by Lubangi Muniania

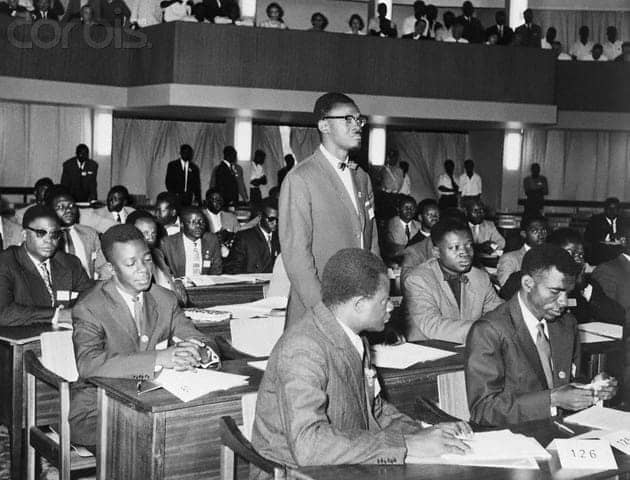

Patrice Emery Lumumba’s party won 41 seats out of 137. After the failure of every maneuver to delay the democratic process, Mr. Lumumba was elected prime minister while Joseph Kasa-Vubu became the president. The Congo became an independent nation on June 30, 1960.

Mr. Lumumba marked the day with a powerful speech before the Belgian king and the newly elected Congolese Parliament. In it he came back to what he had often proclaimed to African audiences, to what was in reality the continent of his childhood memories: the miserable poverty of the colonized peasants and the violence of the colonizer.

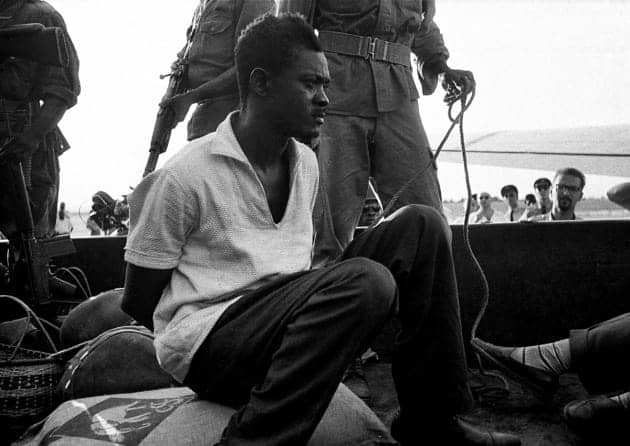

His very short period of office as prime minister was an endless calvary. On a daily basis he faced multiple Western manipulations – the incursion of Belgian troops, the rupture of the country’s diplomatic relations with the former colonial power, the mutiny of the national army, the secession of two strategically important mining provinces, Katanga and South Kasai, ethnic and regional tensions all over the country, economic and administrative disasters, the inefficient and improper intervention of United Nations troops – in short, conflicts resulting from the cold war.

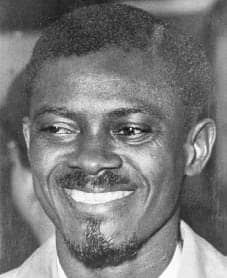

Contrary to popular belief, Lumumba cultivated simplicity and humility more than even legitimate ambition and pride. He was convinced of his mission in the Congo and in Africa generally, and he embraced his fate with an awareness of being a hero – martyr of both the Congolese and the African causes.

“I am in a bad position,” he told journalist P. Scholl-Latour, while already under house arrest. “I will maybe have to die for the unity and the independence of my nation. I will maybe have to render a last and great service to the Congo by sacrificing my life. Africa needs martyrs.”

In his last conversation with his minister of foreign affairs Thomas Kanza, he seemed haunted by the same premonitory idea of death and sacrifice: “One of us must sacrifice himself if the Congolese people are to understand and accept the ideal for which we are fighting. My death will hasten the Congo’s liberation and will help us get rid of the imperialist and colonial yoke” (William 1990:437).

Needless to say, since Lumumba was assassinated Jan. 17, 1961, history has spoken, even when intertwined with passions and myths: The son of Africa, Lumumba, is an “idea.” INGETA, INGETA, INGETA!

Lubangi Muniania is an art educator, specializing in the visual and performing arts of Africa. He has worked as director of education at the Museum for African Art in New York, as African art education consultant for the Art Institute of Chicago, and at the Saint Louis Museum of Arts, other museums, festivals and cultural centers. Muniania is currently the president of Tabilulu Productions. He has also produced documentaries and educational events for Harvard, Yale and Columbia universities, City College of New York, United Nations, Africa-America Institute, Session at West 54 for Sony, Africa One for AT&T, African Portrait for NBC, Memories of Lumumba for the Museum for African Art, radio programs and a documentary on the Democratic Republic of Congo for Bill Moyers Journal at PBS. Muniania can be reached at tabiluluproductions@hotmail.com.

Break the silence! Become a friend of the Congo; go to http://www.friendsofthecongo.org/action.

http://youtu.be/IrbCOol_VVE

http://youtu.be/juanS6VqAjg

http://youtu.be/4X5VasNKNCQ

http://youtu.be/OMv07zw1ZmA

http://youtu.be/bjx6JiD0a3A

http://youtu.be/F9qgibqSzuU

http://youtu.be/1qQHFcpxck8

http://youtu.be/oNE_Pca4I5o

http://youtu.be/HBIBh8iivxk