supportive of its so-called “democratic transition.” They ignore the repeated arrests of journalists and opposition politicians, the closing of independent local newspapers, the ejection of a Human Rights Watch researcher, an assassination attempt against exiled Gen. Kayumba Nyamwasa, who fell out with President Kagame earlier this year, the murder of journalist Jean-Leonard Rugambage, who attempted to report on Nyamwasa’s assassination attempt in the online version of a Rwandan newspaper the print edition of which the government closed down, and the murder of Andre Kagwa Rwisereka, vice-president of the opposition Democratic Green party. While diplomats from some countries, such as Sweden and the Netherlands, have cut their aid, the U.S. and the U.K. continue to publicly support Kagame. Canada’s position is vague as it encourages Rwanda to adopt policies that promote a pluralist society.

Under the watch of a sympathetic and supportive international community, Kagame has done everything within his power to ensure that the August elections consolidate his political power.

First, he appointed all the members of the National Electoral Commission, staffing it with former and current members of the RPF. Although members of the political opposition have protested, Kagame shows no sign of accepting reform. Such an arrangement will make it possible for him to manipulate, rig and control the elections.

Second, the RPF revised the constitution in 2003. Many of its provisions endanger democracy. The most damning is the ill-defined law on genocide ideology. Its official purpose is to identify individuals who wish to kill ethnic Tutsi. In practice, the law is invoked against political opponents or critics of the government who question its reconstruction or reconciliation policies or who suggest that the RPF committed war crimes before, during, and after the genocide. Instead of erasing the ethnic hatred that the RPF believes lives in the hearts and minds of some Rwandans, the genocide ideology law is crystallizing dissent among some sections of the military while weakening the opposition and journalists who criticize the government’s application of the law.

Lastly, Kagame abolished real opposition and manufactured a shadow opposition that serves only to sing the praises of the RPF. This “opposition” is active only during election season and is otherwise unknown to the general public. None of the three actual opposition parties – the Democratic Green Party of Rwanda, FDU-Inkingi and PS-Imberakuri – can take part in the elections because their respective leaders are either in prison or banned from registering their candidates on allegations of harboring genocide ideology.

While much of the diplomatic community acknowledges these democratic shortcomings, most Western donors continue to highlight Rwanda’s economic growth as the necessary stimulant to inch the country towards democracy. What these actors overlook is the fact that the benefits of economic growth accrue largely to urban elites. The post-genocide policies of the RPF neglect the rural peasantry, which comprise 90 per cent of the population.

The international community widely praises Kagame’s liberal economic policies without due regard to the restrictions they have placed on what peasants produce and how they sell it. The government requires rural farmers to grow coffee and tea instead of the crops needed to feed their families. A new land policy has decreased peasant holdings to less than a half-acre. This means that few families are able to grow enough to subsist, let alone take any excess to market.

The United Nations Development Program reported in 2008 that Rwanda’s Gini coefficient has increased since the RPF came to office, and that the socio-economic disparity had increased from its 1990 levels. As one rural farmer in Northern Province lamented, “If the RPF doesn’t allow us to trade freely, we will join the FDLR rebel group … otherwise, how will we feed our children?”

The suppression of democratic ideals under President Kagame cannot guarantee continued economic growth in Rwanda. The latest attacks on basic human freedoms could be but the tip of the iceberg. Before Rwandans go to the polls next month, Western friends of Rwanda – the diplomats, policy-makers and academics that extol the country’s democratic virtues – must press for meaningful democratic change by encouraging free speech and political dialogue with a viable opposition. Without meaningful change, the country could be headed for another round of mass political violence.

Susan Thomson is a Five Colleges Professor, funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation at Hampshire College, Amherst, Mass. She has been researching state-society relations in Rwanda since 1996 and is the author of numerous publications on the country. She can be reached at susanm.thomson@gmail.com.

Store

Store