by James Ridgeway

First and foremost, the conditions of their release stipulate that Gladys Scott must give Jamie Scott a kidney. From the very beginning of this medical scandal, in which Jamie’s health was further compromised by inadequate prison health care, Gladys offered her kidney for transplant to her sister.

For the governor to mandate this donation is both unprecedented and unconscionable. As others have pointed out, releasing Jamie Scott before she has this costly life-saving surgery could also stand to save the state a considerable amount of money; a donation from her sister could save even more and is apparently part of the price of their freedom.

At the same time, the Scott sisters will have to pay out money to maintain their freedom. Rather than pardoning Jamie and Gladys, Barbour suspended their sentences. According to Nancy Lockhart, a legal advocate who played an instrumental role in the sisters’ release, each will have to pay $52 a month for the administration of their parole in Florida, where their mother lives and where they plan to reside.

Since they were serving life sentences, that means $624 a year for the rest of their lives. Both women are now in their 30s; if they live 40 more years, each will have paid the state $24,960. Of course, Jamie, in particular, will be lucky to live so long.

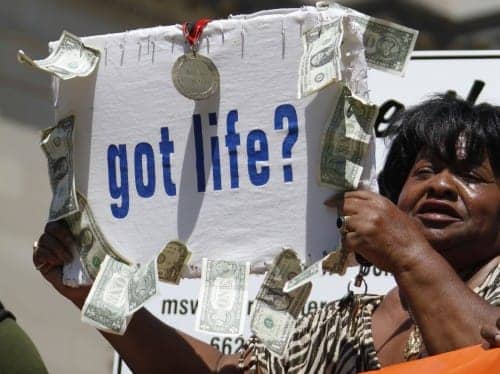

The consequence of failing to pay the fees charged for parole or probation can be a return to prison. As the Southern Center for Human Rights has documented, such fees are part of a larger system that adds up to what are in effect modern day debtor’s prisons:

“Contrary to what many people may believe, there are debtors’ prisons throughout the United States where people are imprisoned because they are too poor to pay fines and fees.

“The United States Supreme Court in Bearden v. Georgia, 461 U.S. 660 (1983), held that courts cannot imprison a person for failure to pay a criminal fine unless the failure to pay was ‘willful.’ However, this constitutional commandment is often ignored.

“Courts impose substantial fines as punishment for petty crimes as well as more serious ones. Besides the fines, the courts are assessing more and more fees to help meet the costs of the ever-increasing size of the criminal justice system: fees for ankle bracelets for monitoring; fees for anger management classes; for drug tests, for crime victims’ funds, for crime laboratories, for court clerks, for legal representation, for various retirement funds, and for private probation companies that do nothing more than collect a check once a month.

This system of imprisonment-by-poverty in turn fits into what author Michelle Alexander, among others, have called “The New Jim Crow” – an America in which mass incarceration has become the new means of wielding control over poor African Americans. For more on how Mississippi and other Southern states have historically used fines and imprisonment to extend the institution of slavery, see Friday’s post on the Prison Culture blog (reposted below).

James Ridgeway is senior Washington correspondent for Mother Jones and also writes for the Guardian and Counterpunch and for Solitary Watch on prison issues. He was Washington correspondent for the Village Voice for 30 years. This story originally appeared on Solitary Watch, athttp://solitarywatch.com/2011/01/07/the-scott-sisters-debt-to-society-and-the-new-jim-crow/. Solitary Watch can be reached by email at solitarywatchnews@gmail.com or write to Solitary Watch News, P.O. Box 11374, Washington, D.C., 20008.

Mississippi’s very terrible, horrible criminal legal history

There are a couple of reasons why I have resisted commenting on the case of the Scott Sisters in Mississippi. The first is that there has been terrific coverage of the case at Solitary Watch. The second is that this case is unfortunately not atypical. In fact, the truth is that the criminal IN-justice system destroys countless lives every single day in every state of this union.

So instead of addressing the Scott Sisters’ case, I thought that folks might be interested in getting a better sense of just how awful Mississippi’s criminal legal system has historically been.

The end of slavery disrupted the South’s main labor supply. Mississippi was ground zero of white supremacy after the Civil War. This was in part because Blacks greatly outnumbered whites in the state. This engendered a fear of a newly empowered “free” Black majority that could claim social, political and perhaps one day economic power. Something had to be done to prevent the rise of the “free” Black man.

Mississippi is the state that gave the country the “Black Codes” after emancipation. As David Oshinsky (1996) writes: “The Mississippi Black Codes were copied, sometimes word for word, by legislators in South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Louisiana and Texas” (p.21).

W.E.B. Dubois described the Black Codes as follows: “The original codes favored by the Southern legislatures were an astonishing affront to emancipation and dealt with vagrancy, apprenticeships, labor contracts, migration, civil and legal rights. In all cases, there was plain and indisputable attempt on the part of the Southern states to make Negroes slaves in everything but name.”

Vagrancy laws were the centerpiece of the Black codes.

According to Oshinsky (1996): “These codes were vigorously enforced. Hundreds of Blacks were arrested and auctioned off to local planters. Others were made to scrub horses, sweep sidewalks, and haul away trash” (p.21).

Prior to the Civil War and well after Emancipation, Mississippi had a reputation as a lawless, “rough justice” state. Duels among white men were common until the late 19th century and the courts had no hold over the population. Mississippi was the epitome of vigilante justice. The convict lease system in Mississippi was brutal and deadly. Oshinsky (1996) quotes the state’s former Attorney General Frank Johnston as saying that convict leasing in Mississippi had produced an “epidemic death rate without the epidemic (p.50).”

It was against this backdrop that Parchman Farm was established in 1901. Below is a description of the farm:

“Parchman’s twenty thousand acres covered forty-six square miles. Just inside the main gate was Front camp, which contained a crude infirmary, a post office, and an administration building where new convicts were processed and issued their prison garb. The men got ‘ring-arounds,’ shirts and pants with horizontal Black and white stripes; the women wore ‘up-and-downs,’ baggy dresses with vertical stripes … The plantation was divided into fifteen field camps, each surrounded by barbed wire and positioned at least a half-mile apart. The camps were segregated only by race and sex. First offenders were caged with incorrigibles, and adults with juveniles, some as young as twelve and thirteen. ‘Feeble-minded’ convicts were everywhere. Parchman housed prisoners like John Brady, an ax-murderer with the mental age of a five-year old, because Mississippi did not recognize ‘idiocy’ and ‘imbecility’ as special categories in its criminal code. The result was a brutal, predatory culture made worse by the prison’s vast and isolated expanse (Oshinsky, pp.137-138).”

The Farm is memorialized in the great blues song “Parchman Farm Blues” written by Bukka White while he was incarcerated there. This is Bukka White’s performance of his most famous song:

Here are the lyrics to the song:

Judge give me life this mornin’, down on old Parchman’s Farm.

Judge give me life this mornin’, down on old Parchman’s Farm.

I wouldn’t hate it so bad, but I miss my wife and my home.

Now, good-bye wife, all you have done gone, all you have done gone.

Well, good-bye wife, all you have done gone.

But I hope someday you will hear my lonesome song.

INSTRUMENTAL

Now, listen you men: I don’t mean no harm, I don’t mean no harm.

Now, listen. You men. I don’t mean no harm.

If you wanna do good, you better stay off old Parchman’s Farm.

You go to work in the mornin’, just the dawn of day,

just the dawn of day.

Go to work in the mornin’, just at the dawn of day.

And at the settin’ of the sun that is when your work is done.

INSTRUMENTAL

I’m down on old Parchman’s Farm, but I sure wanna go back home, Wanna go back home.

I’m down on old Parchman’s Farm, but I sure wanna go back home.

And I hope some day that I will overcome.

Judge give me life this mornin’, down on old Parchman’s Farm.

Judge give me life this mornin’, down on old Parchman’s Farm.

I wouldn’t hate it so bad, but I miss my wife and my home.

It is worth remembering as we decry the current state of affairs in Mississippi that this state – like many others in the U.S. – has a long history of INJUSTICE. The Scott Sisters’ case has to be placed within the context of years of racialized surveillance in a state that has criminalized Black people for generations.

The unnamed writer of this story can be reached at mariame.kaba10@gmail.com and provides this bio: “I have been an anti-violence activist and organizer since my teen years. I recently founded and currently direct a grassroots organization in Chicago dedicated to eradicating youth incarceration. My anti-prison activism is an extension of my work as an anti-violence organizer.” This story originally appeared on Prison Culture, at http://www.usprisonculture.com/blog/2011/01/06/mississippis-very-terrible-horrible-criminal-legal-history/.