by Laura Flynn

A Haitian friend recounted this story to me this week. It was an image that she could not get out of her head since Jean Claude Duvalier returned to Haiti. Because that’s what it was like for her to watch Duvalier be greeted like a dignitary at the Port au Prince airport and then escorted to his hotel by U.N. military forces – like being burned alive.

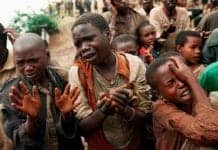

In 1968, when my friend was 3 years old, members of Duvalier’s Ton Ton Macoutes came to her home at 3 o’clock in the afternoon as her extended family shared a meal in the courtyard of their house in the Port au Prince neighborhood of Martissant. The Macoutes dragged her father and two of her uncles away. They then went to two other houses on her block and took away all the men from those families as well. Her father and the other men in the neighborhood were members of MOP, the mass political party of Haitian populist leader Daniel Fignolé, which Duvalier wiped out, along with all other forces of opposition in the country.

None of the men taken from Martissant that day were ever seen again. They disappeared, perhaps perishing in the Duvaliers’ infamous prison, Fort Dimanche, after enduring torture, beatings and starvation. The families could not even hold public funerals, and they never recovered the bodies of their loved ones. With the help of a sympathetic nun, my friend’s mother did manage a clandestine mass for her husband, and later she consecrated an unmarked, empty tomb for him in Haiti’s National Cemetery. To this day, she visits that empty tomb on All Spirits Day each year to honor the husband she lost over 40 years ago.

The common wisdom, repeated endlessly in the international press since Duvalier’s return, is that Baby Doc’s regime was less repressive than his father’s. But my friend’s mother does not remember it that way. Left to raise six children on her own, she lived for nearly 20 years – until the fall of Baby Doc in 1986 – in constant terror that she or her children would be targeted again. Each day, the children rushed straight home from school and didn’t leave the house again. Each summer as soon as school ended, she packed them off to the countryside to breathe a sigh of relief.

Under Baby Doc, the most spectacular violence, the murdering of whole families, mass purges of the military and especially violence targeting Haiti’s wealthy families abated. But the intimate terror the Duvalier regime exercised over every aspect of daily life continued.

In Martissant, as in most Port au Prince neighborhoods, there were active members of the Macoutes in every other home. With almost unlimited power, they spied on and policed their neighbors, attacking, arresting, even killing people for such infractions as wearing an Afro, not wearing shoes or leaving a light on after dark. Since the Macoutes were not formally paid, and since the economy was in a free fall, they enacted daily violence and extortion on the population to survive.

The children of those taken in Martissant that day in 1968 never forgot what happened to their fathers. As soon as they were old enough – just kids really, 12, 13 years old – they found themselves drawn into, and then propelling forward, a movement for change. Each Sunday morning, a chain of young people from Martissant set off across the city, jen pase pran jen, young people gathering more young people, until they numbered in the hundreds, arriving at the doors of St. Jean Bosco in La Saline, where a young priest was saying out loud what they had been saying in their hearts all their lives: Fok sa Chanje. This must change. These young people, joined by thousands of others in church and grassroots organizations across the country, ignited a movement that, after long struggle and many lost lives, finally overthrew a 30-year dictatorship.

For the veterans of this struggle to have to watch Jean Claude Duvalier return a free man to the scene of his crimes now – on the heels of the one-year anniversary of the earthquake, after losing 300,000 countrymen; while a cholera epidemic rages, having already taken 4,000 lives; while a U.N. military mission occupies the country, at a cost of over $500 million a year, while the U.N. cannot even raise a third of that to fight the cholera that its troops brought to the country in the first place; while more than a million people live in the streets of Port au Prince under nothing more than shredded tarps; after an “election” that was an insult to democracy, excluding Fanmi Lavalas, Haiti’s largest political party, drawing less that 25 percent of eligible voters, and riddled with fraud and irregularities even for the limited voting that did take place; and while Haiti’s twice democratically-elected former President Jean-Bertrand Aristide is in forced exile in South Africa – under these circumstances watching Duvalier return was excruciating.

The fact that Duvalier himself appears ill and rather feeble is no great comfort. The fact that he was questioned by prosecutors on Tuesday and then released back to his luxury hotel, while far better than nothing, is still not reassuring. The presence of Jodel Chamblain, the founder of the notorious death squad FRAPH, which terrorized Haiti from 1991-1994, at Duvalier’s side as he went to court was flat out terrifying. The traumatizing symbolism of Duvalier’s return at Haiti’s weakest hour is an insult to the dead and an assault on the living.

If the response of Haitians to Duvalier’s return has so far been muted, it is in part because people are still in shock. This has been a week of intense resurgent memory, private at first, but more and more communal, as people gather to recount and retell, as parents share new details with their children, as the radio waves fill with the voices of survivors. By week’s end the flood of memory was transformed into the first half dozen of what will likely be a flood of formal legal complaints against Duvalier for torture, forced exile, rape and murder.

All week rumors flew that Aristide was on his way – will come Tuesday or Thursday or next week – and this offset some of the anger. Last Thursday, the teledyol (rumor) had it that CNN was reporting Aristide had purchased a one-way ticket home. Hearing this, willing it to be true, some Haitians, began making painful concessions in their heads. One former parishioner of St. Jean Bosco put it this way: “OK, Duvalier, he’s old, he’s dying. We’ll stomach him, if that’s what it takes to bring Aristide back.”

On Sunday, Jan. 23, The Miami Herald ran a full-page letter sponsored by the Haiti Action Committee in California echoing the call of Haitians for the return of Jean Bertrand Aristide from exile. The statement is signed by politicians, activists and other prominent figures, including Dr. Paul Farmer, founder of Partners in Health, Danny Glover, actor and activist, and Rev. Jesse Jackson.

What does the U.S. government say?

Regarding Duvalier, “This is a matter for the government of Haiti and the people of Haiti,” said State Department spokesman P.J. Crowley.

Regarding Aristide, “Today Haiti needs to focus on its future, not its past,” Crowley said.

In case there were lingering doubts about who is preventing Aristide’s return.

The U.S. government is always quick to urge others to forget the past. But memory is long, bodies bear scars, the murdered father gives birth to the lifelong militant and the coup d’etat of 2004 is not even the past.

As long as Aristide is in exile, that coup remains an open wound. The divisions the State Department is so concerned Aristide will somehow seed are there in plain view for everyone to see. Have and Have not. Moun Anba Tant, Moun Nan Kay. The people living under tents, the people who have homes.

The earthquake, and especially the disastrous international response, seem only to be further entrenching the chasm between rich and poor. Aristide didn’t create this chasm, nor can his return transform it in a day. But his presence would be a sign of hope to Haiti’s poor, who’ve had precious little of that in the last year.

“Build back better,” Bill Clinton said last year. A house built on impunity and exclusion will fall again. The rubble must be cleared first. Let Duvalier face justice for his crimes. Stop trying to hobble together a government from an election that everyone knows was a sham. Let all parties participate; let the Haitian people vote freely. And let Aristide come home again.

Laura Flynn, a writer, activist and board member of the Aristide Foundation for Democracy, is the editor of “Eyes of the Heart: Seeking a Path for the Poor in the Age of Globalization“ by Jean-Bertrand Aristide. This story first appeared in the Huffington Post.

Remembering Haitian Creole pigs

by Jean Bertrand Aristide

Store

Store