by Dennis Boatwright

The increase in hunger strikes in state prisons throughout the United States, which have been inspired by the courageous examples of Ohio and California prisoners, have garnered sympathetic media coverage from non-mainstream news sources. Leading this honorable group is the San Francisco Bay View, The Michigan Citizen, The Voice of Detroit and the up-and-coming The BottomLine. The hunger strikers’ actions present an ideal moment to reflect upon and examine and, some argue, re-examine the overall tactics prisoners choose to resist state-sponsored brutality and inhumane treatment.

The increase in hunger strikes in state prisons throughout the United States, which have been inspired by the courageous examples of Ohio and California prisoners, have garnered sympathetic media coverage from non-mainstream news sources. Leading this honorable group is the San Francisco Bay View, The Michigan Citizen, The Voice of Detroit and the up-and-coming The BottomLine. The hunger strikers’ actions present an ideal moment to reflect upon and examine and, some argue, re-examine the overall tactics prisoners choose to resist state-sponsored brutality and inhumane treatment.

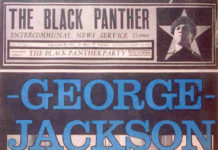

A critical examination is overdue for the simple fact that with the exception of written pieces presenting historical analysis and victimization accounts, no new seminal prison literature has been produced that is both thought-absorbing as well as strategy focused. I confidently support this assertion based upon existing publications. For instance, “Blood in My Eye,” “Soledad Brother” and “The Wretched of the Earth” are still the primary – and perhaps only – liberating tracts introduced to newer generations of inmates searching for enlightenment and a better understanding of their own incarceration.

This statement does not imply that the insights offered by these books are obsolete or irrelevant to current conditions and challenges inmates face. In fact, they are timeless classics that all prisoners should have copies of in their personal libraries.

But a growing number of new arrivals are inquiring about the political forces and socioeconomic conditions that strongly influence the decisions of urban teens to commit crimes. Many of the books we read way back at the beginning of our bits may not sufficiently cover the unique questions they ask or appeal to certain ideological preferences they hold. Moreover, two generations have passed since the publication of these pioneering books.

In the last four-plus decades, the form of oppression confronting today’s inmates has multiplied and changed its usual appearance, resulting in confusion, frustration and desperate reactions. While the form and application of oppression continues to appear in ever-new expressions, we have not upgraded our methods and strategies to deal effectively with these changes.

The absence of new literature, to a large extent, lies on the shoulders of those of us who have been at the forefront of the prison resistance movement for the last 15-20 years. Since 1989, this writer has been locked up in maximum, close custody, medium, and now minimum security prisons. Such a prolonged, varied imprisonment has enriched my understanding of how inmates respond to and cope with critical situations.

Not surprising, the security level that prisoners are held in determines how and to what degree they respond to injustice and staff provocations. In addition, the consciousness-building activities I’ve been engaged in fated me to meet some of the brightest minds and strongest characters.

Prominent among them are Imam Siddique Adbullah Hasan (Ohio), Lacino Hamilton (Detroit), Bomani Shakur (Ohio), Scott Libby (Detroit), James L. Howard (Michigan), T’chaka Olugala Shabazz (Indiana), Richard Wembe Johnson (California) and Kwame Kzeguire (New Jersey). All of us in our own ways have resisted departments of corrections’ attempts to make us tolerant of their excesses and indifferent towards the mistreatment of fellow prisoners. Our steadfastness, however, comes with harrowing consequences, which we have learned to handle with unparalleled composure and dignity.

Because we have not betrayed our integrity or moral fortitude, we have been placed either on death row or held in other forms of severe solitary confinement – not unlike Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X, Nelson Mandela, Patrice Lumumba and Bobby Sands, to name just a few. It comes with the territory.

Nevertheless, in spite of the ceaseless privations and mental trepidations we have to endure, it is past time for us to raise our learning curves to enable us to broaden and deepen the discourse we have amongst one another. Not so much in a sense of consuming a larger quantity of the same genre of material, but in a sense of elevating our subject matter to new heights.

Up to our time, we have had many exemplary martyrs and revolutionaries to gain inspiration from; but we have had very few soldier-scholars or statesmen whose thoughts could present innovative strategies to advance our interests. That is, we have had numerous prison versions of the great military commander Vo Nguyen Gisp, but very few versions of Deng Xiaoping, a far-looking person who is today lauded for setting China on a track to become a global economic power and, by extension, a formidable military power.

Continuing this analogy, prisons have had their versions of Che Gueverra but virtually no Dr. Ronald Walters, John Lewis Gaddie, Sheikh Hasan Masrullah or George Kennan. The latter international relations scholar wrote “The Sources of Soviet Conduct,” a pioneering 1947 foreign affairs article that proposed a theoretical military paradigm on how the U.S. can effectively engage the former Soviet Union in the Cold War. Keenan’s insights guided U.S. policies up to the break-up of the former Soviet Union, and it is this type of reflective thinkers that are needed in the prison system.

The call for statesmen-like prisoners is not meant to downplay the indispensable role of ultra-militants because there is always a need for more. In fact, this article is meant to convey that, in addition to cultivating soldiers and intellectuals, we need to structure our studies to facilitate the growth of statesmen – or, using Plato’s words, philosopher kings. Incarcerated individuals who grasp the sciences of human interaction can utilize their expertise to outline strategies and create concepts that will make our struggle a balanced blend of militancy and intellectualism.

This objective requires us, at a minimum, to incorporate the broad disciplines of political science, economics and psychology. We must study these fields systematically, in a curriculum format, even if it be entirely through self-learning.

This does not mean scrap your current study material. It means, in addition to reading Na’im Akbar’s “Breaking the Chains of Psychological Slavery,” read Erich Fromm’s “Anatomy of Human Destructiveness.” After reading Staughton Lynd’s “Lucasville,” read Henry Kissinger’s “Diplomacy” or “On China.” Likewise, if you have read Claude Anderson’s “Black Labor, White Wealth,” now pick up political economist Joseph Schumpeter’s “Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy.” And for a current analysis of how politics affect resource distribution, it is greatly recommended you read material written by Joseph E. Stiglitz or Paul Krugman.

Although these recommended books were not written with prison liberation in mind, the knowledge they offer is invaluable. You see, economists like Joseph E. Stiglitz and Julianne Malveux could point out that, despite the recession we’re in, there are plenty of jobs available. The problem is that Americans are only qualified for half of them. Thus, many U.S. corporations must import qualified individuals from China and India who possess the requisite knowledge and skill sets to fill these $75,000-$150,000 a year positions.

To be fair, the prison movement is showing signs of intellectual growth and emotional maturity. Bright lights are starting to flicker, particularly in California.

For example, Heshima Denham and other brothers detained in the infamous SHU at Corcoran, started NARN Collective Think Tank (NCTT). Their initiative needs to be replicated at every correctional facility.

Pivoting off this point, a couple of years ago this writer founded two think tanks to help facilitate higher thinking among prisoners. They are 1) the Center for Corrections Studies (CCS) and 2) the Center for Pan-African Studies (CPAS). The names of these two organizations reflect their focus. They are hosted by an online newspaper, The BottomLine at www.NoFrillNews.com., which is published by this writer. In addition, a forthcoming book, written by this author in collaboration with Imam Siddique Abdhullah Hasan, elaborates on the above issues from a statesman’s perspective.

This article is deliberately thin on offering solutions because of the limited aim of this piece. But below are some points we can build on for the time being.

The prison movement needs to create allies and linkages with people or organizations who may be part of mainstream establishment, but privately sympathetic to our cause. Individuals like Reps. Barbara Lee and John Conyers come to mind. Although such individuals are a part of the establishment, they can be of immense help to the prison liberation movement. How to get them to assist us is an entirely different matter, but campaign contributions is a good start. We can, however, begin from here:

· Establish a base through which prisoner-statesmen have smooth communication channels to discuss strategies and exchange ideas.

· Create coffers (war chest) to finance objectives.

· Start a privately-funded PAC (political action committee) to coordinate the activities of resisters and think tanks so that our efforts won’t be wasted by overlapping or needless repetition, which wastes funds. Furthermore, this PAC can vet out bogus causes to ensure that precious funds won’t be wasted on misleading political prisoner persecution claims.

· Hire professional lobbyists.

· Be flexible and self-critical of one’s own issues and actions.

The above are just a few ideas inmates and outside supporters can consider and discuss. The suggested measures will enable us to advance our cause while resisting our oppressors on multiple fronts. Better organization and efficient use of our human capital will increase the chances our efforts and sacrifices will achieve their objectives. When the above political structures are formulated, they can only enhance the efforts of hunger strikers and other acts of resistance.

True, we don’t fear death or persecution, but minimizing losses is a part of wise strategy. We struggle to win. Unnecessarily losing some of our best minds to indeterminate isolation won’t help this purpose.

Send our brother some love and light: Dennis Boatwright, 206715, Carson City Correctional Facility, 10247 Boyer Road, Carson City, NV 48811.

Store

Store