by Bill Quigley

Reports of the deaths caused by the collapse of the school on Friday continue to climb, reaching nearly 100 on Sunday. Several hundred other children escaped or were rescued. Many are still missing.

“The families of the victims are mad,” the father said. “But it is not just the families who are mad. All the people know the government is not making good decisions. We do not trust that the government will help us. No doctors have come. Nobody comes except those who want to take pictures, make reports, and make money. We have been promised everything, but we have received nothing.

“Watch,” he said. “After 15 days, no one is even going to be talking about this. Only the victims and the families will be talking about it. The government and some other people will get some money out of the disaster, and the children and their families and the community will see none of it.”

Haiti has been plagued by a string of disasters this year with over 800 dead from four hurricanes that raked the island nation; many of those dead were also children.

The three-story school which collapsed, College La Promesse, has for years served hundreds of children from pre-school through high school, ages 3 to 20. The school operated on a hillside in Petionville, a suburb of Port au Prince.

One 8-year-old girl, who had attended the school for three years, reported that her class had just returned from recess when they saw the ceiling in their classroom falling down. She told this writer that she prayed to God to save her and started running but could not see because of all the dust and smoke in the air.

“I tried to get out. I heard the building breaking down. I was crying and I ran away. A man teacher grabbed my hand and pulled me out of the school as the whole building was falling. After I got outside, the teacher went back in. I cried and cried because I could not find my brother and sister.” The little girl eventually found her family and her brother and sister were not seriously harmed.

“When I try to sleep,” said the little girl, “I fear the house is going to fall on me and I see the school falling again.” She has bruises on her leg and stomach. Some friends are still missing.

Rev. Fortin Augustin, founder and operator of the school, was being held and questioned by Haitian authorities over the weekend. Family members of Rev. Augustin said he voluntarily turned himself in Saturday after receiving numerous threats against himself and his family.

Though the government is reportedly considering charging Rev. Augustin with involuntary manslaughter, relatives think he is being blamed for common construction problems in Haiti. The Reverend had his own two daughters in school that day, said a nephew, who brought the injured children for medical treatment. Family members taught there. And for years all his nieces and nephews attended the school.

His nephew, who brought food to him on Sunday morning, said that his uncle did not even know that two of his little cousins died in the collapse. “He cried when I told him that,” he said. “The family understands why people are angry,” the nephew reported,” but this was a family church and a family low-budget school. They were just trying to help the community.”

One parent agreed. “I do not think it is the Reverend’s fault,” he said. “This is all about the government. They allow any type of construction anywhere. Many schools and other buildings in this country are built the same way. Why didn’t the mayor stop the school construction if it was wrong? The mayor campaigned in this very school and in the church. I accuse the government – the mayor, the ministers, even President Preval.”

Haiti is the most impoverished country in the Western Hemisphere. Over half the population – over 4 million people – lives on less than $1 per day and over three-quarters – over 6 million – live on less than $2 a day. Meanwhile, Haiti is forced to send over $1 million a week to repay off its foreign debt, over half of which was incurred when the country was ruled by dictators friendly with the U.S. The 7,000 U.N. troops in Haiti cost over $1 million each day.

When asked if the parents considered going to court to seek justice from the government, the father scoffed. “Justice in courts in Haiti exists only for the people in the government and the people with money. When you are poor, your justice is in the Bible and in Jesus alone.” The parent asked that his name not be used for fear of reprisal. “Everyone knows this is the truth, but in Haiti you can be killed for telling the truth.”

The father saw hope in the U.S. presidential election last week. “Maybe now that Obama is president of the U.S. he can put some pressure on Haiti to do good for the people. Obama is a hope not just for the U.S. but for all America. There are many countries in America, including Haiti. We hope he will be a leader of all the Americas and can help.”

Pere Jean-Juste admits the current situation is grim but also sounds a note of hope. “We can provide for the basic needs of the poor in Haiti,” he promised. “We cannot continue to just apply bandage solutions to various emergencies while other major catastrophic threats remain over our heads in Haiti.

“No more bloody coup d’etats, no more privatization of public institutions, no more violations of human rights. We can build a new Haiti. All together, with or without support from our allies, yes we can.”

Bill Quigley is a law professor and human rights lawyer at Loyola University New Orleans. Bill has visited Haiti many times as a volunteer advocate with the Institute for Justice and Peace in Haiti, www.ijdh.org. Vladmir Laguerre, a journalist in Port au Prince, helped with this article. Bill can be reached at quigley77@yahoo.com.

‘Fewer tanks and more tractors’

by Marguerite Laurent

When he first took office in 2006, President Rene Preval said that Haiti needs technical assistance, tractors and bulldozers, not tanks and war machinery.

On Friday, Nov. 7, a church school collapsed in Petionville, Haiti, with hundreds of children buried beneath the rubble and there is no crane, bulldozer, special electronic guiding equipment – no heavy search and rescue equipment to get those still trapped out.

The AP wrote, “While Haitian President Rene Preval has called on the [U.N.] force for more than two years to provide long-term assistance with ‘fewer tanks and more tractors,’ U.N. Special Representative Hedi Annabi said he would not request a shift to development work this year because it is not the council’s mission.

“‘I’m not going to ask for something that will never happen,’ Annabi told The Associated Press.”

If MINUSTAH (United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti) is not in Haiti to help with what the people actually NEED and to help in the case of emergencies like the school collapse, then why are 9,000 of them there? What use are they to the people of Haiti?

“Today if Haiti had more bulldozers, more children would have been rescued. One boy was trapped by debris that pinned his legs beneath the rubble. He begged the rescuers to ‘please cut my feet off,'” a firefighter told Reuters.

“At the scene, crying and screaming parents searched desperately for their children while bodies of students lay crushed under blocks of concrete.”

Mothers of the school children and neighbors who live around the school that our Haiti correspondents spoke to late yesterday evening say the screams and moans of more students, buried in the rubble of the concrete building, could still be heard throughout Friday night, the day of the collapse. Our HLLN correspondents in Haiti assisting the neighbors and families with the rescue efforts put their cell phones next to the wreckage to have our network listen to the buried children’s desperate cries for rescue in the fallen darkness.

By the time international rescue teams arrived from Martinique and Virginia with floodlights and with search dogs wearing huge “USAID” signs around their torso for the requisite publicity shots, by the time trucks carried oxygen and medical supplies down the mountain road, by the time international rescue teams arrived to help on Saturday, the day after the collapse, it was too late. The crane, sonar, cameras and USAID rescue dogs were too late. Only four survivors – two girls, ages 3 and 5, and two boys, a 7-year-old and a teenager – were pulled alive from the ruins on Saturday, and no other survivors have been found since.

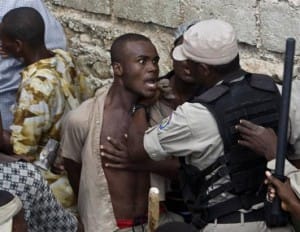

Parents and the good Samaritans who had found so many of the children before the special teams arrived wanted to be allowed to resume searching because they did not feel the rescue teams were working hard enough to find their children. Anger and frustration over the slow pace of the rescue effort boiled over on Sunday afternoon, when hundreds of people rushed the wreckage and began trying to pull down the massive concrete slab.

Thousands of onlookers cheered them before Haitian police and U.N. peacekeepers drove them back with batons and riot shields. “They threw rocks at police and U.N. peacekeepers demanding they be allowed to help speed up the rescue process. The situation was calmer Monday as more locals were given jobs participating in the search.”

Second Haiti school collapse injures nine

“A Port-au-Prince school partly collapsed Wednesday, days after more than 90 were killed in another school cave-in, sparking a panic among parents of children in other risky schools and street protests over dangerous buildings,” AFP reported.

“Nine people were injured when walls at the small Grace Divine school in central Port-au-Prince partly gave way and the ceiling began to fall in, police said.”

If the U.N. had answered President Preval’s call, made in 2006, then today, in 2008 during these tragedies, Haitians would have some rescue equipment, some bulldozers, some tractors. They would not be using bare hands and hand tools to get to the school children trapped beneath the crumbled concrete.

Marguerite Laurent, an award winning playwright, performance poet, dancer, actor and activist attorney born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, founded and chairs the Haitian Lawyers Leadership Network, supporting and working cooperatively with Haitian freedom fighters and grassroots organizations promoting the civil, human and cultural rights of Haitians at home and abroad. Visit her website at www.margueritelaurent.com.