Interview by Alka Joshi, introduction and transcription by Natasha Reid

As Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. once stated, riot is the language of the unheard; and so it comes as no surprise that the language of our underclass is of the same dialect that it has been for decades and even centuries, as the socio-political issues that plague Black communities have refused to subside and the outcry of our people continues to ring a mere murmur in the ears of the power elite and our fellow world citizens.

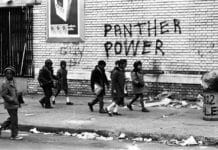

The Bayview community erupted in 1966, at the height of the civil rights movement, upon the unlawful police killing of 16-year-old Black youth Matthew “Peanut” Johnson. Police killings continue to haunt Black communities not only here in Bayview Hunters Point – rest in peace, Kenneth Harding – or even the Bay Area – Oscar Grant and Raheim Brown, to name but two stolen lives, remain in our hearts – but across the Atlantic too, in Black communities suffering the same injustices that burn fury in the consciousness of our people: a people of peace.

Our people of peace, when provoked tirelessly by the evils of police brutality, gentrification and a near genocidal prison system, stand together and claim a united voice: the voice of rebellion.

So to those young rebels fighting the oppression of Black people today in America, the United Kingdom and across the world, we stand in solidarity with your vision. The fight began long before the 1966 rebellion and continues to live on in the consciousness of every man and woman who has the courage to stand against the white supremacist state in which we live.

The following interview, conducted earlier this year by Alka Joshi, talking with her neighbors in Bayview Hunters Point who lived here then, gives an inside look at the 1966 uprising. Those rebels are present today in the consciousness of our youth: Our plight necessitates the continuation of their fight.

Man: That chain of events – [Nat] Burbridge [president of the San Francisco NAACP] had to take a stand on something. And the issue was: murder.

Woman 1: I realized that it was just, they were fighting for the right to be enabled to walk down the street and be equal, just like anybody else.

Man: I’m not just gon’ let you get away with doing anything to me and expect me to like it. And my stand is, is to fight back.

Woman 1: We were havin’ an Indian summer; it was warm that day.

Man: We were, you know, out in front of the house playing, like little kids do, and we heard tires squealin’ and saw a guy in a stolen car and he’s just wheelin’ around the schoolyard and doin’ doughnuts and stuff like this. At that time it was real exciting, ‘cause he was too young to be driving.

Man: Police cruisers came into the schoolyard. I can remember him doing a doughnut and heading towards the south end of the schoolyard and slammin’ on the breaks; the car slammed into one of the school benches and he jumped out and took off runnin’. He went to jump off the top of this little hill and I heard the gun crack; and I saw the body contort. They shot him! But they shot him in the back.

Mind you, I was a kid then. So I really didn’t understand all of the grumblin’ and the anger and stuff like this – I didn’t make the connection then. Well, he stole a car, he did somethin’ wrong; but, they didn’t have to kill him.

Newscaster from 1966 clip: It was as if a war had broken out on San Francisco’s city streets [the sound of people screaming in the background].

Woman 1: I could hear my mom on the phone, talkin’ about a riot; and, it’s like, you know, what is goin’ on? And then my brother, he says, he goes down to Third Street and he said the National Guard is out there. I can still visualize all the helicopters; I remember the police cars and paddy wagons that was goin’ back and forth.

Man: [inaudible] comin’ from everywhere, a lot of police sirens and stuff like this.

Woman 1: Shots were fired around the Opera House, which was just down the street from my school.

Man: A whole lot of Black people gathered in the streets and they were shoutin’: “Piggy, wiggy! Ooo ooo, you gotta go now. Oink oink.”

Woman 1: It was really, it was just a mess, it really was. It really, really was a mess.

Woman 2: I have been in Bayview for 48 years. My parents purchased a home here a month before I was born.

Man: My dad was in the Navy.

Woman 2: My dad was in the military. He was a porter on the Southern Pacific railroad. 1964, when they came here and bought the house, [there were] very few places that would allow Blacks to move [in]. But finally, I was someplace where I could run up and down the street and have a big back yard, and I was just so happy. I was just so happy in the Bayview.

Man: Third Street was a beautiful place. We didn’t even have to go out of the community, basically, for anything. Everything we needed was right there. It was such a thrill to have a quarter and to be able to go to Third Street, to the candy store.

Woman 1: Half of the counter was full of candy. And it was so, it would just be so fun to go down there and just pick up all the candy you want!

Everybody would come home and do their homework; and if it was a nice day, somebody would try to talk their parent into hangin’ outside. If we had one parent outside, everybody was able to stay out. And sometimes one parent would fix hot dogs and chips, or one parent would fix French fries and maybe a sandwich; and we all shared it together.

And we would get on somebody’s stairs or we would sit in the driveway and just sit out and eat and have fun.

Woman 2: The demographics when we moved in ’64 here was very diverse. White, Black, we had an Asian family that they still live down there.

Man: This was all Russian and Italian before we moved down here: Russian, Italian, a few Chinese, but no Hispanics.

Woman 2: Didn’t feel any type of racial tension, really didn’t at all. At least I didn’t. Everybody was just so nice. I can still look around and think about – I probably went into everybody’s house on this whole entire block.

Things were so different: If you as a child was rude to someone, or another neighbor saw that you were doing something, they would go and tell your parents, but they would spank you!

Woman 1: Then you went home and got disciplined. You got disciplined at school, [so] you walk down the street and somebody don’t know what happened [says], “What you doin’ goin’ home at this time of day?” You got in trouble with them; you got in trouble with who was at home; and then, you might even get in trouble when your daddy came home [laughs].

Woman 2: The stores that were down on Third Street – I didn’t even think anything about walkin’ down Third Street. We would go shopping down Third Street all the time, walk down there never worried about anything really happening. It was really a nice place to shop.

Woman 1: One family on the other block, they would get tickets for the Giants and we would pack up a lunch and we would go walkin’ off to Candlestick. And then, the thing about it, it wasn’t just African American children: We had all nationalities, all religions. But we had a good time.

Woman 2: You have to remember the shipyard was still open too. And you hear the Navy that was down there – you could hear it in the morning, you could actually hear the trumpets with revelry, taps in the evening at 10 o’clock and just sailors all over the place, just all over the place. You couldn’t even get a seat on the bus ‘cause it was just packed with the sailors! So I thought that was cool too, how we had the Navy …

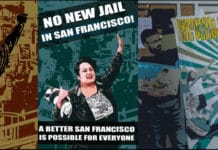

Man: After the riots, most of the business started movin’ out. Immediate. They got the glass back in the place pretty quick, but, as I can remember, [a] few places stayed empty.

After the ’66 riots, that’s when the white flight took and people moved down to the Peninsula, mainly to escape from here. And that’s when Bayview really got a bad reputation. And it was that nobody cared; nobody cared at all and I felt it was so sad to walk down Third Street or drive down Third Street and see all these abandoned places and nobody cared any more. People just packed up and they left.

Some of the places, they’re still there but they’ve changed over the years. They’ve changed owners. At Third and Palou, we had Rexall drugstore; we had, oh God what was that, it was like a five and dime store; it was just all these cute little boutiques and places you could go in and buy …

Man: With the riots and stuff, what the riots and stuff did was basically just highlight the injustices. Some of my best friends back then were white, so, you know, it really messed me up. All of that to me, kinda liked shaped me as a child.

Woman 2: There was some Maltese out here and that was sad too, to see them leave. They used to have their social club on Oakdale.

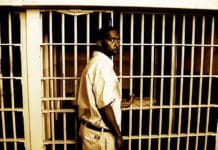

Man: I remember one kid that happened to be a good friend of mine named Michael Wilson, ended up gettin’ caught up in that mess and he was only 6 or 7, but he was down on Third Street with the rest of ‘em, you know. And I can only wonder today, if that had anything to do with him, you know, bein’ in and out of prison, you know, like myself.

Woman 2: People who wore uniforms, like even like mailmen, anybody that was in a uniform, they took it as like that they were the cops or something – that you don’t belong here type of thing.

Man: Somewhere around here shortly after, they would bus in children from the other neighborhoods …

Woman 2: When I got old enough to move away – I left when I was 17, soon as I graduated – I was just so happy to get away from here.

Man: The mentality of the people is totally different now than it was back then. We’d look out for you. If we saw you everyday, then you’d have people lookin’ out for you. Now people, especially in the Bayview, really don’t care. They see a crime happenin’ and they look the other way, “Oh well.” That’s the way it is, you know. So there is no, no genuine love and care and any more.

Woman 2: I hated this place so much, just hated it, because of everything that had happened in the past and all the violence.

News broadcast from ’66:

News anchor: “Is there going to be more trouble tonight?”

Interviewee: “I don’t know if there’s gonna be more trouble and if I did know I wouldn’t say, because I don’t think, I wouldn’t trust a white man as long as I live – never again. I know I gotta go to him for a job. I know I gotta go to a white man’s school and I’ll go. But if they don’t want to treat me right, I ain’t got to beg, ‘cause I wasn’t accustomed to beggin’: I got pride.

Woman 2: I think that the kids that did it, they had so much anger anyway simmering inside of them. I don’t think that it was something that could have been avoided. There was just too many deep rooted anger. If it wasn’t that [the police killing] it would’ve been somethin’ else, I think, it would’ve been somethin’ else.

But yeah, I kind of wish they would’ve found a more constructive way of going about things. I mean, didn’t they, I mean Martin Luther King was still alive at that time. It’s like, didn’t they pay attention to, you know, anything that he said, you know? He would have never consented to that sort.

So but what I would of hoped to happen is that it never happened.

Man: If you suffered some of the things that we suffered as a people, as a people, there’s a lot of stuff – we gon’ make you go on and we gonna stand up. We gonna support each other. I don’t think the law is always right, because there’s an element of humanity there. I mean, what is morally right? Not according to the law, but by human beings.

Alka Joshi, who recorded this interview, was born and raised in India until the age of 9, when her family immigrated to America. She graduated from Stanford and worked for 25 years, then in the advertising industry before enrolling in the MFA program at California College of the Arts. Earlier this year, she interviewed three of her African American neighbors to learn more about the lingering emotional and economic scars that stem from the Hunters Point rebellion 40 years ago. Joshi can be reached at creativewiz@earthlink.net. You can listen to this interview at http://www.samizdat.me/oral-history-san-francisco-bayview-1966-race-riot/.

Natasha Reid, who transcribed the interview and wrote the introduction, is a writer of Zimbabwean and Scottish descent. She holds an honors law degree, though her real passion lies in journalism and political awareness. You can contact her at tash.reid7@gmail.com.

Store

Store