by Sal Rodriguez

For over 18 years, Graves spent 22 to 24 hours in an 8-by-12-foot cell, with a steel bed, small desk, toilet and a small window. Inside the hearing room was a replica of such a cell that approximates the living conditions of over 80,000 incarcerated individuals. Psychologist Craig Haney testified that “the cells themselves are often scarcely larger than the size of a king sized bed. Prisoners thus eat, sleep and defecate each day in areas just a few feet apart from one another.”

It’s a nightmare scenario I’ve read about for the past year in my work on this issue for Solitary Watch. Again and again, I have received letters from individuals held in isolation units across the country, sometimes for 10, 20 and 30 years describing terrible psychological pain. One individual, isolated for over five years, described daily life as consisting of “reading, writing, crying and begging for death.”

“Solitary confinement does one thing: It breaks a man’s will to live and he ends up deteriorating.”

Federal Bureau of Prisons Director Charles Samuels testified that of the over 218,000 individuals in federal institutions, approximately 7 percent reside in restrictive housing units. Most notorious of these is the ADX Florence facility in Colorado, where the 490 individuals held there are held on average in isolation for over 500 days, many for years. “All inmates in our restrictive housing units have contact with staff, out-of-cell time for recreation and an opportunity to program,” Director Samuels said.

These concerns have been reported by the bipartisan Commission on Safety and Abuse in America’s Prisons, which found that the use of solitary confinement is associated with higher recidivism rates.

The devastating effects of long-term isolation on mental health have been known for a long time. In 1890, Supreme Court Justice Samuel Miller condemned the practice, writing: “A considerable number of the prisoners fell, after even a short confinement, into a semi-fatuous condition, from which it was next to impossible to arouse them, and others became violently insane; others still committed suicide; while those who stood the ordeal better were not generally reformed, and in most cases did not recover sufficient mental activity to be of any subsequent service to the community.”

“This enforced asociality and the virtually total lack of training or meaningful programming that isolated prisoners typically receive can significantly impede their post-prison adjustment, raising important concerns about the effect of solitary confinement on recidivism and public safety.”

Grotesque descriptions of self-mutilation and bizarre behaviors such as coprophagy (eating feces) were testified to in the hearing, and in my own correspondence with supermax inmates such issues are commonly reported. Self-harm often escalates to suicide attempts. According to Sen. Durbin, since 2006 there have been 116 suicides in the federal prison system, 53 of which took place in isolation units.

Mississippi may hold the key to reducing the use of solitary confinement. Mississippi Department of Corrections Commissioner Christopher Epps testified to the dramatic reduction of Unit 32 at Mississippi State Penitentiary, Parchman. In 2007, corrections officials reexamined the criteria by which inmates were placed in “administrative segregation” and determined that the practice was overused. Since 2007, there has been a reduction from over 1,300 to currently 316 incarcerated individuals in administrative segregation, 188 of whom are participating in a program allowing them to transition out of segregation.

“Mentally ill inmates are twice as likely … to be in solitary confinement, 2 1/2 times as likely to receive a sentence in solitary that exceeds their projected release date from prison and over three times as likely to be assigned to an indefinite period of time in solitary.”

There is reason to believe that prisons are overusing solitary. In California, one can be placed in isolation for “possession of five dollars or more without authorization.” In North Carolina, self-mutilation may result in up to 30 days in isolation. In Virginia, there are Rastafarians who have been held in isolation for over a decade for refusing to cut their hair.

It is my hope that this issue finally gets the critical examination and public attention it deserves.

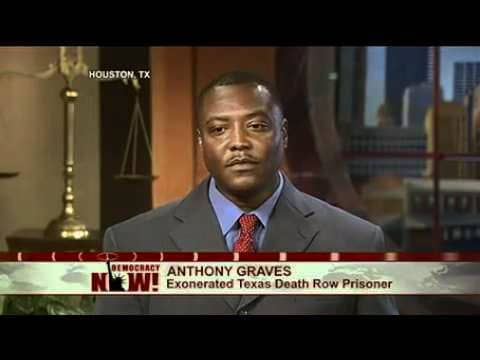

To watch the official Senate video of the entire hearing, click here. Coverage by Democracy Now! and NPR are reposted below.

Sal Rodriguez is a summer intern at the Justice Policy Institute, where this story first appeared, and manages the Solitary Watch blog. Email him at rodrigsa@reed.edu or write to him at Solitary Watch, P.O. Box 11374 , Washington, DC 20008.