by Mumia Abu-Jamal

The name Amiri Baraka has been known to me since my teens, when I was a member of the Black Panther Party.

His name was often linked with that of Dr. Maulana Karenga, credited with founding Kwanzaa, of the L.A.-based US Organization, which began as competition with the L.A. Black Panthers for influence in Black L.A., and devolved into a deadly feud between enemies, aided and abetted by the maliciousness of the FBI.

His name was often linked with that of Dr. Maulana Karenga, credited with founding Kwanzaa, of the L.A.-based US Organization, which began as competition with the L.A. Black Panthers for influence in Black L.A., and devolved into a deadly feud between enemies, aided and abetted by the maliciousness of the FBI.

But Baraka posed an intriguing figure, for he radiated both love and rage, funneled through his poems, which pulsated with revolutionary fire.

He was born in 1934 in Newark, N.J., as Everett LeRoy Jones and become a rising star of the Beat era in the East Village of New York.

When he joined the U.S. Air Force, he found a revelation in books while traveling in Chicago. He saw a bookstore with a green door – called The Green Door – and within he had an epiphany. In his 1984 autobiography, he wrote:

“Something dawned on me, like a big light bulb over my noggin. The comic strip idea lit up my mind at that moment as I stared at the books. I suddenly understood that I didn’t know a hell of a lot about anything. What it was that seemed to me then was that learning was important. I’d never thought that before” (Pages 343-344).

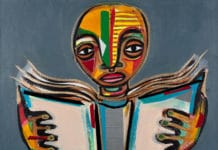

That moment spurred him on to seriously read, study and enlarge his understanding, not for a grade but for the simple “joy” of learning.

He gorged himself on books. On all kinds of subjects: poetry, history, statistics – and beyond.

He gorged himself on books. On all kinds of subjects: poetry, history, statistics – and beyond.

In July 1960, he would hit another “turning point.” He went to Cuba. In his 1966 essay, “Cuba Libre,” he recounts his reaction to harsh criticism of the U.S. Empire, saying, “I’m a poet … what can I do? I write, that’s all. I’m not even interested in politics.”

A Mexican poet, Jaime Shelley, responded acidly: “You want to cultivate your soul? In the ugliness you live in, you want to cultivate your soul? Well, we’ve got millions of starving people to feed, and that moves me enough to make poems out of.”

That trip radicalized him and his poetry and spurred him on to Black cultural nationalism, revolutionary nationalism, Marxism and the building of Black community organizations.

The impacts of learning and Cuba kept him seeking the correct synthesis of revolutionary politics to transform society.

Although lesser known, he was a music critic of considerable insight. His love of jazz was deep, even spiritual. But he also loved R&B (rhythm and blues), gospels and blues, as cultural expressions of various stages of Black life.

He also dug rap, it being, at bottom, poetry; but he condemned the corporate control over its production and distribution.

He also dug rap, it being, at bottom, poetry; but he condemned the corporate control over its production and distribution.

Of rap, he wrote:

“That’s why Rap delighted me so and still does (even though now it’s been widely co-opted by Uncle Bubba and the Mind Bandits) because I could see that some of what came out of us had taken root. An open popular mass-based poetry. It arrived, that’s why the corporations moved so swiftly to “cover” and coopt. Why the disappeared Grand Master Flash and Afrika Bambaata, accused Prof. Griff of the Big A-S and brought in fresh rap like Two Live Crew. Gangsta rap was also brought in to exchange political agitation with ignorant braggadocio and thuggish imbecility, justifying the state nigger-you annihilation program” (Page 502).

Amiri Baraka and his wife, Amina, were good friends of MOVE’s Pam Africa and spent time together when she was in Newark.

But Baraka put his best self in his poems, which revealed his wit and his anger. In his 1979 poem “In the Tradition,” he has a line that said it all: nigger music’s about all / you got, and you find it / much too hot.

Amiri Baraka was 79.

© Copyright 2013 Mumia Abu-Jamal. Read Mumia’s latest book, “The Classroom and the Cell: Conversations on Black Life in America,” co-authored by Columbia University professor Marc Lamont Hill, available from Third World Press, TWPBooks.com. Keep updated at www.freemumia.com. For Mumia’s commentaries, visit www.prisonradio.org. For recent interviews with Mumia, visit www.blockreportradio.com. Encourage the media to publish and broadcast Mumia’s commentaries and interviews. Send our brotha some love and light: Mumia Abu-Jamal, AM 8335, SCI-Mahanoy, 301 Morea Road, Frackville, PA 17932.

Store

Store