by Charlie Hinton

However, he soon announced that he will sue to get on the ballot, providing the next episode for Haiti’s ongoing presidential election soap opera.

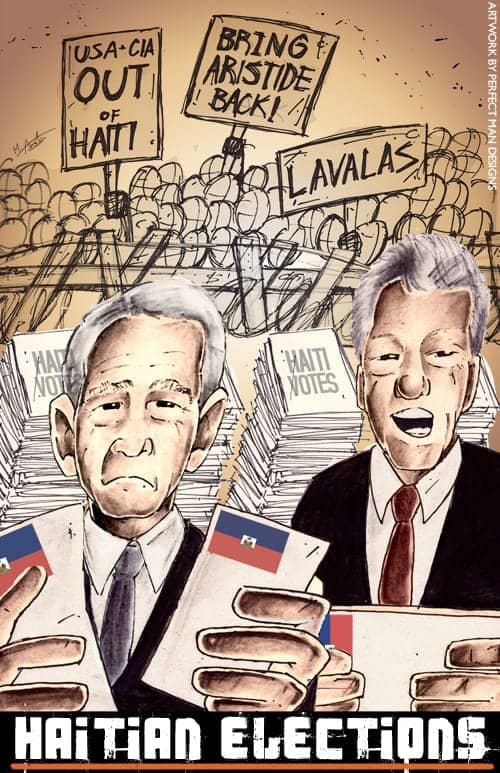

And the election does go on. Even though Haiti lives under military occupation with more than 11,500 uniformed U.N. personnel on the ground, both military and police; even though the earthquake destroyed most election registration records; even though more than a million people remain living in squalid tent and tarp encampments in Port au Prince and points south and would miraculously have to be re-registered in 90 days; even though the money that will be spent on this election could feed and house thousands of these Haitians in extreme need; even though the president’s term has been extended on an emergency basis, despite widespread protest; even though the largest and most popular party, Fanmi Lavalas, has been excluded from running candidates and its leader, twice overthrown President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, continues to be banished from returning to Haiti; even though the “international community” has supported dictators and tyrants throughout Haiti’s history, including the murderous Duvalier family, these elections go on.

Why? There’s a term for it. Instead of holding a free and fair election, where all parties, candidates and voters openly participate, this is a “demonstration election.”

In the case of Haiti, Fanmi Lavalas and the Lavalas movement have overwhelmingly demonstrated their popularity and influence in every election since 1990, when Aristide was elected with 67 percent of the vote. The Haitian majority loves President Aristide. He said he wanted to raise Haitians from a state of misery to “poverty with dignity,” and he practiced what he preached, building schools, parks, housing, hospitals and clinics, and a medical school, despite having his government starved of funds and loans, because he put the needs of poor Haitians ahead of the demands of international bankers (see http://haitisolidarity.net/downloads/We_Will_Not_Forget_2010.pdf).

With the Electoral Council banning candidates from Fanmi Lavalas, we are presented with an election, in the name of “democracy,” where the most popular party in the country is prevented from participating – providing the illusion of electoral “democracy” as a front for a military occupation whose goal is to repress the forces calling for the democratic sharing of power and wealth in the first place – the precise definition of a “demonstration election.”

The Haitian majority loves President Aristide because he put the needs of poor Haitians ahead of the demands of international bankers.

After the United States conquered Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines in 1898, the powers that be decided to create an “informal empire” as a means of control, rather than the kind of direct colonial occupation that the European powers had used in their conquests of Africa, Asia and the Middle East. The U.S. would use elections during an occupation to legitimate its preferred candidate, then use economics and other means of coercion to maintain a loosely knit system of neo-colonial dependency.

A demonstration election is a media event above all else. The media sell the election to taxpayers at home to show “progress” and justify spending the money for the occupation. They feature the election as BIG NEWS, when it’s really propaganda, a smokescreen for the harsh realities on the ground.

That is why the candidacy of Wyclef Jean is so important – it makes this Haitian election a media “event” and gives it the illusion of credibility, when its real goal is to suppress the Lavalas movement, put a democratic front on a brutal military occupation, install a friendly face who will obey the will of the “international community” investor class, and continue the neo-liberal economic direction of the current Haitian government, all the while presenting the face of “democracy” to the outside world.

So now we have 19, possibly 20, candidates lined up, most of them with a tiny or no constituency, and all willing to play ball with the forces of occupation, while Lavalas supporters demonstrate to denounce the elections as a fraud, and U.N. troops shoot up the neighborhoods where they live.

But the media will never report on this. They have “on-agenda” items – basically anything about Wyclef – and “off-agenda” items – basically everything else, but especially any analysis of the background, context and Real Purpose of the election and, in the case of Haiti, that the Lavalas movement even exists. But it does. Stay tuned.

Charlie Hinton is a member of the Haiti Action Committee (http://haitiaction.net/ and http://www.haitisolidarity.net/) and works at Inkworks Press, a worker owned and managed printing company in Berkeley. He may be reached at ch_lifewish@yahoo.com.