by Mark Schuller

“Of course it is. But you know I have a house.”

“We are all wet!” he intoned. “We won’t get to sleep tonight.”

I doubt if I will either. It’s been raining – hard – since this afternoon. There’s a tropical storm brewing northeast of Hispaniola, creating a 60 percent chance of several rainy days.

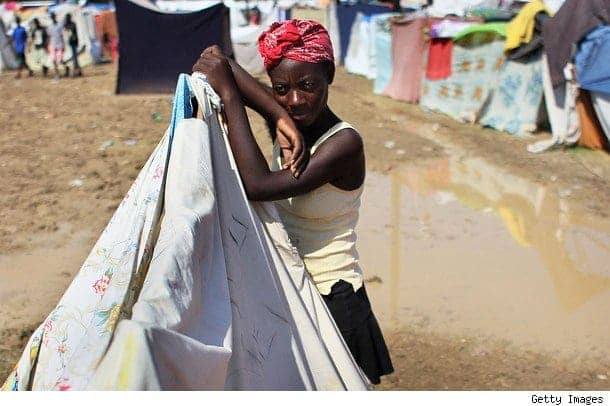

Now more than six months after the earthquake, the 1.5 million homeless that it created are still waiting for change to come. True, some 28,000 people are living in 5,657 “T-shelters” (temporary shelters). But hundreds of thousands of families are at this very moment desperately trying to keep things dry: important documents, money, baby photos or babies themselves. I’ve been to camps where as many as half of the tents are now ripped.

July 12 marked the six-month point following the earthquake. At the National Palace’s remains, medals were given out to several people, including CNN journalist Anderson Cooper and actor Sean Penn, who has been managing a camp for internally displaced people. The French ambassador joked that it was important to acknowledge the powerful neighbor to the north, as no French citizen or group – or, for that matter, Cuban or Venezuelan – received a medal.

That afternoon, a rainstorm wreaked havoc on the Corail camp, held up as a model. Hundreds of tents were instantly destroyed, and a couple of thousand people rushed under the shelter of the tent donated by the Cirque du Soleil. People were moved from the camp where Penn is now working because of the “environmental” risks – to wit, flooding following a rain storm.

True, Corail boasts many services that many (if not most) other camps lack: latrines, showers, wash water stations, a medical clinic, and even a “Krik Krak” library donated by Haitian-American writer Edwidge Danticat. But Corail’s flooding as the Haitian government knighted foreigners is emblematic of deeper issues that require urgent and sustained attention.

First, the camp is isolated. On public transportation, it takes an hour and a half to get to town, using three or four buses, depending on routes. There are no markets, no stores, no schools, not even a church in or near the camp. It is built near Titanyen, the mass burial ground used by paramilitaries in the past and by the current government to bury the quake’s unnamed dead in unmarked graves.

Not just bereft of economic activity, the area around Corail lacks vegetation. It is a desert. The tents sit under a bare mountain. There are no trees to provide shade or to hold the soil, so gusty winds carry white dust into the tents and people’s nostrils. The white rocky ground reflects the brutal Caribbean sun.

“There really is nothing to do,” said a resident who was either afraid or tired of giving her name after scores of journalists have visited the camp. “You can’t stay in your tent because of the heat. You can’t go outside because of the dust. And you can’t leave the camp because there’s nothing to do.” What’s worse, the woman and her 7,000 new neighbors may be forced out yet again to accommodate a new industrial park, although the proposed factories are where Haitian government planners hope people will soon find work.

France, for example, hasn’t paid up – and it vehemently denied a prank that it would pay restitution for the 90 million gold francs Haiti paid its former colonizer from 1825 to 1947 as indemnity. The U.S. has still to pay its $1.15 billion in pledged aid.

Making matters worse, the foreign-led Haiti Interim Reconstruction Commission, co-chaired by U.N. Special Envoy Bill Clinton and Haitian Prime Minister Max Bellerive, is replacing Haiti’s elected government now that Parliament has expired, and it postponed its second meeting scheduled for July 22 by a month.

Haiti had some very promising opportunities following the earthquake. First was general goodwill and unity. In the days immediately following the quake, people worked across extreme class and political divisions to survive. And they did. As the urgency wore off, the old divisions came back with a vengeance.

For example, on July 21, the Provisional Electoral Commission (CEP) reiterated its 2009 decision to exclude Fanmi Lavalas, the party of exiled former President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, from this year’s legislative and presidential elections postponed from Feb. 28 to Nov. 28, 2010. The U.N. has proclaimed April and June 2009 partial Senate elections, in which almost no one voted because Fanmi Lavalas was excluded, a success.

Another opportunity squandered is decentralization and rural development. Some 600,000 people like Frisline and Marie-Jeanne, two women in the documentary “Poto Mitan” (which I co-directed), left the city to go to the provinces. Haiti’s crumbling rural infrastructure could have been rebuilt by employing tens of thousands. With no jobs, no aid, no prospects of rural development, nothing to keep people in the provinces, the bulk of this reverse migration was undone, and Port-au-Prince is once again a magnet for those seeking jobs.

Hundreds of thousands of homeless are begging for $4.50-a-day (180 gourdes) cash-for-work jobs, mostly to clear the rubble with sledgehammers and wheelbarrows. This is less than the legal minimum wage of $5-a-day (200 gourdes) for non-assembly factory work. Meanwhile, Haiti’s upper class, diaspora vacationers and foreign consultants – some making as much as $1,000 per day – zoom by in new air-conditioned cars. Some foreign aid workers even stay in the Port-au-Prince harbor on two cruise ships – one dubbed the Love Boat – which the U.N. has leased at $112,500 per day, or the price of 100 “T-shelters.”

If the reconstruction aid ever arrives, much of it should go towards a real national development plan, building factories to transform and keep the value of Haitian agricultural produce in the country. For example, yesterday I bought three mangoes for 25 cents (10 gourdes). At a Whole Foods store in New York last month, these same mangoes sold for $2.50 apiece. This “value added” should stay in Haiti, in the peasant, rural sector. But the current development blueprint, the Collier Report – highlighted on the U.N. Special Envoy page – prioritizes export.

These uprootings just contribute to an already insecure existence. Frisline, who is living in her second camp since moving back to Port-au-Prince, lamented: “You never know what’s happening. One day they could ask you to leave. We never know anything. Nothing is secure.” As if to illustrate her lack of security, someone stole her bag with most of her remaining belongings on July 20. Since she lives in a tent, there’s no way to lock up anything.

The rain just stopped, three and a half hours after it began. My phone isn’t ringing. I know I will see and hear more of the damage tomorrow morning. In the meantime, I am honoring a promise to Leslie, Frisline and other people to do what I can to spread the following messages:

• Despite the dip in news – except for the coverage at the sixth-month mark – the majority of Haiti’s people are doing very badly. The situation is still quite urgent.

• The aid needs to be released. Now. The U.S. Congress should vote on this without delay.

• People need shelter. The short-term T-Shelters may do for now but people have a right to housing. They need it desperately since hurricane season continues for several more months.

• The Haitian government needs to protect the 425,000 or so families that are living in camps from forced removal. The best policy is to build permanent housing and provide jobs and services that will give people reasons to willingly leave and to create incentives for private homes to be quickly rehabilitated.

• Haiti needs fair and inclusive elections. Don’t exclude the Fanmi Lavalas and take steps to ensure that the 1.5 million homeless will have access to electoral cards.

These homeless – like Leslie – can’t afford for reconstruction to be postponed any longer.

Mark Schuller is assistant professor of African American Studies and Anthropology at York College, the City University of New York. Having researched NGOs in Haiti since 2001, he is studying the impact of aid on conditions and governance in the IDP camps this summer. He is the co-editor of “Capitalizing on Catastrophe: Neoliberal Strategies in Disaster Reconstruction.” This story originally appeared in Haiti Liberte, and another version was published on the Huffington Post.