by Mariame Kaba with contributions by Lewis Wallace

Introduction: The origins of a rebellion

On Sept. 8, 1971, two prisoners were roughhousing in the yard at Attica prison. They were ordered by correctional officers to stop. An altercation ensued involving a few prisoners and guards. There is some confusion about what exactly happened during this incident. Regardless, later in the day, two prisoners were escorted by guards to the infamous “box” in Housing Block Z (HBZ). Prisoners at Attica had heard stories about what happened to people who were taken to segregation and none of what they heard was pretty. Stories of abuse, brutality and torture circulated; the guards did nothing to disabuse prisoners of these ideas.

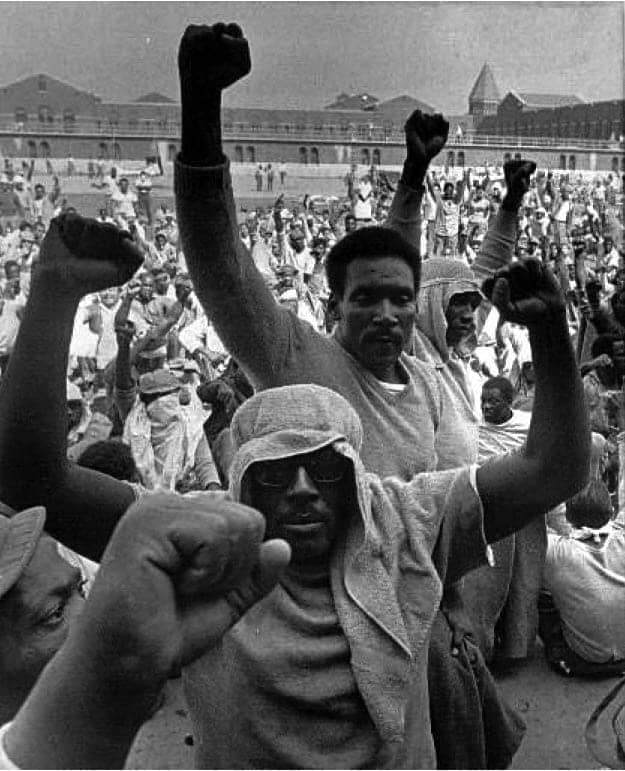

From Sept. 9 to 13, 1971, prisoners took control of the Attica Correctional Facility. They made a series of demands to prison administrators and held about 40 people as hostages. After four days of fruitless negotiations, Gov. Nelson Rockefeller ordered that the prison be retaken; 39 people were killed in a 15-minute assault by state police. The New York State Special Commission on Attica (also known as the McKay Commission) ap-pointed to investigate the uprising suggested: “With the exception of Indian massacres in the late 19th century, the State Police assault which ended the four-day prison uprising was the bloodiest one-day encounter between Americans since the Civil War.”

The uprising did not come out of nowhere. In September 1971 at Attica prison, there were over 2,200 people locked up in a facility built to accommodate 1,600. Of the 2,200, 54 percent were Black and 9 percent were identified as Puerto Rican. Forty percent of the prisoners were under the age of 30.

One out of 383 correctional officers was Latino and all of the prison administrators were white. It cost $8 million dollars to run Attica prison in fiscal year 1971-72; that amounted to about $8,000 per prisoner. Most of this money was spent on correctional officers’ salaries (62 percent). Inmates at Attica spent 14 to 16 hours a day in their 6-by-9-foot cells. They also worked about five hours a day and were paid between 20 cents and one dollar for their day’s labor. Prisoner Frank “Big Black” Smith offered his recollections of life at Attica in 1971:

“Conditions in 1971 was bad – bad food, bad educational programs, very, very low, low wages. What we called slave wages. Myself, I was working in the laundry and I was making like 30 cent a day, being the warden’s laundry boy. And I’m far from a boy.

“You get one shower a week. You know, a shower to us in Attica state prison is a bucket of water, and if you lucky and you get the right person outside of your cell that would bring you a second bucket, then you can wash half of your body with one bucket. What we would do is wash the top of our body with one bucket, and if we get a second bucket then we will wash the bottom part of our body. And you get one shower a week.

“The books in the library was outdated. They didn’t have any kind of positive recreation for us. If there was any recreation, it was minimum. It would only be on the weekends. And Attica is four prisons in one. You got A yard, B yard, C yard and D yard and two mess hall. And the only time you would see a person that’s in A block if you in B block, like I were, is when you would go to the mess hall and sometime you might run into him. “‘Dehumanizing,’ the word would be for the conditions in Attica in 1971 ((In “Voices of Freedom: An Oral History of the Civil Rights Movement from the 1950s through the 1980s” by Henry Hampton and Steve Fayer. New York: Bantam Books, 1990. Pp. 545-546.)).”

Prisoner Carlos Roche, interviewed for the documentary “Disturbing the Universe,” provided details about racial segregation at Attica:

“When I first went to Attica, they gave out ice once a year. Frozen water. They would bring it on the fourth of July and say, ‘White ice!’ Bring it in 55-gallon drums, open the door to the yard, throw it out on the ground and say, ‘White ice!’ and only white guys could get the ice. And they would take the drums back to the mess hall, fill them up again and bring it back and say, ‘Black ice!’ and anybody could take the ice, you know. And that was the first thing that hit me, and I mean it blew my mind. I was … I couldn’t believe it, you know. And that went on from ‘66 to ‘70. And then they stopped it in ‘70.

“Uh, haircuts was segregated, a white guy couldn’t cut a black guy’s hair or vice versa. Uh, the mail was insane. If I had a letter from a lawyer and I gave it to you to read, and the letter was found in your cell, we both went to the box. You got a year and I got two years. And every two days you did in seg, you lost a day of good time, you know. That was Attica, you know ((Interview with Attica Prisoner, Carlos Roche, from “Disturbing the Universe, a documentary about William Kunstler,” http://www.pbs.org/pov/disturbingtheuniverse/interview_roche.)).”

Attica had been on a slow boil throughout the summer of 1971. In May-June 1971, five Attica prisoners established the Attica Liberation Faction (ALF). The five founders were Frank Lott, who took the title of chairman, Donald Noble, Carl Jones-El, Herbert X. Blyden and Peter Butler.

Carl Jones-El suggested that the ALF was founded “to try to bring about some change in the conditions of Attica. We started teaching political ideology to ourselves. We read Marx, Lenin, Trotsky, Malcolm X, de Bois, Frederick Douglass and a lot of others. We tried a reform program on ourselves first before we started making petitions and so forth. We would hold political classes on weekends and point out that certain conditions were taking place and the money that was being made even though we weren’t getting the benefits ((“Voices From Inside: 7 Interviews with Attica Prisoners” (1972).)).”

Lee Bernstein (2010) provides some background about the founders of the Attica Liberation Faction: “These five – Frank Lott, Herbert X. Blyden, Donald Noble, Carl Jones-El and Peter Butler – were among the most experienced activists in Attica. Blyden had participated in a rebellion at the Tombs prison in New York City the previous year, helping to write the rebels’ list of demands. Others had been involved in a sit-down strike at Auburn prison.

“Blyden is credited with demanding that the prisoners be transported to a non-imperialist country as a condition of ending the takeover. While deemed impractical by one of the outside observers, this demand grew logically from the political education many inmates received while in prison. Blyden and Jones served on the negotiating committee during the takeover. Blyden was a member of Attica’s Nation of Islam community, and Carl Jones-El and Donald Noble were members of the prison’s Moorish Science community ((Bernstein, Lee (2010). “America Is the Prison: Arts and Politics in Prison in the 1970s.” Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.)).”

The McKay Commission suggested that during that summer, prisoners at Attica participated in peer-led classes in sociology. These were preceded by the formation of several study and discussion groups led by prisoners who had affiliations with the Nation of Islam, the Black Panther Party, the Young Lords and the Five Percenters. Carl Jones-El explains:

“The education department, the school system that they have, it only goes so far, far as trying to give a man an education. We more or less have to educate ourselves. When we came here [Attica] we knew the conditions and we felt that people should come together and get a better understanding of the conditions here, what was being did to them by the administration. So behind this we would hold meetings in the yard. We’d hold open house and whoever wanted to come and listen to our political ideology were welcome. We didn’t bar anyone. This was frowned upon by the institution and they would break it up. If we congregated too big, this wasn’t allowed.

“In order to reach everyone, we had to set up some sort of communications. We had to get along with the different factions here: the Muslims, the Five Percenters and all the other factions to become one solid movement, rather than just be separate parts here trying to accomplish the same things, better conditions for the inmates ((Edited transcription of separate interviews with nine of those the prison administration had isolated as “leaders” of the rebellion taken from interviews conducted by Bruce Soloway of Pacifica Radio, WBAI, in February 1972. In “We Are Attica: Interviews with Prisoners from Attica,” published by the Attica Defense Committee.)).”

These informal gatherings provided a forum for prisoners to debate and discuss the social and political issues of the day. The McKay Commission found that these prisoner-created spaces politicized and radicalized inmates and contributed to a series of protests in the summer of 1971.

In July 1971, the Attica Liberation Faction presented a list of 27 demands to Commissioner of Corrections Russell Oswald and Gov. Nelson Rockefeller. This list of demands was based on the “Folsom Prisoners’ Manifesto,” which had been crafted by Chicano prisoner Martin Sousa in support of a November 1970 prisoner strike in California. Carl Jones-El offered this description of the genesis of the manifesto and the prisoners’ motivations:

“We wanted to do things, let’s say, diplomatically. We were seeking reform. Although many were not in favor of reform, because they didn’t believe that the people would listen. So five of us had gotten together. This is how we started. We met in the yard and we’d draw up drafts as to proposals we should make. And we sought support from the entire population, the four different blocks. And the only way we could accomplish this was that by us not being able to see everyone in different blocks, we, more or less, had to get on the traveling list. In other words, if you were a baseball, a football, a softball official, and you were in a position to travel and get around to different blocks. So we did this.

“One of us would go to different blocks, and there we would set up an educational program, and bring to their attention what the manifesto was going to be about. So we got a lot of support on this. Then we moved on it. Everyone was not in favor of signing their names to it though, because they didn’t want to spotlight themselves. So five of us did.” ((Edited transcription of separate interviews with nine of those the prison administration had isolated as “leaders” of the rebellion taken from interviews conducted by Bruce Soloway of Pacifica Radio, WBAI, in February 1972. In “We Are Attica: Interviews with Prisoners from Attica,” published by the Attica Defense Committee.))

Commissioner Oswald did not act on the demands. Instead, the warden of Attica, Vincent Mancusi, responded “by increasing the frequency of cell searches, censoring all references to prison conditions from news sources, and announcing that there would be no prizes awarded to the winners of the upcoming Labor Day sporting competitions ((Bernstein, Lee (2010). “America Is the Prison: Arts and Politics in Prison in the 1970s.” Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.)).”

Donald Noble, a member of the Attica Liberation Faction, explains what the prisoners hoped to accomplish through the manifesto:

“Well, I’m one of the men whose name was on the manifesto [that] was submitted to Oswald. We submitted a manifesto, 28 demands, to Oswald in July. We also submitted one to Rockefeller. We also submitted one to Shirley Chisholm. We also submitted one to Arthur Eve and different other legislative people and lawyers and so forth. You know, we got a beautiful reply back from Oswald, think it was sometime in August. He acknowledged our letter and so forth, and he was enthused about the way the manifesto was drawn up, because this was more or less coincide with his ideas. And he stated that he is for all these here changes that we talked about, because he sees that they are needed, but to give him time.

“And, everybody went along with him, because a lot of us have had dealings with Oswald for years, coming back and forth while he’s sitting on the parole board. Like there was things that all he had to do was more or less get in touch with the warden here that would have gone into effect. And these things more or less didn’t take place. […] He said he was going to look into these things, but they would take time. So he came here. He made a speech, but the speech he made, a lot of people didn’t like it because he talked about long range things. But people wanted to know what he gonna do about the problem what exists here ((Edited transcription of separate interviews with nine of those the prison administration had isolated as “leaders” of the rebellion taken from interviews conducted by Bruce Soloway of Pacifica Radio, WBAI, in February 1972. In “We Are Attica: Interviews with Prisoners from Attica,” published by the Attica Defense Committee.)).”

When George Jackson was killed by correctional officers at San Quentin Prison in August 1971, his killing sparked protests including work stoppages at prisons across the U.S. At Attica, the different prisoner factions, which had previously found it difficult to unify in order to strengthen the likelihood that their demands would be enacted, were mobilized by the killing of Jackson. Donald Noble, one of the founders of the Attica Liberation Faction, explained it this way:

“What really solidified things was George Jackson’s death. This had a reaction on the people, one that we were trying to accomplish all along, to bring the people together. We thought, ‘How can we pay tribute to George Jackson?’ because a lot of us idolized him and things that he was doing and things that he was exposing about the system. So we decided that we would have a silent fast that whole day in honor of him. We would wear black armbands. No one was to eat anything that whole day. We noted that if the people could come together for this, then they could come together for other things ((Donald Noble, interview, in “Prisons on Fire: George Jackson, Attica, and Black Liberation,” audio CD (San Francisco: Freedom Archives, 2001).)).”

When George Jackson was killed by correctional officers at San Quentin Prison in August 1971, his killing sparked protests including work stoppages at prisons across the U.S.

The Attica prison uprising was the most dramatic and deadly of the post-Jackson killing protests. However, the seeds of the revolt had been sown way before Jackson’s death.

On the occasion of the 40th anniversary of the Attica prison revolt, we felt that it was a good time to both reflect on the conditions that precipitated the rebellion and to examine its legacy. In 1970, there were 48,497 people in federal and state prisons ((Langan, Patrick A. “Race of prisoners admitted to state and federal institutions, 1926-86.” NCJ-125618. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics (May 1991).)) in the U.S. By 2009, there were 1,613,740 ((Numbers for both years 1970 and 2009 exclude the jail population.)) individuals locked up in our federal and state prisons.

Mariame Kaba, founding director of Project NIA, which uses the principles of participatory community justice to redefine the goals of the criminal legal system to include the prevention of crime as well as community member involvement in addressing crime, can be reached at mariame@project-nia.org.

Attica Manifesto of July 2, 1971

The following is the list of demands that were presented to Commissioner of Corrections Russell Oswald and Gov. Nelson Rockefeller on July 2, 1971, by the Attica Liberation Faction:

We, the men of Attica prison, have been committed to the New York State Department of Corrections by the people of society for the purpose of correcting what has been deemed as social errors in behavior. Errors which have classified us as socially unacceptable until reprogrammed with new values and more thorough understanding as to our values and responsibilities as members of the outside community. The Attica Prison program in its structure and conditions have been enslaved on the pages of this Manifesto of Demands with the blood, sweat and tears of the inmates of this prison.

The program which we are submitted to under the façade of rehabilitation are relative to the ancient stupidity of pouring water on a drowning man, inasmuch as we are treated for our hostilities by our program administrators with their hostility as medication.

In our efforts to comprehend on a feeling level an existence contrary to violence, we are confronted by our captors with what is fair and just, we are victimized by the exploitation and the denial of the celebrated due process of law.

In our peaceful efforts to assemble in dissent as provided under this nation’s U.S. Constitution, we are in turn murdered, brutalized and framed on various criminal charges because we seek the rights and privileges of all American people.

In our efforts to intellectually expand in keeping with the outside world, through all categories of news media, we are systematically restricted and punitively remanded to isolation status when we insist on our human rights to the wisdom of awareness.

Manifesto of Demands

1. We Demand the constitutional rights of legal representation at the time of all parole board hearings and the protection from the procedures of the parole authorities whereby they permit no procedural safeguards such as an attorney for cross-examination of witnesses, witnesses in behalf of the parolee, at parole revocation hearings.

2. We Demand a change in medical staff and medical policy and procedure. The Attica prison hospital is totally inadequate, understaffed and prejudiced in the treatment of inmates. There are numerous “mistakes” made many times; improper and erroneous medication is given by untrained personnel. We also demand periodical check-ups on all prisoners and sufficient licensed practitioners 24 hours a day instead of inmates’ help that is used now.

3. We Demand adequate visiting conditions and facilities for the inmate and families of Attica prisoners. The visiting facilities at the prison are such as to preclude adequate visiting for inmates and their families.

4. We Demand an end to the segregation of prisoners from the mainline population because of their political beliefs. Some of the men in segregation units are confined there solely for political reasons and their segregation from other inmates is indefinite.

5. We Demand an end to the persecution and punishment of prisoners who practice the constitutional right of peaceful dissent. Prisoners at Attica and other New York prisons cannot be compelled to work, as these prisons were built for the purpose of housing prisoners and there is no mention as to the prisoners being required to work on prison jobs in order to remain in the mainline population and/or be considered for release. Many prison-ers believe their labor power is being exploited in order for the state to increase its economic power and to continue to expand its correctional industries (which are million-dollar complexes), yet do not develop working skills acceptable for employment in the outside society, and which do not pay the prisoner more than an average of 40 cents a day. Most prisoners never make more than 50 cents a day. Prisoners who refuse to work for the outrageous scale, or who strike, are punished and segregated without the access to the privileges shared by those who work; this is class legislation, class division, and creates hostilities within the prison.

6. We Demand an end to political persecution, racial persecution, and the denial of prisoner’s rights to subscribe to political papers, books or any other educational and current media chronicles that are forwarded through the U.S. mail.

7. We Demand that industries be allowed to enter the institutions and employ inmates to work eight hours a day and fit into the category of workers for scale wages. The working conditions in prisons do not develop working incentives parallel to the many jobs in the outside society, and a paroled prisoner faces many contradictions of the job that add to his difficulty in adjusting. Those industries outside who desire to enter prisons should be allowed to enter for the purpose of employment placement.

8. We Demand that inmates be granted the right to join or form labor unions.

9. We Demand that inmates be granted the right to support their own families; at present, thousands of welfare recipients have to divide their checks to support their imprisoned relatives, who without outside support, cannot even buy toilet articles or food. Men working on scale wages could support themselves and families while in prison.

10. We Demand that correctional officers be prosecuted as a matter of law for any act of cruel and unusual punishment where it is not a matter of life and death.

11. We Demand that all institutions using inmate labor be made to conform with the state and federal minimum wage laws.

12. We Demand an end to the escalating practice of physical brutality being perpetrated upon the inmates of New York State prisons.

13. We Demand the appointment of three lawyers from the New York State Bar Association to full-time positions for the provision of legal assistance to inmates seeking post-conviction relief and to act as a liaison between the administration and inmates for bringing inmates’ complaints to the attention of the administration.

14. We Demand the updating of industry working conditions to the standards provided for under New York state law.

15. We Demand the establishment of inmate worker’s insurance plan to provide compensation for work-related accidents.

16. We Demand the establishment of unionized vocational training programs comparable to that of the federal prison system which provides for union instructions, union pay scales and union membership upon completion of the vocational training course.

17. We Demand annual accounting of the inmates Recreational Fund and formulation of an inmate committee to give inmates a voice as to how such funds are used.

18. We Demand that the present Parole Board appointed by the governor be eradicated and replaced by the parole board elected by popular vote of the people. In a world where many crimes are punished by indeterminate sentences and where authority acts within secrecy and within vast discretion and given heavy weight to accusations by prison employees against inmates, inmates feel trapped unless they are willing to abandon their desire to be independent men.

20. We Demand an immediate end to the agitation of race relations by the prison administration of this state.

21. We Demand that the Department of Corrections furnish all prisoners with the services of ethnic counselors for the needed special services of the Brown and Black population of this prison.

22. We Demand an end to the discrimination in the judgment and quota of parole for Black and Brown people.

23. We Demand that all prisoners be present at the time their cells and property are being searched by the correctional officers of state prisons.

24. We Demand an end to the discrimination against prisoners when they appear before the Parole Board. Most prisoners are denied parole solely because of their prior records. Life sentences should not confine a man longer than 10 years, as seven years is the considered statute for a lifetime out of circulation, and if a man cannot be rehabilitated after a maximum of 10 years of constructive programs etc., then he belongs in a mental hygiene center, not a prison.

25. We Demand that better food be served to the inmates. The food is a gastronomical disaster. We also demand that drinking water be put on each table and that each inmate be allowed to take as much food as he wants and as much bread

In conclusion

We are firm in our resolve and we demand, as human beings, the dignity and justice that is due to us by our right of birth. We do not know how the present system of brutality and dehumanization and injustice has been allowed to be perpetrated in this day of enlightenment, but we are the living proof of its existence and we cannot allow it to continue.

The taxpayers who just happen to be our mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, daughters and sons should be made aware of how their tax dollars are being spent to deny their sons, brothers, fathers and uncles of justice, equality and dignity.

Declaration to the People of America, read on Sept. 9, 1971, by L.D. Barkley

The people of the United States of America: First of all we want it to be known that in the past we have had some very, very, treacherous experiences with the Department of Correction of New York state. They have promised us many things and they are giving us nothing except more of what we’ve already got: brutalization and murder inside this penitentiary. We do not intend to accept – to allow ourselves to accept – this situation again. Therefore, we have composed this declaration to the people of America to let them know exactly how we feel and what it is that they must do and what we want primarily, not what someone else wants for us. We’re talking about what we want. There seems to be a little misunderstanding about why this incident developed here at Attica and this declaration here will explain the reason:

The entire incident that has erupted here at Attica is not a result of the dastardly bushwhacking of the two prisoners, Sept. 8, 1971, but of the unmitigated oppression wrought by the racist administrative network of this prison throughout the year.

What has happened here is but the sound before the fury of those who are oppressed. We will not compromise on any terms except those terms that are agreeable to us. We’ve called upon all the conscientious citizens of America to assist us in putting an end to this situation that threatens the lives of not only us, but of each and every one of you as well. We have set forth demands that will bring us closer to the reality of the demise of these prison institutions that serve no useful purpose to the people of America, but to those who would enslave and exploit the people of America.

Our demands are such:

1. We want complete amnesty, meaning freedom from all and any physical, mental and legal reprisals.

2. We want now, speedy and safe transportation out of confinement to a non-imperialistic country.

3. We demand that the federal government intervene, so that we will be under direct federal jurisdiction.

4. We want the governor and the judiciary, namely Constance B. Motley, to guarantee that there will be no reprisals and we want all factions of the media to articulate this.

5. We urgently demand immediate negotiations through William M. Kunstler, attorney at law, 588 Ninth Ave., New York, New York; Assemblyman Arthur O. Eve of Buffalo; the Prisoner Solidarity Committee of New York; Minister Farrakhan of the Muslims. We want Huey P. Newton from the Black Panther Party and we want the chairman of the Young Lords Party. We want Clarence B. Jones of the Amsterdam News. We want Tom Wicker of the New York Times. We want Richard Roth from the Currier Express. We want the Fortune Society; Dave Anderson of the Urban League of Rochester; Brine Eva Barnes. We want Jim Hendling of the Democratic Late Chronicle of Detroit, Michigan. We guarantee the safe passage of all people to and from this institution. We invite all the people to come here and witness this degradation so that they can better know how to bring this degradation to an end. This is what we want.

— The Inmates of Attica Prison

The “Attica Manifesto of July 2, 1971,” and the “Declaration to the People of America of Sept. 9, 1971,” are reproduced from “Attica Prison Uprising 101, a short primer,” originally published as a Nia Dispatch by Project Nia.