by Carol Harvey

On Aug. 1, 2012, following the police shooting of a mentally ill man, San Francisco Police Chief Greg Suhr, like chiefs before him, attempted for the fourth time in a decade – without public notice – to revive the taser debate.

People in crisis appear to have become the rationale for equipping police officers with so-called “non-lethal” tasers in addition to lethal weapons – guns. Chief Suhr’s argument? To stop police firearm murders, we will use “less-lethal” tasers. His rationale seems based on a law enforcement myth: Guns kill! Tasers save lives!

A Police Commission majority led by Angela Chan, citing the unfulfilled stipulations of a resurrected Feb. 23, 2011, resolution, tabled the taser proposal until the requirements are met.

Are tasers truly ‘less lethal’?

According to Amnesty International, since 2001, at least 500 people in the U.S. died from taser shocks during arrests – the largest number, 92, in California.

On Aug. 1, 2012, following the police shooting of a mentally ill man, San Francisco Police Chief Greg Suhr, like chiefs before him, attempted for the fourth time in a decade – without public notice – to revive the taser debate.

During the Aug. 1 Police Commission meeting, Commissioner Petra DeJesus read out Taser International instructions warning against taser use on vulnerable “high risk” populations – “pregnant, infirm, elderly, small child, or low body mass (thin) persons.” Tasers can be fatal to diabetics, people with heart problems and drug users.

Deetje Boler, San Francisco elder, echoed the convictions of Aug. 12, 2012, Police Commission public commenters: “The name ‘less lethal weapons’ is a misnomer. [Tasers] are more lethal because the assumption is made they are not lethal.”

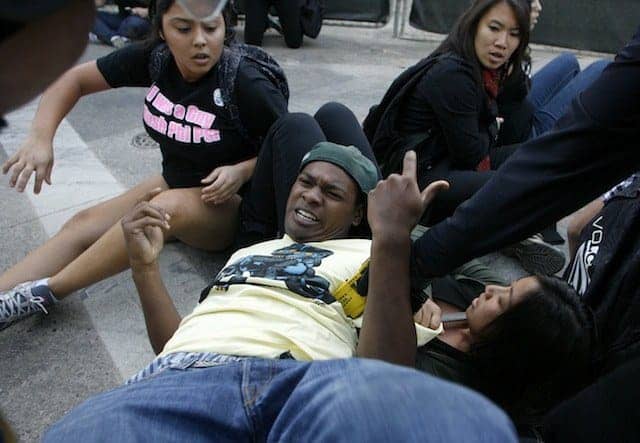

A cursory YouTube survey shows police across America use tasers commonly in low-danger situations or to control mildly non-compliant people, like elderly women or a young girl who wandered into her mother’s arrest.

Concerned citizens acknowledging taser lethality seek to re-direct the SFPD from weaponry to a focus on verbal de-escalation techniques, especially appropriate in talking down people in mental health crisis.

Tasers

Taser International is the main developer and purveyor of electroshock weapons. Tasers, or CEDs, Conducted Energy Devices, employ a gas cartridge to propel pairs of metal darts or copper prongs similar to cattle prods which penetrate clothes, skin and muscles.

Connected by wires to the taser, the probes administer an electric shock, shooting 50,000 volts, more alternating current than the body can handle. This electrical flooding triggers powerful muscle contractions and nerve blockage with momentary neuromuscular paralysis. The victim collapses in intolerable pain.

Before the Aug. 1 San Francisco Police Commission hearing, Clay Winn, Taser International salesman, power-pointed the X-2: “We are a two-darted system – a positive and a negative. I fire the first cartridge; I’d get one dart in him. That is not going to be effective. By firing the second bay, any dart from that other second bay completes the loop with an increase in effectivity and efficiency in dynamic situations.”

The X-2’s new dual laser system has technology telling the officer where the top dart and the bottom dart are going. “We need to get in different muscle groups to take that structure out to prevent that suspect from moving forward,” he said.

Tasered

In 2004, Mesha Monge-Irizarry, whose son, Idriss Stelley, was shot 48 times by San Francisco police during a mental crisis, allowed herself to be tasered in her Idriss Stelley Foundation office, where she counsels bereaved families and loved ones of victims disabled or killed by law enforcement.

She underwent the tasering “to know exactly what our clients may be exposed to.”

“They warned me I may curse, faint, and urinate or defecate on myself.” They did not caution her about possible risk from her diabetes.

“Fifty thousand volts shot through my body!” Pierced by the prong in the right thigh, she collapsed on the floor, unable to move, “in unbelievable pain.”

“The pain disappeared after about 10 seconds. Muscle control was regained. My right leg kept twitching off and on for a couple of days.”

She suffered slight bleeding and bruising and a substantial increase in right leg diabetic peripheral neuropathy. One prong shot in her right hip caused permanent sciatic nerve and conjunctive tissue damage between her right femur and pelvic bone. She walks slowly with a cane.

As they left, “these idiots said, ‘You have balls for a woman.’” She imagined “victims repeatedly tased to unconsciousness or death.”

“Fifty thousand volts shot through my body!” Pierced by the prong in the right thigh, she collapsed on the floor, unable to move, “in unbelievable pain.”

She could have been describing the police tasering torture and death of Andrew Torres or Kelly Thomas.

In August 2010, Greenville, South Carolina, officers tasered and killed 39-year-old schizophrenic Andrew Torres while committing him to a mental facility. The coroner determined Torres’ enlarged heart might have been stopped by the jolt. Tasers can induce arrhythmia, fibrillation and cardiac arrest, especially in people with heart conditions.

http://youtu.be/3SyEsotPgpg

On July 5, 2012, downtown Fullerton, California, onlookers expressed horror at the brutal murder of a 37-year-old mentally ill “gentle homeless man.” Photographs of his pulverized face raise the question: Did repeated police tasering or beating kill Kelly Thomas?

San Francisco’s taser history

Both Mesha Irizarry and MaryKate Connor, executive director of the now de-funded Caduceus Outreach Services, report that the problem of psychiatrically ill San Franciscans being killed by SFPD during crisis situations was first addressed in 1995-96 by concerned advocates and providers.

Connor wrote that in 1997, plans were first presented to the San Francisco Police Commission for officers in teams to receive extensive – 40 hours – specialized training “to be available to respond to any ‘800 calls’ (police dispatch code for responding to a disturbed person), to authorize them to take the lead in psychiatric crisis situations, and to have these officers volunteer for this specialized position to ensure they have the interest and empathy needed for this specialized role.”

Irizarry is adamant: “Non-lethal weapons are not a ‘new idea.’ They were defeated three times in the past.” In 2004, 2008 and 2011, following public outcry after police shootings of San Franciscans, the SFPD had again promoted “less lethal” tasers.

Each time citizen groups rejected lethal and non-lethal weapons, pushing instead for the “Memphis model,” which relies on verbally de-escalating people in crisis. New SFPD chiefs sent officers, mental health professionals and advocates to Memphis to “study” verbal de-escalation techniques.

Now, in October-November 2012, SFPD Chief Greg Suhr and the Police Commission are holding six community forums, three on the non-lethality of tasers and three on use of force.

SFPD will cover two topics:

- Why SFPD again wants tasers.

- “Potential Implementation Plan” language describing how officers would use tasers once allowed to procure them.

The public will comment.

Why Crisis Intervention Teams work

Warns MaryKate Connor, mistakes are made when uniformed police, bearing weapons with state authority to kill you, escalate the situation. Police shouting orders at people in crisis that scare more than comfort them escalates terror reactions that block commands.

Connor believes people with psychiatric disabilities are generally not valued nor liked. Nowhere is that more evident than in the police response to them. “What happens to people who are in public crisis who are perceived to be ‘crazy’ is criminal. They get killed for needing help,” she said.

Mental Health Association Associate Director Michael Gause concurs. The focus of the MHA is around reducing the stigma – the bias and prejudice people with mental health conditions face.

A mental health professional can use verbal de-escalation and not get stabbed because he is not:

- Wearing a uniform,

- Carrying a weapon, or

- In a power struggle with the person in crisis.

The difference between the police and mental health response is the professional approach, Connor explains:

- Mental health workers’ approach is to discover who the sufferer is and why they are so upset.

- Police are trained to see something out of the ordinary as suspicious and potentially criminal, requiring “control of the subject.” As a paramilitary organization, police are conditioned to one approach – command of someone losing his mind “out of control” in public.

- As with mental health workers, Connor notes, officers choosing to be on a specialized Crisis Intervention Team may be motivated by special life experience with mental illness. Such officers won’t view people in crises as just an “EDP” (Emotionally Disturbed Person), “an 800 call,” or someone “BB” behaving bizarrely. As in the way the mental health worker views the sufferer, the officer will see the individual as a whole person.

Observes Connor, the biggest difference between the Memphis police and elsewhere is that not only are they a special status team with sensitization training, but

- Team members are volunteers, motivated not by slightly more pay, but by concern for people in crisis.

- “Brass from the chief down authorize and support it.”

- “Authority is given to the officers to make this work.”

In February of 2011, when George Gascon was chief, he brought Lt. Sam Cochran and Andy Devine from Memphis. They gave presentations to the SFPD and the Police Commission. Gascon said: “Not only do I want special officers trained. We need to have everybody trained in this technique.” They sent people to Memphis – among them MHA’s Gause.

During the time the original police crisis intervention program was developed and funded, there were three police chiefs in San Francisco. No one carries this on to the next police administration, observes Connor in frustration. The same issues and crises repeatedly surface. People continue being shot.

How do you make this cultural shift? Says Connor, “Tactically speaking, if Memphis and San Francisco create the same good solutions – not a giant sticky net or a mass tranquillizer gun – with the authorization and authority to make a shift in attitude and culture that allows behavioral change, the Crisis Intervention Team model could work.”

Michael Gause asserts that the Mental Health Association supports CIT principles, verbal de-escalation techniques. “We also support police intention to reduce risk to individuals with mental health conditions,” he added.

CIT – Crisis Intervention Team training – is an internationally recognized best practice. “It works,” said Gause.

CIT trainings

Gause worked beside veterans’ advocates, case managers and psychiatric emergency experts in developing the CIT training course outline which is focused on crisis behaviors and covers a full spectrum of topics such as suicides, PTSD, and veterans’ issues.

He reported that Cmdr. Mikael Ali and several organizations, including the Mental Health Association, organized three CIT trainings.

The last four-day, 40-hour training was in June 2012. Another training is coming up Oct. 22-25.

For updates on the No Tasers campaign, join the No Taser email group, at http://groups.yahoo.com/group/NO_TASER. And please attend the police-community forums.

Six police community forums on ‘less lethal weapons’

Monday, Oct. 22, 6 p.m., Hamilton Center, 1900 Geary Blvd at Steiner: A Community Meeting on Less Than Lethal Weapons and Updated Taser Information. A subcommittee of the Commission, composed of Commissioners Angela Chan, Julius Turman and Judith Loftus, will meet with Chief Suhr and the public.

Tuesday, Oct. 23, 6 p.m., Scottish Rite Cultural Center, 2850 19th Ave. near Stern Grove: Use of Force Discussion

Tuesday, Oct. 30, 6 p.m., Downtown High School, 693 Vermont St., Potrero Hill: Use of Force Discussion

Wednesday, Oct. 17, 6 p.m., South of Market Recreation Center Auditorium, 270 Sixth St.: Special Session on Tasers. Note this Police Commission meeting will not be held at Room 400, City Hall; it is a neighborhood meeting in the Southern District. Public comment will be heard, and Southern Station Acting Capt. Steven Balma will make a presentation concerning Southern District public protection issues. Tasers may be subsumed under “public protections.”

Wednesdays, Oct. 24 and Nov. 7, 6 p.m., Room 400, City Hall: Use of Force Discussion

Carol Harvey is a San Francisco political journalist specializing in human rights and civil rights. She can be reached at carolharveysf@yahoo.com.