Testimony of Margaret Winter, associate director of the ACLU National Prison Project, at the California Senate and Assembly Public Safety Committees’ Joint Informational Hearing on Segregation Policies in California’s Prisons Oct. 9, 2013 (Ms. Winter’s testimony begins at one hour, 18 minutes – 01:18) :

In my work with the ACLU over the last 20 years, I have investigated, monitored and brought class action litigation on conditions of confinement in prison and jail systems around the country. I have testified as an expert to the Prison Rape Elimination Commission, to the Committee on Safety and Abuse in American Prisons, to the Citizens Committee on Violence in the Los Angeles City Jails and I was recently invited by the president of the American Correctional Association to speak at the ACA’s National Conference on Solitary Confinement.

I have been asked by this committee to give an overview of solitary confinement nationally and recent developments as to what other jurisdictions are doing today to address the issue of solitary confinement.

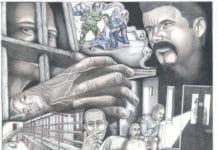

It is well known that the U.S. has the largest incarcerated population in the world, with 2.2 million people behind bars on any given day, and that we have the world’s highest per capita incarceration rate too, a rate that is five to 10 times higher than any Western democracies like Canada, the U.K., Germany and France. But what is less well known is that the U.S. has more prisoners in solitary confinement than any other nation. It is estimated that on any given day there are 80,000 in the U.S. held in solitary confinement.

The U.S. has more prisoners in solitary confinement than any other nation. It is estimated that on any given day there are 80,000 in the U.S. held in solitary confinement.

Human beings are social animals. Being subjected to prolonged social isolation causes extreme psychic punishment and pain. And especially when that isolation is combined with enforced idleness and sensory deprivation – it causes agonizing psychic pain. And over time in solitary confinement, those who start out sane often develop mental illness. Those who start out ill are likely to become more seriously ill.

It is well known that a very, very big and significant portion of the prison population in California and nationwide is mentally ill to begin with. Some never recover from the effects of solitary confinement; they go round the bend, so to speak, irretrievably so that they don’t come back.

All of this has been known for a very long time. In 1890, the U.S. Court described the effects of solitary confinement like this: “A considerable number of the prisoners fell, after even a short confinement, into a semi- fatuous condition, from which it was next to impossible to arouse them, and others became violently insane; others still, committed suicide; while those who stood the ordeal better were not generally reformed, and in most cases did not recover sufficient mental activity to be of any subsequent service to the community.” (In Re Medley, 134 US 160, 168.)

Virtually every reputable study of the effects of solitary confinement lasting more than 60 days has found evidence of its negative psychological effects.

Prisoners with seriously mental illness are particularly at risk. And almost every federal court to consider the issue has ruled that subjecting prisoners with serious mental illness or developmental disabilities to isolation violates the Eighth Amendment.

Human beings are social animals. Being subjected to prolonged social isolation causes extreme psychic punishment and pain. And especially when that isolation is combined with enforced idleness and sensory deprivation – it causes agonizing psychic pain.

Teenagers, young people are also at greatly heightened risk. Most suicides in juvenile corrections facilities occur in solitary confinement. And, in fact, there is adequate evidence to say that solitary confinement causes suicide. In the California system, the evidence is that 60 to 70 percent of successful suicides in prisons occur in solitary confinement.

Expansion of solitary confinement

So with all of this accumulated knowledge, why do we have 80,000 people every day in the United States in solitary confinement? What happened since 1890? Or since the mid-19th century when all of this became well known?

What happened was in the mid to late 1990s there was a mania for so-called SuperMax prisons, that is prisons entirely dedicated to long term solitary confinement. This mania swept the country. This was at a time of acute public anxiety about crime.

SuperMax prisons, like draconian sentences and three strikes laws, came into political fashion. It was like a statement that the state was “tough on crime.” There was a SuperMax building boom and, by 2006, more than 40 states, as well as the federal government had at least one SuperMax prison.

In the last few years a national dialogue has opened up strongly questioning the utility and justification for solitary confinement.

Everyone agrees that some prisoners may need to be physically separated for some period of time to prevent them from hurting others. But even when there is a demonstrable compelling need, a security need for physical separation, the issue is whether there is ever, EVER justification for prolonged and extreme social isolation, sensory deprivation and enforced idleness.

There is a growing body of evidence that solitary confinement does little or nothing to promote public safety or prison safety. And that it is so harsh and so likely to damage people that is should be used as sparingly as possible. Only, ONLY for prisoners who pose a current, active, on-going serious threat to the safety of prison staff and other prisoners. It should be used only as a last resort and for as short a time as possible.

The evidence that solitary confinement is not only harmful but unnecessary and incredibly costly has given rise to a rapidly expanding nationwide reform movement. The reform movement has been fueled in part by the financial crisis. The states are facing crushing budget deficits and spending for education, public health care, and other basic public social services are being slashed to the bone.

Solitary confinement does little or nothing to promote public safety or prison safety. It is not only harmful but unnecessary and incredibly costly.

A serious national debate has already opened up as to whether the staggeringly high cost of solitary confinement is justifiable. Incarceration is expensive. Solitary confinement is by the far the most expensive form of incarceration. The daily per prisoner cost at the Federal Bureau of Prisons highest security SuperMax is $80,000 a year, triple the cost in a non-SuperMax high security facility. The per prisoner cost in Illinois’s recently closed Tamms SuperMax was more than $60,000 per year, triple the state’s average per prisoner cost.

Furthermore, there is little or no evidence that solitary confinement actually promotes either public safety or prison safety. A 2006 study on the effect of opening SuperMax prisons in Arizona, Illinois and Minnesota found that the SuperMax had either little or no effect on reducing violence or that it was actually associated with increased violence.

A 2007 study by the Mississippi Department of Corrections showed that violence levels plummeted by 70 percent of previous levels when the commissioner of the Mississippi Department of Corrections reduced the number of prisoners held in solitary confinement by 85 percent. That is, the level of violence declined in almost direct proportion to the radical reduction of solitary.

A reduction in the number of prisoners in segregation of prisoners in Michigan also has resulted in a decline in violence and other misconduct. And furthermore we cannot forget that prisoners who were held in solitary have higher recidivism rates than comparable prisoners who were not held in solitary.

Mississippi

I want to talk to you about Mississippi. Mississippi is the reddest of the red states. Mississippi was the unlikely trailblazer in radically reducing the use of solitary confinement.

Violence levels plummeted by 70 percent of previous levels when the commissioner of the Mississippi Department of Corrections reduced the number of prisoners held in solitary confinement by 85 percent.

In 2004, the ACLU won a lawsuit challenging the horrific conditions on Mississippi’s death row, which was situated in a corner of Mississippi’s SuperMax unit, a 1,000-bed facility known as Unit 32. Mississippi has a prison population of about 20,000 prisoners, 1,000 of them in SuperMax.

Mississippi’s commissioner had long insisted that solitary confinement was necessary for these 1,000 men because they were “the worst of the worst” violent gang members, and there was no other way to keep the prison and public safe.

But in 2007, after further litigation, something remarkable happened: Mississippi’s commissioner agreed to work with a national classification expert from the NIC (National Institute of Corrections), an arm of the Department of Justice that provides technical support to state prison systems, and together with the ACLU’s mental health expert and with this NIC national classification expert.

The prison officials sat down with the deputy commissioner, the head of the prisoner classification team, with the prison’s mental health team; they sat down and over the course of a few weeks, they individually considered every single one of those 1,000 cases. They applied evidence based risk assessment tools, which the NIC has developed and which have been tested many times. Applying these evidence based risk assessment tools and factors, they decided after careful review, the Mississippi officials decided that at least 85 percent of these 1,000 men in the SuperMax did not need to be isolated. They should not be isolated.

Hundreds of them had serious mental health problems and needed to be diverted to a facility where they could get intensive mental health treatment. Hundreds more were in solitary merely because they were members of gangs or simply because they had violated many, many rules, they had a history of rule infractions, many of them in response to intolerably harsh conditions, some of them acting out because they had behavior problems. But in any event, these men were not actually so dangerous to others as to need to be kept in solitary confinement.

Within a matter of months the department had actually reduced its SuperMax population by 85 percent, from 1,000 men to 150. And the result of this reduction was equally dramatic. The level of violence in the prison plummeted to a small fraction of its former level. And these figures were later documented in a study by the deputy commissioner of corrections and the NIC and the other people involved in this experiment.

Mississippi’s commissioner had long insisted that solitary confinement was necessary for these 1,000 men because they were “the worst of the worst” violent gang members. Within a matter of months the department had actually reduced its SuperMax population by 85 percent, from 1,000 men to 150. The level of violence in the prison plummeted to a small fraction of its former level.

I will never forget visiting Unit 32 in November 2007 and witnessing the transformation of a prison. I could hardly believe my eyes. This vast prison yard that had always been so silent and empty was now filled with hundreds of men, peacefully playing basketball together in newly created basketball courts, walking together to classrooms that had not previously existed and going to a chow hall that had never existed before because they had never left their cells. This was a successful experiment.

Three years later, in 2010, the Mississippi Department of Corrections permanently shuttered Unit 32 and reduced the number of prisoners in solitary confinement, throughout the state, to a small fraction of what it had been. The state, in the process, saved millions in operating costs, and that is a big deal in Mississippi, which is one of the very poorest states. Mississippi Corrections Commissioner Christopher Epps has used that experience to become a national spokesperson against the over use of solitary confinement, and as the current president of the American Corrections Association, Commissioner Epps has encouraged corrections officials nationwide to embrace reform.

Solitary confinement reduction spreads

Other states have followed in Mississippi’s path, including states with some of the largest prison populations in the nation. In 2008 New York passed the SHU Exclusion Act, a law that diverts prisoners with serious mental illness away from isolation and into mental health treatment units.

In 2010, Maine Department of Corrections – Maine had an exceedingly harsh isolation policy. Maine reversed course voluntarily and made isolation a last resort rather than a default practice. And over the course of 18 months, the state reduced its solitary confinement population by 50 percent. At the end of 2012 the trend continued.

Illinois permanently closed Tamms Correctional Center, the state’s only SuperMax prison. In 2013 Colorado closed a 316 bed SuperMax unit after cutting its solitary population by one third.

Mississippi Corrections Commissioner Christopher Epps has used that experience to become a national spokesperson against the over use of solitary confinement, and as the current president of the American Corrections Association, Commissioner Epps has encouraged corrections officials nationwide to embrace reform.

In the last few years, there has been a surge in state legislative activity to limit the use of solitary confinement. In 2013 bills were proposed to limit or ban the use of solitary confinement of juveniles in California, Florida, Montana, Nevada and Texas. Nevada actually enacted a bill that places restrictions on the use of isolation of youth in juvenile facilities.

A similar bill on juvenile solitary confinement practices was introduced in Texas. And Texas passed a law requiring correctional facilities to review and report on their use of isolation.

Maine, Colorado and New Mexico have each passed bills mandating studies on the use, impact and effectiveness of solitary confinement. And this is an incredibly powerful and important component of addressing the problem, of actually getting the data. Because most states don’t have it yet.

A Massachusetts bill would require a hearing within 15 days of placement in segregation, limit segregation to no longer than six months, except in exceptional circumstances, and provide for access to programing to prisoners in segregation.

In the last few years, there has been a surge in state legislative activity to limit the use of solitary confinement.

The federal government has also recently become involved in the movement to limit solitary confinement. In June 2012, the first ever Congressional hearing on solitary confinement was held before the State Judiciary Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights and Human Rights.

In 2013 U.S. Senate passed the Border Security Economic Opportunity Security Immigration and Modernization Act, which limits the length of solitary confinement to 14 consecutive days – 14 days – unless the Department of Homeland Security determines that continued placement is justified by extreme disciplinary infraction or is the least restrictive means of protecting the other detainees. The bill also bans the use of solitary for juveniles under the age of 18, restricts the use of solitary for those with serious mental illness and for involuntary protective custody.

Also in 2013 something very important happened when the Government Accountability Office, the independent investigative agency of the U.S. Congress, undertook a comprehensive review of the use of solitary confinement by the federal Bureau of Prisons. The bureau is the nation’s largest prison system, holding about 15,000 people in solitary confinement.

In May 2013, the GAO issued a report finding that the bureau had never assessed whether solitary confinement has any effect on prison safety; that the bureau had never assessed the effects of long term segregation on prisoners; that the bureau had not adequately monitored segregated housing to insure that prisoners received food, out of cell exercise and other necessities.

And the BOP agreed to adopt the GAO’s recommendations to gather data, to assess the impact of long-term segregation on prisoners and to assess the extent to which segregation actually serves the purpose of making prison staff, inmates and the public safe.

The federal Bureau of Prisons is the nation’s largest prison system, holding about 15,000 people in solitary confinement. In May 2013, the GAO issued a report finding that the bureau had never assessed whether solitary confinement has any effect on prison safety; that the bureau had never assessed the effects of long term segregation on prisoners; that the bureau had not adequately monitored segregated housing to insure that prisoners received food, out of cell exercise and other necessities.

Another sign of the times that we are on a wave of reform is that in May 2013, the Department of Justice completed an investigation of solitary confinement in a medium security prison in Pennsylvania and found that Pennsylvania was housing prisoners with serious mental illness and developmental disabilities in solitary confinement and that this practice violated the inmates’ rights, not only under the Eighth Amendment but also under the Americans With Disabilities Act.

The Justice Department notified the governor of Pennsylvania that the DOC was going to expand its investigation into the use of isolation on prisoners with serious mental illness and intellectual disabilities into other Pennsylvania prisons.

Many major national non-governmental organizations are now involved in the challenge to solitary confinement. The National Religious Campaign Against Torture has made solitary reform a priority. In 2010, the American Bar Association revised its standards on treatment of prisoners to recommend strict limits on the use of solitary.

In 2012, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry enacted a policy opposing solitary confinement of juveniles. And also in 2012, the American Psychiatric Association approved a policy opposing the prolonged segregation of people with serious mental illness.

And now an effort is underway to amend the American Institute of Architects’ Code of Ethics to prohibit the design of facilities intended for prolonged solitary confinement.

There has been a new focus internationally against solitary confinement. In 2011, the U.N. Special Rapporteur on Torture and Terror called for a ban on solitary confinement lasting longer than 15 days, and an absolute ban on solitary confinement for youth and the mentally ill. There were similar recommendations by the Council of Europe’s Committee for the Prevention of Torture, similar in 2013 from the Inter American Commission on Human Rights.

And that commission concluded that countries should adopt strong concrete measures to eliminate the use of prolonged or indefinite isolation under all circumstances, stressing that prolonged or indefinite solitary confinement may never constitute a legitimate instrument in the hands of the state.

Six basic conclusions

There is now massive evidence to support the following six basic conclusions regarding solitary confinement:

First: Solitary confinement is so harsh and damaging that it should be used as sparingly as possible. It shouldn’t be the default. It should only be for prisoners who pose a current serious threat to the safety of others, only as a last resort and for as short a time as possible.

Solitary confinement is so harsh and damaging that it should be used as sparingly as possible. Prisoners requiring long term physical separation from others should have meaningful access to telephone calls, letters, reading materials, TV, radio and in-cell programming.

Second: Even when there is a compelling security need for physical separation, that is no justification for extreme social isolation, sensory deprivation and enforced idleness. Prisoners requiring long term physical separation from others should have meaningful access to telephone calls, letters, reading materials, TV, radio and in-cell programming. And they should have access to confidential counseling with mental health clinicians, not cell front, but confidential. They should recreate alongside of other prisoners even if they have to be confined to separate adjacent exercise yards.

Third: A prisoner should not be placed or kept in segregation without an individualized determination that physical separation is actually currently necessary for the safety of others. And that means real meaningful due process and a real meaningful review by the classification team and mental health people working together to do regular, periodic reviews.

Prisoners should not be subjected to segregation merely because they are on death row or merely because they have a life sentence or just because they are gang members. It is a question of whether their conduct, their actual conduct, in prison creates a serious ongoing threat to safety.

Fourth: Juveniles should never be kept in solitary confinement. Solitary is damaging and dangerous for juveniles.

Fifth: Prisoners with serious mental illness or developmental disabilities should never be housed in solitary. They need to be in a therapeutic environment where they can get treatment. Mental health housing can be secure without being socially isolating to people with mental illness.

Sixth, and in some ways most important: Prisoners have to be given the opportunity to earn their way out of solitary confinement by their good behavior. Above the gate to hell in “Dante’s Inferno” was written, “Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.” And that should not be the mantra of state prisons.

Prisoners have to be given the opportunity to earn their way out of solitary confinement by their good behavior.

These recommendations are not far out; they are not fringe. This is now the new. You are going to be seeing that this is the new mainstream. And California, we hope will not be bringing up the rear, but will take its place in the vanguard of adopting these recommendations and finding a roadmap toward the goal of limiting the cruel practice of solitary confinement to the least possible use.

Margaret Winter is the associate director of the ACLU National Prison Project. She was lead counsel for plaintiffs in the case that led to the closing of Mississippi’s supermax prison. She is currently challenging overcrowding, excessive force, mistreatment of the mentally ill and other unconstitutional conditions of confinement in the Los Angeles County Jail, the largest jail in the nation. Winter has successfully argued a prisoners’ rights case in the U.S. Supreme Court. She can be reached through the ACLU here, by calling (212) 549-2500 or by writing the national headquarters: ACLU, 125 Broad St., 18th Floor, New York NY 10004.

Store

Store