by Jean Casella and James Ridgeway

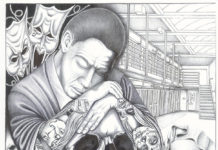

A comprehensive new article by Brandon Keim in Wired Science is titled “The Horrible Psychology of Solitary Confinement.” Keim does an excellent job of summing up the research on the psychological effects of solitary. He also points to the relative lack of cutting-edge neuroscientific research on the subject, which might show the physical effects isolation has on the brain. (We wrote about one such study here.) An excerpt follows, but the article is well worth reading in full.

“Consistent patterns emerge, centering around the aforementioned extreme anxiety, anger, hallucinations, mood swings and flatness, and loss of impulse control. In the absence of stimuli, prisoners may also become hypersensitive to any stimuli at all. Often they obsess uncontrollably, as if their minds didn’t belong to them, over tiny details or personal grievances. Panic attacks are routine, as is depression and loss of memory and cognitive function.

“According to Kupers [psychiatrist Terry Kupers of the Wright Institute, a prominent critic of solitary confinement], who is serving as an expert witness in an ongoing lawsuit over California’s solitary confinement practices, prisoners in isolation account for just 5 percent of the total prison population, but nearly half of its suicides.

“When prisoners leave solitary confinement and re-enter society – something that often happens with no transition period – their symptoms might abate, but they’re unable to adjust. ‘I’ve called this the decimation of life skills,’ said Kupers. ‘It destroys one’s capacity to relate socially, to work, to play, to hold a job or enjoy life.’…

“Explaining why isolation is so damaging is complicated, but can be distilled to basic human needs for social interaction and sensory stimulation, along with a lack of the social reinforcement that prevents everyday concerns from snowballing into pychoses, said Kupers.

“He likened the symptoms seen in solitary prisoners to those seen in soldiers suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. The conditions are similar, and it’s known from studies of soldiers that chronic, severe stress alters pathways in the brain.

“Brain imaging studies of prisoners are lacking, though, given the logistical difficulties of conducting them in high-security conditions.

“Such studies are arguably not needed, as the symptoms of solitary confinement are so well-described, but could add a degree of neurobiological specificity to the discussion.

“‘What you get from a brain scan is the ability to point to something concrete,’ said law professor Amanda Pustilnik of the University of Maryland, who specializes in the intersection of neuroscience and the legal system. ‘The credibility of psychology in the public mind is very low, whereas the credibility of our newest set of brain tools is very high.’

“Brain imaging might also convey the damages of solitary confinement in a more compelling way. ‘There are few people who say that mental distress is impermissible in punishment. But we do think harming people physically is impermissible,’ Pustilnik said.

“‘You can’t starve people. You can’t put them into a hotbox or maim them,’ she continued. ‘If you could do brain scans to show that people suffer permanent damage, that could make solitary look less like some form of distress, and more like the infliction of a permanent disfigurement.’”

James Ridgeway and Jean Casella are co-editors of Solitary Watch, an innovative public website aimed at bringing the widespread use of solitary confinement out of the shadows and into the light of the public square. Solitary Watch, where this story first appeared, provides the public – as well as practicing attorneys, legal scholars, law enforcement and corrections officers, policymakers, educators, advocates and prisoners – with the first centralized, comprehensive source of information on solitary confinement in the United States.

Store

Store