by Amy Buckley

In America there are 24 million children with an incarcerated parent. These children are affected in numerous ways and those effects can be detrimental, often attributing to rebellious behavior and other problems. Judges do not consider children when sentencing a parent, nor do they consider where those children will go or who will care for them. As parents, we must think about our children before we act because the courts have no money and our children are the ones suffering.

When a parent is incarcerated, it creates financial and material hardships, as well as causing an imbalance in family relationships and structure. For the children, a parent’s incarceration often results in behavior and performance problems in school and at home and can also cause social and institutional stigma and shame. These children are more susceptible to depression and anger, and many have symptoms of post-traumatic stress reaction.

Children are forced to give up the things that matter the most to them: their homes, safety, public status, private self-image, and their primary source of comfort and affection. Most young children identify themselves with their parents or blame themselves for their parents’ absence. These children should not have to suffer.

As parents, it is important to do what we can to maintain a relationship with our children while we serve our sentences. This relationship will help improve the child’s emotional response to our incarceration and will encourage parent-child attachment. We must reiterate to our children that our incarceration is in no way their fault and help to rebuild their self-esteem by encouragement and positive reinforcement.

Keeping the lines of communication open and being willing to listen to our children is also very important. Children need to know that even though we are absent from the home, we are still available to help solve problems and offer advice.

Children are forced to give up the things that matter the most to them: their homes, safety, public status, private self-image, and their primary source of comfort and affection.

Just as parents feel the need to protect their children, children often feel the need to protect their parents. I have experienced this personally in my relationship with my sons. I feel that it is important to let our children know that they can tell or ask us anything without the fear of us becoming angry.

If a child senses that they have angered or upset their parent, they often change the subject of the conversation or withdraw completely from the conversation and their parent. How we control ourselves when communicating with our children will determine the child’s willingness to open up to us.

Children are very perceptive, and the things they hear about their parents and themselves affects them as much as their parents’ incarceration. They can become defensive and angry, acting out and coming to resent the people around them. This can result in behavioral problems which can be self-destructive if not quickly worked through and corrected.

Some children may need counseling to help them adjust to and understand the things that are happening in their lives, while others may be able to cope without professional help. We must make sure that our children have mental and emotional stability during what is a capricious time in their lives.

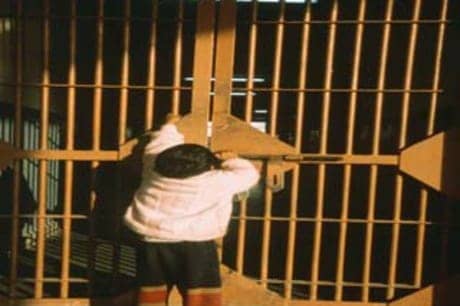

Another way to help our children is through personal visits. Unfortunately, more than half of incarcerated parents have never had a personal visit from their children, the Sentencing Project reported in 2009. The distance between the parents’ last place of residence and the prison where they are now housed is one factor that makes it difficult for family members to bring children to see their parents.

Other factors include, but are not limited to, financial instability and lack of transportation. Personal visits are important to both parents and children, improving the children’s emotional life and helping reduce the likelihood of recidivism.

Our children have needs, and those needs should be considered when sentences are handed down. Laws must be implemented to expand the judge’s capacity to consider children. Family impact statements should be included in pre-sentence investigation reports, and all information in that report should be taken into consideration. Judges should assess the effects a given sentence will have on children and their families and then choose the least detrimental sentence or sentencing alternative, i.e., probation, house arrest, drug rehabilitation etc.

More than half of incarcerated parents have never had a personal visit from their children.

An incarcerated person with strong family bonds will be more likely to succeed upon release. For children, a strong, well maintained relationship with the absent parent is key to their successful development. The parent-child relationship should always be recognized and valued even during adverse circumstances. When our children are treated with respect, have their potential recognized and are afforded opportunities, they have a better chance of overcoming the stigma of their parents’ incarceration.

We as parents have made choices that have forever affected our children. The damage that has been caused is often indelible, but with the proper care and love the effects can be lessened. Our children can grow into healthy adults despite our incarceration.

We need to encourage our children and reassure them that they are loved. When our children see us striving to do better, they will be more apt to do the same. Our mistakes should not ruin our children’s prospects for the rest of their lives. Our children are our future and they should not have to worry about being judged for our mistakes.

An incarcerated person with strong family bonds will be more likely to succeed upon release. For children, a strong, well maintained relationship with the absent parent is key to their successful development.

As an incarcerated mother, I see how my sons have been affected by my absence. They are teenagers now, young men really, and I have worked hard to maintain a relationship with them. I see the justice system as a failure! It has failed not only the children, but the incarcerated as well. Many changes need to be made and our children need their rights protected. We cannot give up. Our children are too important, so we must continue to fight for them.

In closing, I would like to leave you with some statistics to ponder: Three in 100 American children will go to sleep tonight with a parent in jail or prison; one in eight African American children has a parent behind bars; one in 10 children of prisoners will be incarcerated before reaching the age of 18, according to the UN Human Rights Council.

These statistics should be an eye-opener for us. We must not forget our children and, for them, we must dare to struggle, dare to win!

Send our sister some love and light: Amy Buckley, 150005, KNRCF, 374 Stennis Ind. Park Rd., DeKalb, MS 39328.