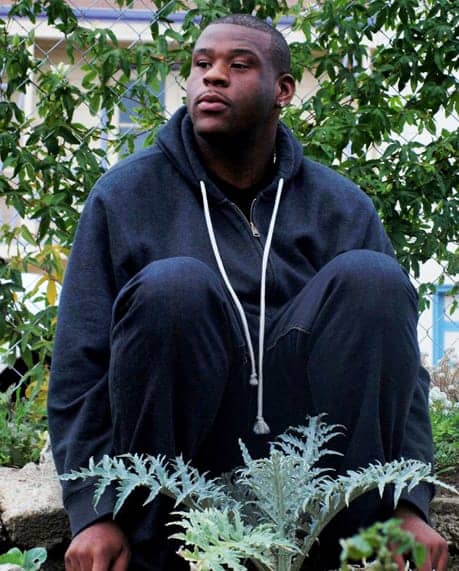

by Kenneth Hill for the Food Guardians

As I sat and waited for my computer to load the next page, my mind began to explore the different possibilities as to why Black farmers were being paid $1.15 in settlements. As I began to read, my eyes and mind consumed the article, reading every word, as it excited my curiosity. As I read further, a sense of gratitude came over me as I learned that the U.S. government had awarded Black farmers $1.15 billion on the basis of discrimination.

My sense of gratitude stemmed from the always controversial topic of reparations for African-Americans. As an African-American who supports the idea of reparations, I believe that the U.S. government’s actions are just, timely and needed. In this case, the government has recognized its faults in a reasonable time, provided more than an apology for their unethical actions, and is giving Black famers that which is overdue to them.

This historic civil rights class-action suit has validated the claims made by Black farmers for decades: that Black farmers were systematically denied USDA loans and farm subsidies that were made available to white farmers with similar credit histories. USDA farm loans and subsidies are an essential part of a farmer’s operating budget and safety net, and this systematic denial of equal rights has resulted in a decline of Black farmers at more than three times the rate of white farmers. Black farmers now make up only 1 percent of the nation’s farmers.

In 1999, Timothy Pigford made a claim of discrimination against the U.S. Department of Agriculture, stating that he was denied U.S. farming money because he is Black. After being denied U.S. Agricultural funds, he joined with other Black farmers in a class action suit, Pigford v. Glickman. The suit claimed that the U.S. Department of Agriculture discriminated against Black farmers and failed to properly investigate the claims of discrimination.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture only owned up to their faults through an approved settlement agreement and consent decree in Pigford v. Glickman on April 14, 1999, by Judge Paul L. Friedman of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. Judge Friedman’s actions were just; however, his just actions were cut short. Not all Black farmers were granted money in this settlement.

These African-American farmers kept fighting until they eventually got justice. Thousands of African-American farmers claimed they did not receive adequate representation, which resulted in delays while filing their claims. The settlement agreement imposed by Judge Friedman on behalf of the U.S. government deemed 22,721 farmers eligible and set the deadline of Sept. 12, 2000, for submitting applications.

By November 2010, 15,642 of the 22,721 eligible class members had received an approval from the courts to be paid. The other 7,079 eligible class members were those who claimed inadequate representation, in addition to thousands of farmers deemed ineligible and others who were unaware of the proceedings in the initial Pigford claim.

But in due time, as America was preparing to elect the nation’s first African-American president, the U.S. government approved a provision in the 2008 Farm Bill that set aside money for African-American farmers who “Farmed or attempted to farm between January 1, 1981, and December 31, 1996; Applied to the USDA during that time period for participating in a federal farm credit or benefit program and believe that they were discriminated against on the basis of race in the USDA’s response to that application; or Filed a discrimination complaint on or before July 1, 1997, regarding the USDA’s treatment of such farm credit or benefit application.” An early estimate from the U.S. government expects more than 70,000 Black farmers to be eligible for funds under the 2008 Farm Bill provision.

“Black people have been bullied out of their way of life for many years, and to see my friends and family made whole is a blessing,” said Isaiah Young. Though some will be made whole, we can’t shy away from reality. The high number of African American communities across the nation impacted by the decline of African American farmers seems to go hand in hand with the lack of access to fruits and vegetables within African American communities.

“Black people have been bullied out of their way of life for many years, and to see my friends and family made whole is a blessing.”

San Francisco’s Bayview Hunters Point, a largely African American district, has deep farming roots, and once played a critical role in the city’s foodshed, according to a report on agriculture and the Bayview by Quesada Gardens Initiative. The Quesada Garden Initiative has compiled a detailed report of Bayview’s history with food and farming, which contrasts with the current lack of access to fruits and vegetables.

The report states that “Bayview Hunters Point is a neighborhood where fresh, healthy food is hard to find, but liquor, fast food and highly processed food and beverages abound.” A lack of fruits and vegetables was not always an issue in Bayview; this report states that “ocean and bay fishing, slaughter houses, rail lines, ‘truck farms,’ pastures for grazing animals and family farms all proliferated here, [in addition to] immigrant families raising animals, vegetables and fruit as part of the community’s daily life.”

But due to many factors, including the redevelopment of the district and the U.S. government’s discrimination against African American farmers, the Bayview, once a farming district, is now saturated with liquor stores and fast food chains. These convenience food outlets sell cheap foods and beverages that are high in salt and sugar, which is a catalyst for the disproportionate rates of diabetes and hypertension that Bayview residents suffer.

In contrast to the fast food chains and liquor stores, the SEFA Food Guardians have been raising awareness by promoting nutrition education and advocating for change, in addition to gathering community input to assuring a lasting change. The Food Guardians raise awareness by educating the community about healthier food options and the importance of eating healthier, as well as linking oppression to these food issues.

The high number of African American communities across the nation impacted by the decline of African American farmers seems to go hand in hand with the lack of access to fruits and vegetables within African American communities.

The Food Guardians also advocate for change by attending many health fairs and meetings, advocating for progressive public policy and utilizing community input to create sustainable change. Creating sustainable change is important to the Food Guardians and essential to the growth of the African-American community.

In an attempt to insure sustainable change, on Dec. 8, 2010, President Obama signed legislation that renders $1.15 billion in damages to African American farmers on the basis of discrimination. On Sept. 1, 2011, the litigation came to an end and the $1.15 billion was approved for payout. U.S. District Court Judge Paul Friedman deemed this settlement to be “fair, adequate, and reasonable.” We now need to work together to fight for access to healthier foods and healthier neighborhoods that are fair, adequate and reasonable for all.

Contact the Food Guardians through Tracey Patterson, Food Guardian project coordinator, at tpatterson@southeastsf.org or (415) 581-2444.