by Jeremy Miller

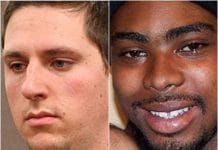

On Dec. 1, 2017, Keita “Icky” O’Neil was shot to death by former rookie police officer Christopher Samayoa, who was only four days on the job at the time of the killing. Icky was a suspect in the carjacking of a California state lottery van, a vehicle which he had just recently abandoned when he was gunned down.

Six days later, on Dec. 7, 2017, a customary SFPD townhall meeting revealed damning details, including the shooter’s own unintentionally recorded body cam footage, leading to public outcry and demands for accountability. It was underscored that Icky was unarmed at the time of his death.

A week and a half later, on Dec. 18, 2017, a civil rights wrongful death lawsuit was filed by the law offices of John L. Burris on behalf of Icky’s mother, Judy O’Neil, and in rare form, on March 9, 2018, SFPD Chief Bill Scott released – or in other words summarily fired – Christopher Samayoa for the killing.

The momentum was not to last. Just shy of two weeks after Samayoa was fired, on March 21, 2018, the SFPD would kill again – this time twenty-one-year-old Jehad Eid in the middle of a crowded local barber shop. Whatever public attention remained on Icky’s death was largely redirected to this new case, unfortunately not to return for over two years.

During this interregnum, Mama Judy’s civil case proceeded in fits and spurts with trial dates finally set in August of 2020. Then on Nov. 23, 2020, District Attorney Chesa Boudin shocked the public back to attention by filing manslaughter and related non-murder homicide charges against Samayoa for the killing, thus adding a criminal case on top of the ongoing civil case.

Fast forward to this month. The criminal process is just beginning for the manslaughter case, and on July 2, both Judy O’Neil and the City filed competing motions for summary judgement which essentially calls for a judge to rule that one side is so indisputably correct on a particular claim – or its rebuttal – as to be able to dispose of it without even bothering with a trial.

Last week, U.S. District Court Chief Magistrate Judge Joseph C. Spero published his response to the motions for summary judgement and his ruling contains serious implications both for the future of the lawsuit, as well as for public safety and the eventual (mis)carriage of justice.

The opening lines of a synopsis of Judge Spero’s July 12 ruling published in Mission Local reads: “A federal judge on Monday cleared the path for an SFPD officer who in 2017 shot Keita O’Neil, an unarmed Black carjacking suspect, to face a civil trial before a jury.”

This certainly strikes an optimistic chord if it is read uncritically. It kind of sounds like the courts are working. To wit, Eleni Balakrishnan presents a sober, rounded, well written piece of reporting on the broad strokes of Judge Spero’s decision, but its objectivity tends to mislead.

While not disputing the fact that Judge Spero’s ruling makes likely a trial on some of the claims, an alternative lead could be: On July 12, the Chief Magistrate Judge of the Northern District of California shielded both the City and the supervising officer in the killing of Keita “Icky” O’Neil from indemnity, thus implicitly supporting the politically convenient narrative of the “one bad apple.”

Strikes a different tone, doesn’t it? As regards the City, the judge ruled that there was no evidence of the killing being conditioned by or in adherence to government policy or “longstanding practice or custom.” Of course, there happened to be within the 18 months prior to Icky’s killing two high level reports, one by the DOJ and one largely by fellow judges that directly contradict such claims.

Also, it goes without saying that a popular movement which has been building for 20 years could cite dozens of analogous unaccountable slayings out of the nearly one hundred people killed by SFPD in the last two decades.

What if there were reason to believe that Officer Talusan trained his charge to be cavalier in use of force? What if Samayoa was being groomed to kill?

Moving to Edric Talusan, the supervising officer, the decision is even more consequential: Judge Spero determined that, despite the Department of Police Accountability – the dubiously named entity that was formerly known as the Office of Citizen Complaints – issuing a finding of neglect of duty on Talusan’s part for his role in the killing, and the fact that the SFPD itself demoted him from patrol and being a field training officer to inspecting commercial trucks for compliance on the basis of “failure to adequately supervise his trainee,” there was insufficient evidence to hold him liable, pointing out that: “the only basis that the plaintiff has asserted for Talusan’s liability is his failure to intervene to prevent Samayoa from shooting O’Neil.”

Judge Spero also observed: “Even if the jury can infer that Talusan reached a firm conclusion that O’Neil was unarmed at some point after he jumped from the van and into Talusan’s view, Talusan at that time would have had significantly less than one second to intervene before Samayoa fired.”

Now this sounds reasonable except for two key points. The first is that the standard for summary judgement requires that there not be a “genuine dispute as to any material fact.” There is no reason to assume that Talusan’s failure to intervene started and stopped with the brandishing and firing of Christopher Samayoa’s gun.

As a training officer with a trainee, one could stipulate many prior acts or omissions that could have led to the eventual constitutional violation which was Icky’s killing. An analogy would be an intervention in a suicide. You attempt to conduct the intervention prior to the point of the constitutional violation – the suicide – so as to preempt it.

The intervention is generally not contemplated in the few seconds before the suicidee pulls the trigger or jumps from the cliff. With this broader interpretation – which is supported by case law – many new facts appear that would at minimum warrant “genuine dispute.”

But the larger problem goes beyond Judge Spero’s legal interpretation and implicates the whole framing of events. The narrative from both parties seeks to adjudicate a failure in training. What if the theory was flipped on its head? What if instead of a failure to train, we encountered a brutal success story?

Specifically, what if there were reason to believe that Officer Talusan trained his charge to be cavalier in use of force? What if Samayoa was being groomed to kill?

Let’s look at the evidence. How is it that Talusan and Samayoa even wound up in Double Rock on the day of Icky’s killing? As it turns out, by Talusan’s own admission, he heard the service call for the carjacking and asked his sergeant for permission to respond with his trainee!

According to Talusan’s self-serving account, he “intended to meet the victim where the carjacking had occurred and take a report, which he believed would be a valuable training experience for Samayoa, who had taken few if any reports at that point and none for a carjacking.”

Allegedly, while en route to meet the victim, Talusan heard about a pursuit possibly connected to the carjacking and changed his mind, opting to go after the suspect rather than make a report.

Let’s stop there. The service call that came in was A priority, which he understood to mean, “when a vehicle is taken by force or fear.” Is it really plausible that when such a call comes in the first thought of a veteran patrolman is to run to the sergeant and say: “Hey sarge, can we go write a report?”

Secondly, Talusan claims that he decided, en route, to attempt to apprehend the suspect. If the grand training opportunity was for report writing and there were already other units following the suspect vehicle, why wouldn’t the trainer take his rookie to the victim who still needed to be debriefed about the initiating crime instead of placing an inexperienced cop into a presumably volatile and much more dangerous situation?

Next there is the question of body cameras. Neither officer had their body cameras activated during the pursuit. In addition, no dashcam or onboard vehicle recordings have been publicly released.

What this means is that if there were any tactical discussion about use of force during the pursuit, we are not privy to it. This omission of body cam activation was contrary to SFPD policy, at minimum softly suggests intent to conceal activity, and thus makes it mind boggling that we should be asked to trust the testimony of a cop facing possible civil and criminal liability that such a conversation never took place on good faith.

In neither case was there a visible weapon prior to the shooting.

Samayoa, of course, is exercising his 5th amendment right against self-incrimination due to the criminal trial, so we can’t expect a straight answer from him on this question either. Finally, Talusan’s activity immediately subsequent to Samayoa’s shooting of O’Neil is extremely suspicious.

Before we analyze this though we should take a moment to address time and history. At 10:37 a.m. on Dec. 1, 2017, Talusan can be heard on dispatch audio asking Christopher Samayoa to come with him to the car. Talusan was the driver and Samayoa the passenger.

At 10:40 a.m. a different officer reported the location of the lottery van. Before 10:42 a.m. Keita “Icky” O’Neil had already been shot. What this means is that there were approximately four minutes during which time Talusan and Samayoa could have hypothetically coordinated their approach, figured out what they were doing, and significantly less than two minutes between the initiation of active pursuit and the shot fired.

What makes this significant is that Talusan has been here before – four and a half years prior to the killing of Keita “Icky” O’Neil, Edric Talusan was involved in an OIS (officer involved shooting) that had major similarities to this case.

On March 5, 2013, while on patrol, Edric Talusan initiated a vehicle pursuit of a suspected stolen vehicle. The pursuit was also in Bayview Hunters Point. In this case, as in Icky’s case, less than two minutes after the initiation of the pursuit shots were fired.

In the 2013 case, Talusan was both the driver and the primary shooter. Unlike Icky, eighteen-year-old (at the time) Eddie Tillman survived his gunshots. In neither case was there a visible weapon prior to the shooting.

In this case, the officers involved in the shooting were exonerated from liability on the basis of a spurious claim that they feared for the life of their colleague who they believed had been run over. To hear Talusan tell it: “At that time I was – I ran up to the driver’s side window, I already had my gun pointed out. I had pointed at him telling him to stop, put his hands on the car, stop the car. And then he looked at me and then I saw the car lurch forward and then I thought that Tom [Ly] was still on the ground, so I thought the guy was going to run him over, so I discharged my firearm. I think one shot and then he kept going forward, so I fired off a couple more rounds.”

Once again it sounds like it might be reasonable until you look at the details. This shooting occurred on a cul-de-sac called George Court. Only nine seconds elapsed between the suspect turning on to George Court and being shot by Officers Talusan and Rightmire.

This means that we are supposed to believe that in nine seconds Talusan’s squad car stops, Talusan climbs over the driver’s seat to exit through the rear driver’s side door, runs around the police vehicle and, due to his anxiety about his partner getting run over, shoots Mr. Tillman but not before shouting commands that Mr. Tillman is supposed to be able to affirmatively respond to?!

The icing is that Officer Tom Ly – the supposedly run-over cop – was standing next to Talusan when he opened fire! At the time, Internal Affairs opined: “Based on watching the video multiple times, it would seem almost unbelievable that Officers Talusan and Rightmire would not have seen Officer Ly standing on the sidewalk in front of the vehicle after it had reversed, and then Officer Ly moving directly next to Officer Talusan prior to him firing.”

Despite the fact that all officers involved in the 2013 case were administratively and legally cleared of any wrongdoing, the analogy between the two cases is striking.

To review: in both cases, a roughly one-and-a-half-minute vehicle pursuit initiated under suspicion of stolen vehicle ended in the shooting of an unarmed Black man within seconds of police arrival. In both cases Edric Talusan is the police driver. In both cases the shooting occurred in the Bayview Hunters Point neighborhood of San Francisco.

No practice or custom right?! There is, however, a key difference in the two cases.

To bring justice is the job of a jury which is exactly what was foreclosed upon by the summary judgement.

In 2013 all parties seem to concur that Talusan acted in the heat of the moment, moving quickly, perhaps somewhat erratically, and yelling at the top of his lungs. Contrast that with his conduct subsequent to the killing of O’Neil.

In Icky’s case, a mere seven seconds after we are led to believe that Talusan was surprised by his trainee’s murderous shot, he calmly walks out of his police vehicle and inspects the body without even unholstering his weapon. For someone surprised by a shooting and faced with not only the gravity of such a situation but possible criminal responsibility, this level of calm is almost unbelievable.

Of course, if he were not surprised by his trainee’s action, his response would be much more psychologically plausible. Speaking of plausibility, let’s return to the internal discipline of the SFPD.

Does it make more sense that Chief Bill Scott, who has had an uneven relationship with the SFPOA starting before he was even confirmed as chief, would have the nerve to demote Talusan from patrol duty on the sheer basis of failing to – in less than one second – stop his trainee from shooting, or that Chief Bill Scott realized in conjunction with the SFPOA that someone might put together the fact that a loose cannon was placed in a training capacity now resulting in a body count and that it was in the interest of the department’s image to remove him from visibility?

None of this line of inquiry is intended to remove accountability from Christopher Samayoa for Keita “Icky” O’Neil’s death. That Mr. Samayoa fired the killing shot is undisputed, and as such, the primary responsibility for O’Neil’s death falls on his shoulders regardless of the outcome of legal proceedings.

The rot is structural and New York’s First Deputy Commissioner William H.T. Smith said, “They [the public] are sick of ‘bobbing for rotten apples’ in the police barrel. They want an entirely new barrel that will never again become contaminated.”

Nor is it to say that we can definitively prove that Edric Talusan ordered the killing, despite some damning circumstantial evidence. But it is neither our job nor Judge Spero’s job to make that determination. That job belongs to a jury which is exactly what was foreclosed upon by the summary judgement.

To the more general question, though, the targeted prosecution of Samayoa is a case study in a dangerous longstanding police politic. As Professor Susan Bandes pointed out 20 years ago: “Once police conduct does reach a level that police management or the public are willing to recognize as criminal, it is recategorized as something other than police work. Now the cop is no longer a cop, but by definition, a rotten apple who in no way represents or taints the rest of the barrel.”

By this logic, excising Samayoa somehow would absolve the department of his unfortunate criminality. But it is quite clear that this is neither an appropriate analysis for the SFPD nor for that matter any police department in the United Capitalist Prison States of America. The rot is structural, and if it is not addressed as such, the deaths will continue.

This has been acknowledged for nearly five decades including by cops themselves. As New York’s First Deputy Commissioner William H.T. Smith said in the aftermath of Frank Serpico’s whistleblowing: “They [the public] are sick of ‘bobbing for rotten apples’ in the police barrel. They want an entirely new barrel that will never again become contaminated.”

I pray that Mama Judy and the rest of Icky’s family receive whatever pale semblance of reparation this wretched system will afford them. But we must remember that even if Samayoa goes down hard, this is not over until we heal from our collective Stockholm Syndrome and free ourselves from a law enforcement regime that has a thousand different ways to justify the extinguishing of Black life.

Jeremy Miller is co-director of the Idriss Stelley Foundation, part of the POOR Magazine family, organizer with the Black Alliance for Peace and a graduate of San Francisco State University. He can be reached at djasik87.9@gmail.com.

Store

Store