by Ira Glasser

The story begins nearly 40 years ago. At that time, it was unthinkable, literally, to imagine a day when a Black man might be elected president. Indeed, in some parts of the country, it was still dangerous for a Black man to vote or organize against the oppressive system of racial subjugation that still prevailed despite the recent legal victories of the civil rights movement. And in 1968, both Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy were assassinated.

In the states of the Deep South, it was not uncommon for invented criminal charges to be brought against civil rights advocates during the civil rights movement as a way of suppressing their political activities. And in the North, the emergence of the Black Panthers, an organization of aggressive tactics and militant language, frightened many whites. Brandishing guns and the rhetoric of violence, they provided an easy excuse for law enforcement to go after them.

No civil rights advocates defended actual crimes that may have been committed. But in many cases, evidence was manufactured and guns planted by law enforcement officials anxious to break the back of this increasingly militant movement. In Chicago, the FBI broke into a Black Panther apartment and slaughtered its occupants. And in New York, Black Panthers were brought to trial upon evidence that ultimately could not survive scrutiny. In one case, a Black man was shot down by cops and then, as he lay dying, charged with attempted murder of the police who shot him, on the basis of a gun in his coat pocket that later was proved to have been planted by the police officer.

In this context, Herman Wallace and Albert Woodfox were arrested in Louisiana, convicted of separate crimes and sent to the Louisiana State Penitentiary, an 18,000 acre former slave plantation known as Angola. In those days, most Southern prisons were racially segregated, and many were unspeakably brutal. During the early 1970s, when Wallace and Woodfox first were sentenced to Angola, it was known – even according to the Louisiana State Department of Corrections’ official history – as the “bloodiest prison in the South.”

It is hard to imagine today what Angola was like then, but it is important to understand the circumstances that led to what happened to Wallace and Woodfox and to what I have called their crucifixion unto this day.

Angola was awash in violence and over-run by inmate gangs, encouraged and enabled by prison officials as a way of maintaining control. A gruesome system of sexual slavery prevailed, where new prisoners were openly bought and sold into submission; this system was sanctioned and facilitated by guards, as Warden C. Murray Henderson admitted in his book.

Favored inmates were given state-issued weapons and ordered to enforce this system of sexual slavery. Between 1972 and 1975 alone, this armed inmate guard system claimed the lives of 40 prisoners and seriously maimed 350 more. For those who survived, there was a 96-hour work week, harvesting crops of soybeans, cotton, corn and wheat at a minimum wage of 2 cents an hour. This was the prison Herman Wallace and Albert Woodfox came to in the early ‘70s.

Inspired by the civil rights movement, Wallace and Woodfox began a Black Panther chapter in the prison. They couldn’t do much except talk, but talk they did, to as many of the inmates as they could, about human dignity and self-respect and the need to work to protect vulnerable inmates from being pressed into sexual servitude. This did not endear them to the administration – free speech had not yet come to prisons – nor to the guards and the inmates who functioned as enforcers. But they persisted, and their talk became a thorn in the side of the men who ran the prison.

Then, on April 17, 1972, a young prison guard, Brent Miller, was found stabbed to death in a prison dormitory. He was 23, and his widow was 17.

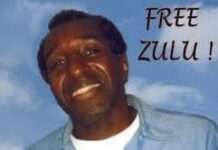

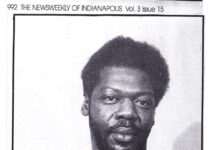

Wallace and Woodfox were immediately put into solitary confinement, little more than a 6 by 9 cage, despite no evidence connecting them to the crime. They would remain there for the next 36 years, and they are there now, as this is written – in an even smaller cell, 23 hours a day, no yard time, no telephone calls (except to their lawyers) and no contact visits.

No physical evidence ever connected them to the crime. A bloody fingerprint found at the murder scene did not match either man, and both men had multiple alibi witnesses, who were ignored. Moreover, prison officials refused to check those fingerprints against the fingerprint database, and they have continued to refuse to this day. Somebody made that bloody fingerprint, but it wasn’t Woodfox or Wallace. Yet they were charged with the crime.

Other prisoners who testified against them later recanted and said they were coerced by prison officials to lie under oath.

The only evidence left against them is the unreliable testimony of a convicted serial rapist named Hezekiah Brown, who had previously been on death row and who was subsequent to his testimony given a variety of special privileges and later pardoned by the governor, after the warden had personally lobbied for his release. Although this was not revealed at the time, Warden Henderson years later testified, at Woodfox’s re-trial, that he had made an agreement with Brown: He would help obtain a pardon if Brown would help “crack the case.”

Before the pardon, Brown was granted special privileges: As Warden Frank Blackburn wrote in a letter to the Secretary of Corrections, “This, I feel, would partially fulfill commitments made to [Brown] in the past with respect to his testimony in the state’s behalf in the Brent Miller murder case.” The Secretary of Corrections replied: “I concur. Warden Henderson made the original agreement with Brown … I think we should honor the agreement.”

It is pretty clear that, as often happened in those days to vulnerable Black activists, Wallace and Woodfox were pilloried and punished for their political activities in behalf of prison reform and railroaded into a cage for the next 36 years.

About 10 years ago, a small group came together to try to overturn this injustice. Their numbers have grown and progress has been made as the facts have slowly but systematically been brought before independent courts.

In 2006, a state magistrate, after an extensive review of Herman Wallace’s case, recommended that his conviction be overturned. But by a 2-1 vote, the state appeals court decided to keep the conviction in place. That decision is now pending appeal in the Louisiana State Supreme Court.

In Albert Woodfox’s case, a federal magistrate reviewed the evidence thoroughly and recommended his release. A federal district court judge, James Brady, upheld her recommendation, overturned the conviction and granted bail pending the state’s decision about whether to appeal or re-try him. The state appealed to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which reversed the grant of bail pending appeal.

So the court cases grind slowly, as court cases do.

But the brutality that long ago ignited this injustice continues in Louisiana, to a nearly unimaginable degree. When Woodfox was initially granted bail, a niece of his and her family agreed to take him in. Louisiana Attorney General Buddy Caldwell then embarked upon a public scare campaign reminiscent of the kind of inflammatory hysteria that once was used to provoke lynch mobs. He called Woodfox a dangerous rapist, even though he had never been charged, let alone convicted, of rape; he sent emails to neighbors calling Woodfox a convicted murderer and violent rapist; and neighbors were urged to sign petitions opposing his release. In the end, his niece and family were sufficiently frightened and threatened that Woodfox rejected the plan to live with them while on bail. All of this took place while the appeals court was considering the state’s appeal of the grant of bail.

Angola Warden Burl Cain was even more revealing. During the bail hearing, he testified as to why Woodfox should not be granted bail, and why he needed to be kept in a cage and away from other inmates. Here are a few excerpts:

“The thing about him is he wants to demonstrate. He wants to organize. … A hunger strike is really, really bad, because you could see he admitted that he was organizing a peaceful demonstration. … He is still trying to practice Black Pantherism, and I still would not want him walking around my prison because he would organize the young new inmates.”

For Attorney General Caldwell and Warden Cain, it is still 40 years ago, and they can only respond to aspirations for justice by putting its advocates in the hole. Evidence is irrelevant or to be manufactured to achieve the ends of repression.

Perhaps more surprising, and for that reason even more reprehensible, is the immorality of Gov. Bobby Jindal. Elected on a platform of reform and widely touted as the kind of fresh face for the Republicans nationally that Obama has been for the Democrats, Jindal could stop these crude injustices. But he continues to back them, staining himself and his state with his defense of the indefensible.

By now, anyone who has looked fairly and independently at the evidence in this case has concluded that the convictions were unsupportable. Even Brent Miller’s widow now believes Wallace and Woodfox were wrongly convicted, and she would like the state to find out who killed her husband that April day in 1972.

But the habits of the old South die hard and the courts move slowly. A Black man will be inaugurated on Jan. 20. But Albert Woodfox is 61 and Herman Wallace 67. They will not see that inauguration, nor benefit from it. It is Christmas Day, and they are about to begin their 37th year in the dungeon of the old slave plantation. A crucifixion.

Where is the public outrage that will resurrect them?

Until his retirement in 2001, Ira Glasser was executive director of the ACLU, where he began working in 1967. This commentary first appeared Christmas Day 2008 in his blog on Huffington Post. To learn more, visit www.Angola3.org, www.3blackpanthers.org and www.A3grassroots.org.

Store

Store