by Robert Roth

Only a small number of Haitians – around 20 percent by most estimates – voted in the elections, the smallest percentage in 60 years to participate in any presidential elections in the Americas. Fanmi Lavalas, the party of Aristide and by far the most popular in Haiti, was banned from participation. Why should people vote? It was a “selection,” not an “election,” we were told over and over again.

By the second round on March 20, Haitians had to choose between Martelly or Mirlande Manigat, a right-wing member of Haiti’s tiny elite. One Haitian friend told us, “This is a choice between cholera and typhoid. You cannot make such a choice.”

Yet the bitter taste of the dismal elections could not diminish the joy of “the return.” As the plane carrying President Aristide and his family back from a seven-year forced exile in South Africa approached the Port au Prince airport on March 18, there were about 50 of us in the inner courtyard of his home. A day before, we had watched quietly as dozens of Haitians methodically painted walls, swept the same floors over and over again to make sure they were spotless, and fixed any last remnant of the destruction that took place at this house after the coup on Feb. 29, 2004.

We had heard that President Aristide – called Titid throughout Haiti – would arrive at the airport around noon, but we had gone to the house earlier to avoid the crush. I had come with a dear friend, Pierre Labossiere, representing the work of the Haiti Action Committee. We were both honored and overwhelmed to be there.

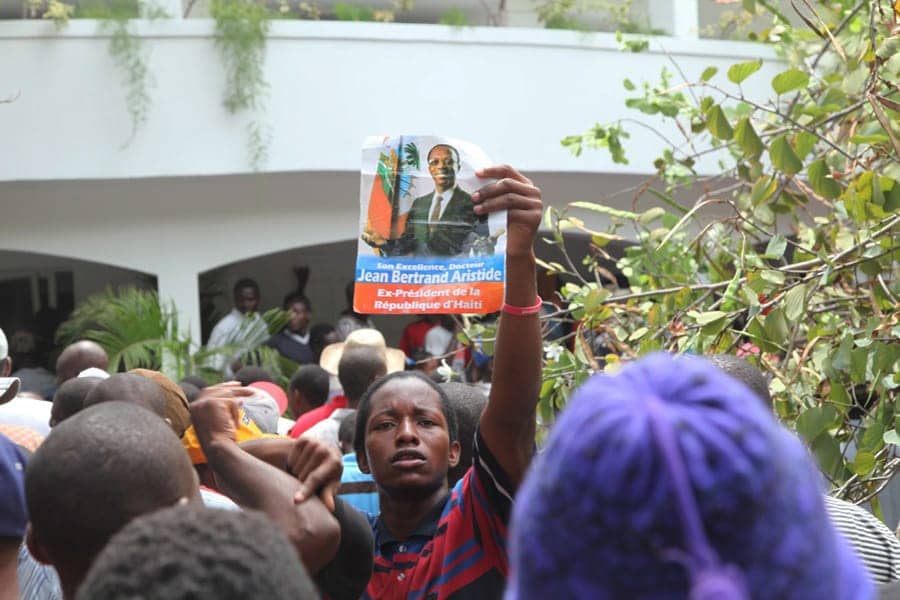

Rumors spread via cell phone: “He’s at the airport, making a speech.” “The car is coming.” We heard a roar. “Lavalas” means “flash flood”: the flood of the poor, who can accomplish wonders when they feel their strength. Thousands were climbing over two sets of walls, rushing past security, engulfing the courtyard. Within minutes, the roofs and trees were filled. There was no room to move.

“Lavalas” means “flash flood”: the flood of the poor, who can accomplish wonders when they feel their strength. Thousands were climbing over two sets of walls, rushing past security, engulfing the courtyard. Within minutes, the roofs and trees were filled. There was no room to move.

Yet in the midst of total chaos, there was discipline and restraint. “Get off the roof,” someone shouted. “It’s Titid’s roof.” “Don’t damage the trees.” Then the singing and the chanting began. “We will not vote in the election. We have no candidate. Welcome back, Titid. Welcome back, schools. Welcome back, hope. Lavalas – we bend, but we do not break.”

We saw another friend, who had been imprisoned during the last terrible years of Duvalier and now lives in one of the internal refugee camps. We asked her, “Are you going into the house?” She said, “No, I can always see the president. It’s more important to hand out water to the people. They are so thirsty.”

I could only imagine the reaction of the U.S. State Department, which tried so hard to stop this moment. President Barack Obama had made a last-minute call to President Zuma of South Africa demanding that he prevent the return until after the new round of presidential elections. What did he think of this scene? Was he even watching?

Finally, it was possible for some of us to get in the house. The people outside stayed and stayed, pressed against the windows – and then left, but not until cleaning the courtyard, picking up what had been dropped.

Mildred Aristide greeted us at the door. “Isn’t it beautiful out there?” she asked.

So many, in and outside of Haiti, had worked for this moment. Not because Aristide is a savior or can solve all the problems in Haiti. Not because his return will end cholera or bring the 1.5 million people out of those terrible earthquake camps. This was a basic issue of justice and self-determination. A democratically elected president had been illegally removed from office and banished from his homeland – and the majority of Haitians never accepted his removal. They wanted him home.

Why? Under Lavalas administrations, more schools were built than in the entire history of Haiti. The government opened 20,000 adult literacy centers, prioritizing the education of women. Health clinics sprang up in remote rural areas. A powerful AIDS treatment and prevention program was launched. The hated military was disbanded. The minimum wage doubled.

The tiny group of rich people who have run Haiti forever were actually asked to pay taxes – and, if they didn’t, their names were read over the radio. The Aristide administration demanded restitution from France for the $21.7 billion that France had extorted from Haiti as its price for Haiti’s abolition of slavery. With the first payment on this debt in 1830, Haiti had to close its public school system. Aristide raised the issue forcefully in 2003 and said that justice should be done.

Slowly, even as the Bush administration blocked needed loans, financed an elite opposition and organized paramilitary operations against the government, Aristide was fulfilling his promise to move the nation from “misery to poverty with dignity.” It was a start, but an historic one.

As reported in Randall Robinson’s book, “An Unbroken Agony,” his wife, Hazel Robinson, looked out at the crowd and commented on the power of the scene to the OAS ambassador sitting next to her. “Well, he does not have the support of the real people,” the OAS official responded. “He has 80 to 90 percent, but they’re not the ones that matter.”

For the U.S. government, these Haitians didn’t matter. Unable to manufacture an “uprising” against Aristide, the United States took direct action on Feb. 29, swooping in special operations forces and kidnapping – yes, that is the word Haitians use to describe what happened – the president and his wife, Mildred, taking them on a long journey to the desolate French neo-colony of the Central African Republic. The long exile had begun.

So many, in and outside of Haiti, had worked for this moment. Not because Aristide is a savior or can solve all the problems in Haiti. Not because his return will end cholera or bring the 1.5 million people out of those terrible earthquake camps. This was a basic issue of justice and self-determination. A democratically elected president had been illegally removed from office and banished from his homeland – and the majority of Haitians never accepted his removal. They wanted him home.

Haiti solidarity activists denounced the coup. We demonstrated, educated and organized, attempting to counter the drumbeat of lies about Aristide, the myth of his “resignation,” the notion that “popular upheaval” had overthrown him. We raised funds to support organizers who were now in grave danger. And we sent delegations to Haiti to learn from Haitians whose powerful voices had been silenced and dismissed on the international level.

Visiting Haiti in late June of 2004, we watched as the United Nations force, MINUSTAH, headed by the government of Brazil, took over the military occupation of the country from the troops of the U.S., France and Canada. Now it was a multilateral operation, like Iraq, like Afghanistan – with the imprimatur of the United Nations. A “peacekeeping force,” we were told.

Yet the people we met said the U.N. soldiers were disrespectful and, at times, brutal – blue helmeted soldiers pointing guns. We saw hundreds of political prisoners locked up in overcrowded cells with no water. We talked to people whose houses had been burned in the Central Plateau. We saw schools that had been destroyed, clinics ransacked, the Medical School at the Aristide Foundation taken over by U.N. troops and 247 medical students forced to flee their campus. And we saw demonstrations – small ones in such a dangerous time – demanding the release of political prisoners.

Father Gerard Jean-Juste, a legendary fighter for human rights in Haiti, was still there, feeding children at his church in St. Claire. He told us, “I receive many death threats. But I will not leave Haiti. I left under Duvalier, but they will not force me out again.” He would later be arrested and beaten in a church, and then imprisoned – released only after developing the leukemia that would lead to his death in 2009.

From 2004-2006, MINUSTAH, in coordination with Haiti’s coup government, launched search and destroy operations to root out Lavalas bases in Port au Prince and the surrounding areas. According to a study published in The Lancet, over 8,000 deaths and 35,000 rapes – many thousands committed by security forces – occurred during this period.

The presidential election of 2006 was held under foreign military occupation. When Rene Preval, who had been a Lavalas president after Aristide, entered the campaign, the base of Lavalas swept him into office. They believed that Preval would bring back Aristide, would free the political prisoners, and develop new economic and social initiatives for the poor.

Not much changed. Preval had developed strong ties to the United States and the U.N. He had no interest in bringing back Aristide and moved to deepen the structural adjustment programs – privatization of the telephone company, new contracts for elite import-export barons, reduced social investment – demanded by the international authorities and the Haitian elite. The price of rice and gas soared. There were more raids into Cite Soleil. The U.S. State Department proclaimed that Haiti was “more stable.”

When we returned to Haiti in 2007, many Lavalas organizers were through with Preval. They said it plainly: “He’s in the arms of the Americans, he does their bidding.” He had broken all communication with the base that elected him. Aristide had always talked to the people – and had always listened.

During our visit, we spent days with Lovinsky Pierre-Antoine, a psychologist, Lavalas leader and human rights activist. At a demonstration in front of U.N. headquarters, he spoke on a small bullhorn while French and U.S. military personnel took pictures of him and the other protestors. He called for a halt to privatization, an end to the U.N. occupation and the return of President Aristide. Two weeks later, Lovinsky was kidnapped and disappeared. Preval said nothing. The U.N. was silent. There was no investigation.

By 2009, the Preval government had lost any legitimacy among the poor in Haiti. As the cost of food spiraled upward, thousands of Haitians marched on the Presidential Palace. “Food riots,” the press called them.

Then the earthquake hit. We saw the terrifying images of destruction, the 300,000 dead, the unbearable conditions in the camps, the courage and dignity with which Haitians faced the impossible. Haiti touched hearts around the world. But a devastating Haitian tragedy presented opportunity for others. NGOs descended. Bill Clinton and George Bush announced a joint fund and visited the country. The U.S. took charge of the “reconstruction.”

When we returned to Haiti in 2007, many Lavalas organizers were through with Preval. They said it plainly: “He’s in the arms of the Americans, he does their bidding.” He had broken all communication with the base that elected him. Aristide had always talked to the people – and had always listened.

Five months later, Haiti looked as if the quake had hit the day before. We met with people in two different camps. They spoke with urgency: “We have received no aid from the United Nations or the Red Cross since March.” “We need food.” “We need work.” “The NGOs pay themselves and give us nothing.” “Preval does not care for us.” “Bill Clinton is not our president.” “Titid must come home.”

The Aristide Foundation, created in 1996 as a center for grass roots social, educational and economic development, was buzzing with activity. With no government or NGO assistance, the foundation was doing what it could: setting up mobile health clinics and schools in the refugee camps, training mental health workers to provide “relief for the spirit.”

Young educators and activists told us that their generation was “motivated,” that they would do anything for Haiti. Fifteen hundred people – three quarters of them women – packed into the foundation’s main auditorium for a “Democratic Debate.” Women in and out of the foundation had passed around a petition to Barack and Michelle Obama calling for Aristide’s return and, within days, 20,000 women had signed it. Ten thousand Haitians took to the streets in Port au Prince on July 15, Aristide’s birthday. The time had come.

Now Aristide has returned, in defiance of the United States – brought home by his people and a determined international campaign.

The task is daunting. Barred from elections, Lavalas has no representatives in the legislature and will have no official power within the state. Partnering with the Haitian elite, the U.S. is setting up sweatshops in the Port au Prince area and preparing to dig up the country’s mineral wealth. Bill Clinton co-chairs an ongoing Interim Haiti Recovery Commission, sitting on over $10 billion. U.S. AID pours money into U.S.-based NGOs that pay more for staff than for projects.

Thirteen thousand U.N. soldiers and police maintain a seemingly permanent foreign occupation. Cholera – introduced to Haiti by U.N. forces from Nepal – has spread. A Harvard-UCSF study now predicts 800,000 cases. Martelly plans to reestablish the military and sharpen the attack on Lavalas. And his compatriot, Duvalier, is there – a spectre haunting the country anew.

Still, the return means so much. The fundamental goal of coups and counter-insurgency is to sever the connection between a popular movement and the people, to destroy even the belief that transformative social change is possible.

At Aristide’s house, in the streets of Port au Prince, it was clear that the coup and occupation have not been able to do this. Fueled by a hard-won victory, grass roots organizers – who have never stopped their work – have already taken heart. There will be powerful initiatives in education and health care and the steady incorporation of a new generation into a movement that has bent but not broken. And a trusted voice of the poor is now back, whatever may come.

In his speech at the airport, as he and his family re-touched Haitian soil, Aristide commented on the undemocratic and exclusionary elections. He focused on the need to include everyone in the life of the country: “Every Haitian without exception, because every person is a human being, so the vote of every person counts.”

Visiting friends and family in New York a short time after returning from Haiti, I had a chance to meet with Haitian community organizers in Brooklyn. I asked one woman, now an assistant teacher in a second grade class, why she had joined Lavalas. What struck her, she said, was Aristide’s slogan, “Tout moun se moun.” She translated it as, “Every one, each person counts.” And she said, “I am filled with joy that he is back home.”

Robert Roth is an educator and co-founder of the Haiti Action Committee. He is also on the board of the Haiti Emergency Relief Fund.