by Rallie Murray

What are the effects of long-term incarceration on prisoners? In a country where mass incarceration has become the norm, what responsibilities do the state and the community have to prisoners and to protecting some of their most basic freedoms – access to health and freedom from torture being chief among them? Part of the problem, I believe, is the way in which the United States thinks about health care and about rights in general. When prisoners are held to be the villains of society and considered somehow less than the rest of us, how can the community ensure that their humanity is not infringed upon?

The desire to penalize, to punish rather than correct or rehabilitate in the prison industrial complex, fundamentally undermines a rights-based discourse on health and human rights as it establishes prisoners as needing to regain their status as individuals deserving of such rights. The penal system itself, most especially as exemplified through maximum security prisons and long-term solitary confinement, is designed around the principle that no such “rights” are sacred.

This shift in the nature and design of the prison system points to the birth of the penal harm movement. The penal harm movement implements punitive measures designed to make prisoners suffer as much as possible, supposedly to correct their behavior through negative associations with undesirable actions. Within such an ideology, supermax prisons emerge as a culture of harm that constantly intensifies itself in order to remain effective.

In such an environment, prisoners are stripped of their status as human beings by the simple fact of their treatment – depriving individuals of the trappings of humanity and constructing them as the villains of society deserving of the worst treatment imaginable renders them no longer quite human in the eyes of guards and other prison staff. The fact of their punishment renders them outside the body of the state, making it difficult if not impossible to make a rights-based discourse on health and human rights intelligible within public opinion.

In a rights-based health discourse, the state holds undeniable power over bodies which are deemed to be no longer fit or deserving of rights, whether based on previous behavior or other categories of social illegitimacy. Once an individual or a community is cast outside that realm of innocence and social legitimacy, however, they are relegated to a separate category of existence which is denied access to what are generally considered to be inalienable human rights.

The penal system itself, most especially as exemplified through maximum security prisons and long-term solitary confinement, is designed around the principle that no such “rights” are sacred.

A rights-based discourse on health would rather concern itself with innocents dying of infectious diseases than with prisoners afflicted with the same diseases, to the extent that willful neglect within the prison system has a discernible, quantifiable affect on bodies that come into contact with it regardless of the duration of that contact. Thus a human-rights based discourse on health actively denies access to those bearing certain kinds of social stigma – not the least of which include prisoners within administrative segregation (AdSeg) or other types of solitary confinement within prison systems in the United States.

In order to construct a meaningful understanding of the ways in which delegitimized bodies are affected both by lack of health care and by the effects of social stigma and stress, it is necessary to reformulate the ways in which health and health care are understood outside of a discourse on human rights. Human rights are not enough because of the simple fact that they can be denied.

Instead, health can be understood as an integral aspect of anti-capitalist and anti-state organizing. When the good health of individuals, the community and even the planet is internalized as a community concern instead of an individualistic necessity, part of the power of the state to define and control our bodies is in itself diminished.

The World Health Organization defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” This is a useful starting point for understanding health in prisons, particularly when one takes into account the effects of solitary confinement on an individual’s sense of identity and personhood.

The kind of understimulation and complete control of an empty routine experienced by prisoners within supermax prisons can increase an individual’s level of stress. Long-term exposure to stress has very real effects on health. The brain processes loneliness in the same area as physical pain, thus the lived reality of long-term or indefinite solitary confinement has just as much an effect on the bodies as it does on the minds of inmates.

In the barest terms, constant exposure to stress can lead to chronic increased heart rate, which in turn can lead to high blood pressure and other health concerns. Add to this the spread of chronic diseases through inhumane and unsanitary living conditions as well as systematic neglect on the part of medical practitioners due to lack of critical resources, and it becomes very clear how destructive the prison system is to the bodies of the incarcerated.

Currently in the prison system, 31 percent of inmates have a learning or speech disability, a hearing or vision problem, or a mental or physical condition. Twelve percent of inmates are physically impaired in some way. One in eight prisoners receives therapy or counseling of some kind. One third of all prisoners in the United States will be injured within the first two years of their imprisonment.

The brain processes loneliness in the same area as physical pain, thus the lived reality of long-term or indefinite solitary confinement has just as much an effect on the bodies as it does on the minds of inmates.

In terms of raw health disparities, chronic infectious diseases are epidemic within the prison system – more than 800,000 inmates report having one or more chronic medical conditions – and their access to care could be described as poor at best. Since 1992, there have been on average six times as many cases of tuberculosis reported within the prison system as within the general United States population, seven times more prisoners diagnosed with HIV, and 14 times more living with AIDS. Prison levels of hepatitis B infections are estimated at a range of 8 percent to 43 percent, between two and 20 times the reported hepatitis B cases in non-incarcerated populations.

Additionally, according to a study of the health of prisoners in United States federal and state prisons and jails, the prevalence of diabetes, hypertension and persistent asthma were found to be higher than in the non-incarcerated population. In California, on average one prisoner dies every week from insufficient medical care, and nearly everyone in supermax has a serious medical issue.

Lack of treatment clearly has adverse physical effects on inmates throughout the prison system. Among inmates with a persistent medical problem, 13.9 percent of federal inmates, 20.1 percent of state inmates and 68.4 percent of local jail inmates had received no medical examination since incarceration.

Given that a 1976 Supreme Court case found willful neglect of prisoner health to be a violation of the Eighth Amendment, it seems incredible that this system is able to continue to destroy the bodies and minds of individuals. But this is where a rights-based discourse on health and care fails prisoners: Despite a Supreme Court decision that their good health is a constitutionally granted right, it is fundamentally denied to prisoners locked away in solitary confinement, obfuscated and rendered less than human by the same state that purports to support their right to health.

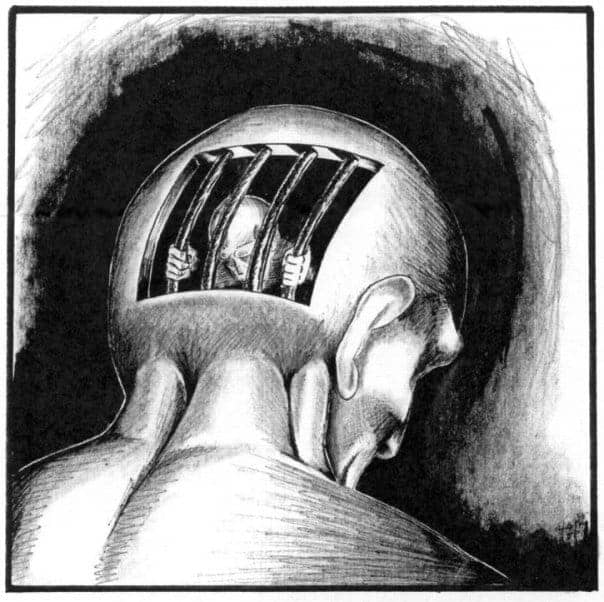

The prison is a means of disciplining and controlling the mind as well as the bodies of inmates, and complete separation from all other life has devastating effects on the mental well-being of prisoners in solitary confinement. The sensory deprivation of complete isolation has been linked to long-term psychological illness by Stuart Grassian of Harvard Medical School, and the kind of mental fracturing that occurs under such conditions is ultimately advantageous to the prison system itself.

That long-term solitary confinement has psychological effects on prisoners is not new information, nor has it been entirely unrecognized by the United States government. Yet despite this recognition, prisoners continue to be sent to maximum security facilities and placed in indefinite solitary confinement. If, as Hannah Arendt wrote, “the destruction of a man’s rights, the killing of the juridical person in him, is a prerequisite for dominating him entirely,” it is through the psychological torture of social abandonment that such domination and destruction is carried out within the supermax.

Despite a Supreme Court decision that their good health is a constitutionally granted right, it is fundamentally denied to prisoners locked away in solitary confinement, obfuscated and rendered less than human by the same state that purports to support their right to health.

Aside from the obvious impact that lack of treatment for health concerns, the oppressive environment of maximum security prisons impacts the health and wellbeing of incarcerated persons. The prison itself acts as a space in which a culture of harm coincides with the penal harm movement to produce a feedback loop of torture and abandonment – the role of the prison itself is no longer to discipline bodies that are refusing to be subjected and productive.

Instead, the very environment of the prison is designed to strip away the humanity of prisoners and abandon them outside social space. In an oppressive environment such as this, where physical, mental and emotional conditions remain untreated, the effects of the relationships between physical, social and environmental impacts have the potential to carry out the destruction of bodies on behalf of the state.

Rallie Murray, a graduate student at the California Institute of Integral Studies studying prison activism with Anthropology Department Chair Andrej Grubacic, can be reached at rxmurray13@gmail.com.