by Duncan Tarr

Introduction

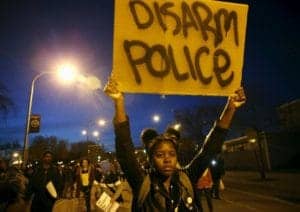

On April 19, 2015, Freddie Gray of Baltimore, Maryland, was murdered by officers of the Baltimore Police Department while in their custody. An article published in The Atlantic three days after Gray’s death pointed out the historical precedent for this particular kind of state violence.

The author wrote, “Black men dying at the hands of the police is of course nothing new” and that “African Americans around the nation … experience the police not as benevolent defenders of the peace but as an arbitrary menace, more likely to violate a citizen’s rights than preserve them.”[i]

These statements would most likely be met with nods of agreement by the readers of The Atlantic, yet they raise many more questions than they answer. In 2015, the obvious contradiction of a government agency “keeping the peace” while simultaneously posing a violent threat to Black communities seems remarkable even by the low standards of American liberalism.

However, the “peculiar institution” of this violent and racist system can be better understood by tracing the lineage of the police back in time.

Many of the U.S. metropolitan police forces that exist today were created via legislation in the decades immediately before the Civil War. Military-style police forces first emerged in Southern urban areas out of the tradition of slave patrols and in order to curb the threat of slave revolts, but they took many cues from their Northern urban neighbors who were more concerned with working class riots and labor unrest.

The Chicago Police were created over a couple of years beginning in 1855 and were explicitly modeled on the New York Police Department, created in 1845, which in turn was modeled on the London Metropolitan Police Service, created in 1829.[ii] A law passed by the Maryland state legislature in 1853 created the modern Baltimore police force.[iii]

By reading the writings from this era we learn that the creation of the Baltimore police force was a political decision to better control the urban working class, including the free and enslaved Black population in order to better secure their labor power. By reading articles in both the white press and the Black press, we learn that the consolidation of the police force was a decision made to control bodies, labor and public space, not merely to create a more “professional” or moral force.

The 1853 law

To answer some of these questions, we return not to the Baltimore of Freddie Gray, but instead to the Baltimore of Frederick Douglass, who spent some of his life as a slave in the city. A single law passed in 1853 created the first Baltimore Police Department.

The law is described as “AN ACT to provide for the better security of life and property in the city of Baltimore, by increasing and arming the police force thereof.” By examining what revolutionary theorist Gramsci calls “the apparatus of state coercive power which ‘legally’ enforces discipline,” we can better understand “the general direction imposed on social life by the dominant … group.” By additionally examining the counter-narratives in the Black press, we can see the early effects the new police force had on the Black community.[iv]

The 1853 bill covered many different aspects of the new police organization. It described the new force as having been created “to preserve the peace, and better to secure the safety of persons and property in the city of Baltimore” and stated the new “men” should be “liberally paid.”

The law also specified that the police would be armed appropriately, and it repealed an 1812 law that limited the number of bailiffs to 100.[v] The law’s effects were felt almost immediately: The size of the force grew from under 100 to about 270 men in just 15 days.[vi]

The specter of the working-class riot was prominent in discussions of the new police law. In 1835 in Baltimore, an angry mob of white lower-class men set out to attack the homes of bank directors but changed their minds midway and attacked a Black neighborhood instead. Even though the riot descended into racial violence, its initial target “bespoke the anxieties – not just or mainly centering on fears of Black competition for jobs – of a working population experiencing new forms of industrial discipline.”[vii]

One article from the Jan. 27, 1853, edition of The Baltimore Sun argued that there was a need to put down these “riotous collisions.” The Baltimore Sun was, and is, a “mainstream” newspaper that can be understood as reflecting the general outlook of the dominant social group. In antebellum Baltimore, this group was white, property-holding men.

The author of this particular article hoped that the new police force would make sure that “disorderly and disreputable collections of half-grown boys and young men at the corners of the streets may be promptly dispersed.” Because of the mixed-race workplaces and co-mingling of slaves, free Blacks, and working whites in the city, it is likely that the “collections” described by this author included poor and working men of all skin colors.[viii]

The article also argued that the new police force would save the city money in the long run because “All the cost of such a system as this will be amply requited in the improved value of real estate, the returns upon invested capital, and the moral tone of society.” More simply put, by removing the “disorderly and disreputable collections” from the streets of Baltimore, there would be higher returns on the investments of capitalists.[ix]

The author also argued that while it was necessary to arm the police, it was still more important (and cheaper) that police authority rest upon “moral force” rather than “the material element lodged in gunpowder, bullets, and revolvers.” The author warned, presciently, “the use of [arms] heedlessly or needlessly two or three times would bring the system itself into disrepute.” The proposal to arm the police clearly raised goosebumps on the skin of even those most dedicated to the “improved value of real estate.”[x]

Another Sun article, written following the passage of the new police law, argued that the growth of manufacturing in the city is tied to the need for reorganizing the police.[xi] The author tried to explain, “We all have a personal and almost vital business interest in the respective processes of human enterprise connected with our city.”

The logic: The growth of commerce benefits everyone, and police will better protect the growth of commerce; therefore, police will benefit everyone.[xii] Many other Sun articles shared the excitement about the possibilities for a new organization with “military precision” to better suppress the “tumultuous or riotous” assemblages in the city.[xiii]

In cities across the country, new “floating” populations were created by rural-to-urban migration. Baltimore became a destination for runaway slaves who were able to easily blend into a large free Black population, a population that by 1820 was more than double that of the enslaved Black population and the only place in Maryland where free Blacks outnumbered slaves by any number.[xiv]

Cities such as Lynn, Massachusetts, also experienced a massive influx of workers. They created a police force specifically to deal with this new population as well as to meet the “broader need to protect the social order in which private property was a fundamental institution.”[xv]

In Baltimore, the protection of a social system based on private property took on new and sinister meanings because white people held Black people as property. The Lynn police were supposed to protect factory equipment from sabotage, whereas the Baltimore police were supposed to protect potential fugitive slaves from “sabotaging” their status as property.[xvi]

In all these cases, the police are seen within a heavily gendered understanding of public space. A historian of the Chicago Police Department described the gendered construction of the Chicago cops and how “[u]ltimately, police departments were created by men in order to control the behavior of other men.”[xvii]

Despite women, children, and men working in various industries in the city, the Baltimore Sun articles described the police as dealing with only men. In this sense, the creation of the police in Baltimore had to do less with controlling a gendered workforce and more with controlling urban space imagined to be filled with the bodies of men, bodies who could easily become participants in a specifically masculinized threat to private property: the working-class riot.

However, the violent threat that police posed to women – and especially Black women – came to the forefront during the Civil War. During the war, Black men in Alabama organized the National Lincoln Association to protect Black women from sexual assault committed by policemen.[xviii] Even if not officially sanctioned, the early “professional” police played an important role in upholding white supremacy through sexual violence, despite the early focus in Baltimore newspapers of controlling poor and working class men.

The Black Press

The Black and abolitionist press of this time offered a more nuanced account of the emerging urban police forces and directly challenged some of the reporting on police violence in The Baltimore Sun.[xix] The articles within the Black press about the centralization of the police provide a more critical perspective.

A typical article described one 1854 case in which two policemen arrested a Black boy for vagrancy in the city and then sold him as a slave into the countryside.[xx] Another typical article detailed an instance in which two police officers, without any warrant, arrested a free Black man on suspicion of being a runaway.[xxi]

Another article warning of the dangers of the new police described how white Baltimoreans were linking the increase in the number of free Black residents in the city with the increase in runaway slaves and assumed that the free Blacks were assisting the runaways on their journeys north. The pro-slavery article called the free Black population “undesirable” and the Black paper warned its readers, “It is deemed probable that the chief means of protection relied on will be the formation of a vigilant border police and suitable regulations for the free negro population.”[xxii]

The pro-slavery article directly linked a stronger police force to more effective control over the human property of slaveholders and those free Blacks that aided runaway slaves.

An 1859 convention of Maryland’s slaveholders also echoed the desire for a stricter police force to regulate Maryland’s Black population. The group coalesced around a program for much stricter surveillance of the Black population.

The slaveholders supported the formation of an “efficient Black police system throughout the State, whose duties shall extend to all classes of negroes, slaves as well as free.” These slaveholders, many from rural areas, came to the same consensus as the mostly urban manufacturers: A larger, more efficient and more powerful police force will better secure the productive forces of the workers, both Black and white.[xxiii]

However, there was a divide within the Black community. Some Black writers had faith that a more professional police force could offer better protection for them. They did not view the police as specifically a weapon for class control and instead saw possibilities for the cops to stop the illegal Atlantic slave trade.[xxiv] Also, police forces were cited as helping to protect abolitionist newspaper offices and meetings of free Blacks from attacks.[xxv]

Following the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, government officials in Northern “free” states were supposed to return fugitive slaves to the South. Policemen were very often the ones on the ground enforcing the act.

Individual officers clearly understood the new direct link between their job and the national legislation. One cop in Boston resigned in protest rather than become a “slave-hunter.”[xxvi] Although their language does not explicitly link them, both the municipal police legislation and the Fugitive Slave Act were part of the larger shift from an “unimaginably sparse criminal justice system” towards more centralized state control that included a centralized and armed police force.[xxvii]

State control, police power

The birth of the modern Baltimore police force represented a political decision to manipulate the relationship between individuals and the state. The employing class in the city of Baltimore was surprisingly transparent in their decision to consolidate the system of policing.

It is understandable that Black Baltimore and the abolitionist press believed that they could leverage the new police power to their advantage, especially to curb the illegal slave trade and prevent attacks on abolitionist property and meetings of free Blacks. But the Baltimore police were not created by the abolitionists, they were not created by the discontented working class, and they were certainly not created by Black people.

The police were created by white elites and their sympathizers as they sought to more effectively exert control over a disorderly urban population. The police laws passed in this period can be seen as one battle among many in the ongoing war over control of the public urban space.[xxviii]

When the mayor of Baltimore referred to the function of the police as protecting “good order, peace, and safety of the State,” he was explicitly talking about disciplining workers so that employers would have access to a workforce – Black or white, slave or free – that was both obedient and exploitable. This means that the creation of the professional police “attests to the idea of labor as public property.”[xxix]

Dr. Bryan Wagner argued: “Police relates to Blackness not as practice but simply as a power …. Though the controlling cases on the police power from the antebellum decades concern not slaves but wharves and paupers and liquor, these cases are directly relevant to Blackness because they declare the self-evidence of the police power, and police comes closest to Blackness at the point where it passes into self-evidence.”[xxx]

During the public discussion over the 1853 Baltimore police law, the fundamental political nature of the police force was made more explicit and obvious to the public. In the public debate around the police law and the descriptions of police functions, elites and the Black and white lower classes traced their political desires onto the new police.

Because the police were made for a purpose that was fundamentally antagonistic to the lower classes, the few perks that professionalization granted were overshadowed by the state’s intended uses of coercion and control.

Bibliography

Secondary sources:

Blackmon, Douglas A. “Slavery By Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black People in America from the Civil War to World War II.” New York: Doubleday Books, 2008.

Campbell, Stanley W. “The Slave Catchers: Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850-1860.” Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1968, 1970.

Dawley, Alan. “Class and Community: The Industrial Revolution in Lynn.” Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1976, 2000.

Douglass, Frederick. “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, Written By Himself. A New Critical Edition by Angela Y. Davis.” San Francisco, City Lights Books, 2010. Originally published 1845.

DuBois, W.E.B. “Black Reconstruction in America 1860-1880.” New York, 1971. Originally published 1935.

Egerton, Douglas R. “He Shall Go Out Free: The Lives of Denmark Vesey.” Oxford: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2004.

Foner, Eric. “Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad.” New York and London: W.W. Norton and Co., 2015.

Gramsci, Antonio. “Intellectuals and Education” in “The Antonio Gramsci Reader: Selected Writings 1916-1935.” Edited by David Forgacs. New York City: New York University Press, 1988.

Gutman, Herbert G. “The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom, 1750-1925.” New York: Pantheon Books, 1976.

Hunter, Tera. “To ‘Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors After the Civil War.” Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1997.

Mitrani, Sam. “The Rise of the Chicago Police Department: Class and Conflict, 1850-1894.” Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 2013.

Rockman, Seth. “Scraping By: Wage Labor, Slavery, and Survival in Early Baltimore.” Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009.

Roediger, David R. “The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class.” London and New York: Verso Books, 1991.

Wagner, Bryan. “Disturbing the Peace: Black Culture and the Police Power after Slavery.” Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2009.

Newspapers

The Baltimore Sun:

“Arming the Police” in The Baltimore Sun, Jan. 27, 1853: 2. Accessed online on April 5, 2016.

“The City Councils and the New Police System” in The Baltimore Sun, April 11, 1853: 1. Accessed online on April 5, 2016.

“London and Baltimore Police” in The Baltimore Sun, March 31, 1853: 2. Accessed online on April 3, 2016.

“The Rioters: City Police: Before John Swift, Mayor” in The Baltimore Sun, May 23, 1838: 1. Accessed online on April 5, 2016.

Frederick Douglass’ Paper:

“The First Victim under the New Fugitive Slave Bill” in Frederick Douglass’ Paper, Page [2], Volume III, Issue 41. Oct. 3, 1850. Rochester, New York. Accessed online on April 7, 2016.

“A Hard Case” in Frederick Douglass’ Paper, Aug. 17, 1855, Page 4, Volume VIII, Issue 35. Rochester, New York. Accessed online on April 6, 2016.

“An Incident in the History of Slavery” in Frederick Douglass’ Paper, Nov. 30, 1855, Page 3, Volume VIII, Issue 50. Rochester, New York. Accessed online on April 6, 2016.

“Look out for the Slave-Catchers, to the Editor of the N. Y. Tribune Sir” in Frederick Douglass’ Paper, Page [1], Volume VIII, Issue 13. March 16, 1855. Rochester, New York. Accessed online on April 3, 2016.

“Mistaking a Black Republican for a Red Republican” in Frederick Douglass’ Paper, Page [3], Volume XII, Issue 6. Jan. 21, 1859. Rochester, New York. Accessed online on April 6, 2016.

“The Slave Case at Harrisburg: Arrest of a Negro Supposed to be a Fugitive Slave from Virginia – Great Excitement” in Frederick Douglass’ Paper, Page 3, Volume XII, Issue 17. April 8, 1859. Rochester, New York. Accessed online on April 6, 2016.

“Slave Stampedes in Maryland” in Frederick Douglass’ Paper, Page [3], Volume XI, Issue 41. Sept. 24, 1858. Rochester, New York. Accessed online on April 7, 2016.

“The Uses of Adversity” in Frederick Douglass’ Paper, Sept. 24, 1852. Rochester, New York. Accessed online on April 5, 2016.

The National Era:

“Excitement in Baltimore” in The National Era. Aug, 4, 1853. Washington, D.C. Accessed online on April 3, 2016.

“The Fugitive Law: Resistance and Bloodshed” in The National Era. Sept. 18, 1851. Washington, D.C. Accessed online on April 5, 2016.

“Hon. Charles Sumner’s Lecture: The Anti-Slavery Enterprise. Its Necessity, Practicability, and Dignity” in The National Era. May 31, 1855, Washington, D.C. Accessed online on March 31, 2016.

“Maryland Slaveholders’ Convention” in The National Era. June 16, 1859. Washington, D.C.

“Murder of a Supposed Fugitive” in The National Era. May 6, 1852. Washington, D.C. Accessed online on April 4, 2016.

“Riots in Cities” in The National Era. June 5, 1851. Washington, D.C.

“News of the Week” in The National Era, Dec. 14, 1854. Washington, D.C. Accessed online on April 5, 2016.

African Repository:

“Letter from President Roberts” in African Repository. Oct. 1, 1853. Washington, D.C. XXIX: 10. Page 290.

“Proceedings of the Convention of Free Colored People of the State of Maryland” in African Repository. Sept. 1, 1852. Washington, D.C. XXVIII: 9. Page 259.

Other:

Archives of Maryland Online. Accessed on March 30, 2016.

Baltimore Police Official Website. Accessed online on March 25.

Graham, David A. “The Mysterious Death of Freddie Gray” in The Atlantic. Published online on April 22, 2015. Accessed online on April 1, 2016.

Footnotes

[i] David A Graham. “The Mysterious Death of Freddie Gray” in The Atlantic. Published online on April 22, 2015. Accessed online on April 1, 2016.

[ii] Sam Mitrani. “The Rise of the Chicago Police Department: Class and Conflict, 1850-1894.” Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 2013. Page 19.

[iii] Baltimore Police Official Website. Accessed online on March 25. Some residents of Baltimore were fully aware of the institutional similarities between the new police departments. One article in the Baltimore Sun notes how the new Baltimore police will not be as efficient as the London police for quite some time, although the exceptional morality of the American character means that American cities have a trait “infinitely preferable to the conservatism of the sword,” making the inefficiencies apparent in the police less pressing than in European cities. (“London and Baltimore Police” in The Baltimore Sun. March 31, 1853: 2. Accessed online on April 3, 2016.)

[iv] Antonio Gramsci. “Intellectuals and Education” in “The Antonio Gramsci Reader: Selected Writings 1916-1935.” Edited by David Forgacs. New York City: New York University Press, 1988. Page 307. Gramsci sets up a dialectic between those in society who “willfully consent” to hegemonic rule and those who must be violently coerced to do so.

[v] Archives of Maryland Online. Accessed on March 30, 2016.

[vi] “London and Baltimore Police” in The Baltimore Sun, March 31, 1853: 2.

[vii] David R. Roediger. “The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class.” London and New York: Verso Books, 1991. Pages 108-110.

[viii] “Arming the Police” in The Baltimore Sun, Jan. 27, 1853: 2. Accessed online on April 5, 2016.

[ix] “Arming the Police” in The Baltimore Sun, Jan. 27, 1853: 2.

[x] “Arming the Police” in The Baltimore Sun, Jan. 27, 1853: 2.

[xi] “The City Councils and the New Police System” in The Baltimore Sun, April 11, 1853: 1. Accessed online on April 5, 2016.

[xii] “The City Councils and the New Police System” in The Baltimore Sun, April 11, 1853: 1.

[xiii] “London and Baltimore Police” in The Baltimore Sun, March 31, 1853: 2.

[xiv] Rockman. “Scraping By,” 35. The term “skulk around town” would have been used by irate masters, not those sympathetic to the plight of runaways.

[xv] Alan Dawley. “Class and Community: The Industrial Revolution in Lynn.” Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1976, 2000. Pages 109-110.

[xvi] Rockman, “Scraping By,” 33-35. “The City Councils and the New Police System” in The Baltimore Sun, April 11, 1853: 1.

[xvii] Mitrani. “The Rise of the Chicago Police Department.” 12.

[xviii] Tera Hunter. “To ‘Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors After the Civil War.” Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1997. Page 34. Herbert G. Gutman. “The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom, 1750-1925.” New York: Pantheon Books, 1976. Page 387.

[xix] “The Fugitive Law: Resistance and Bloodshed” in The National Era, Sept. 18, 1851. Washington, D.C. Accessed online on April 5, 2016.

[xx] “News of the Week” in The National Era, Dec. 14, 1854. Washington, D.C. Accessed online on April 5, 2016.

[xxi] “Look Out for the Slave-Catchers, to the Editor of the N. Y. Tribune Sir” in Frederick Douglass’ Paper, Page [1], Vol. VIII, Issue 13. March 16, 1855. Rochester, New York. Accessed online on April 3, 2016.

[xxii] “Slave Stampedes in Maryland,” Frederick Douglass’ Paper, Page [3], Volume XI, Issue 41. Sept. 24, 1858. Rochester, New York. Accessed online on April 7, 2016.

[xxiii] “Maryland Slaveholders’ Convention,” in The National Era, June 16, 1859. Washington, D.C.

[xxiv] “Letter from President Roberts” in African Repository. Oct. 1, 1853. Washington DC. XXIX: 10. Page 290.

[xxv] “Proceedings of the Convention of Free Colored People of the State of Maryland” in African Repository. Sept. 1, 1852. Washington, D.C. XXVIII: 9. Page 259.

[xxvi] “Hon. Charles Sumner’s Lecture: The Anti-Slavery Enterprise. Its Necessity, Practicability, and Dignity” in The National Era, May 31, 1855. Washington, D.C. Accessed online on March 31, 2016. All current police officers reading this should take note of this fine example.

[xxvii] Douglas A. Blackmon. “Slavery By Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black People in America from the Civil War to World War II.” New York: Doubleday Books, 2008.

[xxviii] The classic protest chant, resurrected most recently by Black Lives Matter, is of relevance here: “Who’s streets? Our streets!”

[xxix] Rockman. “Scraping By.” 43.

[xxx] Bryan Wagner. “Disturbing the Peace: Black Culture and the Police Power after Slavery,” Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2009.

Duncan Tarr, an abolitionist living in the Rustbelt, can be reached at duncan.tarr@gmail.com.