by Shaka At-thinnen

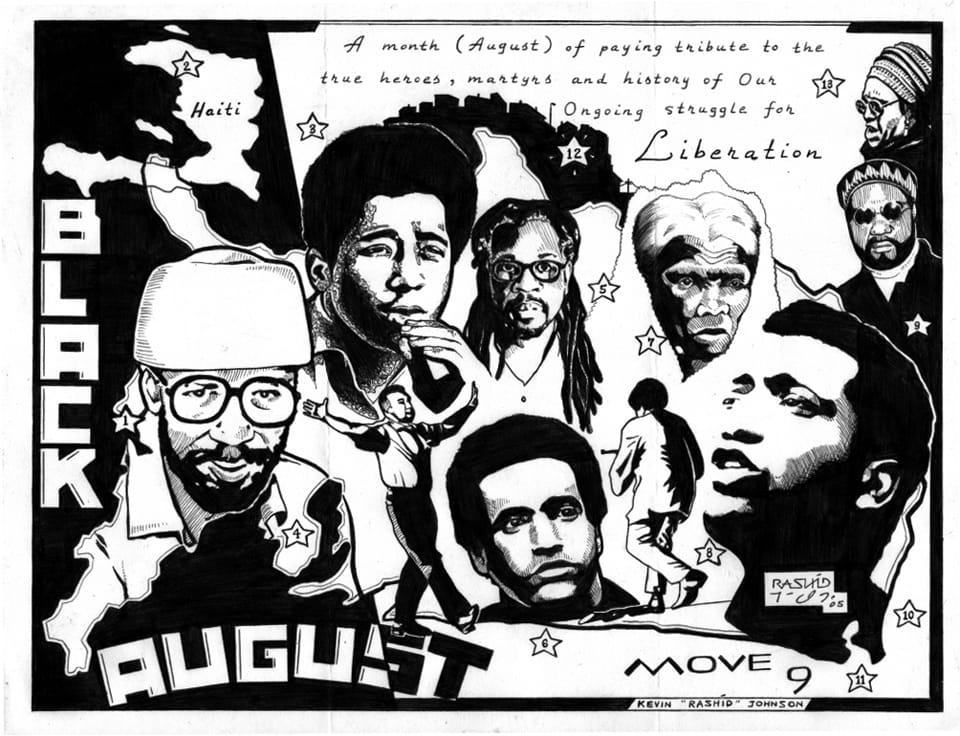

When the concept of Black August manifested in 1979, many thought it was simply a focus group protest growing out of the avoidable death of Khatari Gaulden on Aug. 1, 1978, in the San Quentin prison infirmary. Survival for Africans in California’s prison population of 20,000 inmates had to that point been recognized by some as a bit more than problematic.

More than a few noteworthy individuals stood firm against the oppressive actions and policies of a totally arbitrary and unchecked prison environment operating outside the influence and even the awareness of most people in society. The ‘60s and ‘70s saw many of those individuals executed in one set-up or another that got rid of what the state termed “so-called revolutionaries.”

This was in essence the Black Prison Movement. There was nothing remotely romantic about the time or how we survived what those known and unknown did not, and some few of us still have the scars to prove it.

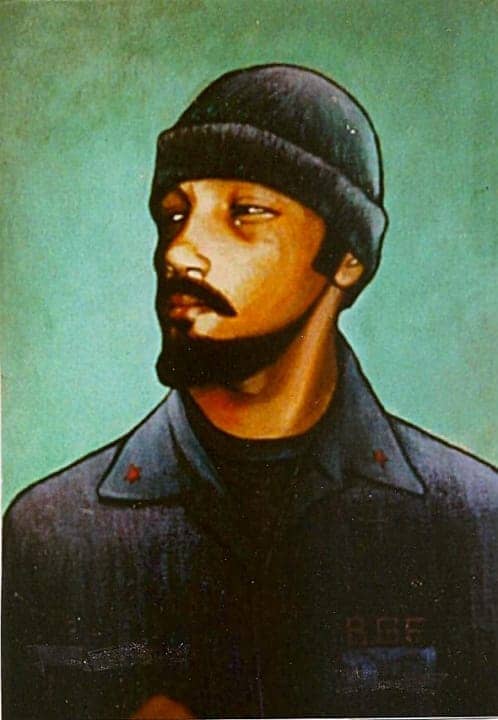

We rallied to the call of one who saw clearly the nature of the beast and the unceremonious lifelong commitment it would take to simply keep the hounds at bay, not win the war. After Comrade and the Man-Child were taken from us, many retired to other pursuits. Some fell into hedonistic trances that exist to this day, while others frankly lost the will to fight on for any reason.

For those of us left standing firm, the prevailing onslaught felt as though oppression was our peculiar domain. The state decided to concentrate a special portion for the bear we called wonderful one. This one became the symbol of the state’s concentrated hate for surviving that particularly gruesome day that took the life of their most consistent target, Comrade.

In 1971, the state prison system began implementing policies and practices designed to establish and maintain a death grip on the prison population. New programs were created to categorize all inmates into departments for specific handling.

Into this already provocative setting some of California’s most predatory racists were added to insure constant strife and separation. Africans were now under both physical and mental attack 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Prison guards and sometimes a friend or two from the streets would dress up in their hooded KKK outfits and conduct a midnight klan interrogation on someone from their blacklist. This was always done after hours of general movement and so was not common knowledge to most inmates.

These beatings were quite as thorough as those handed out in daylight hours but with that added directly racist intent. The food and water were as often as not drugged or fouled in some way that led to long periods of starvation and unified protest.

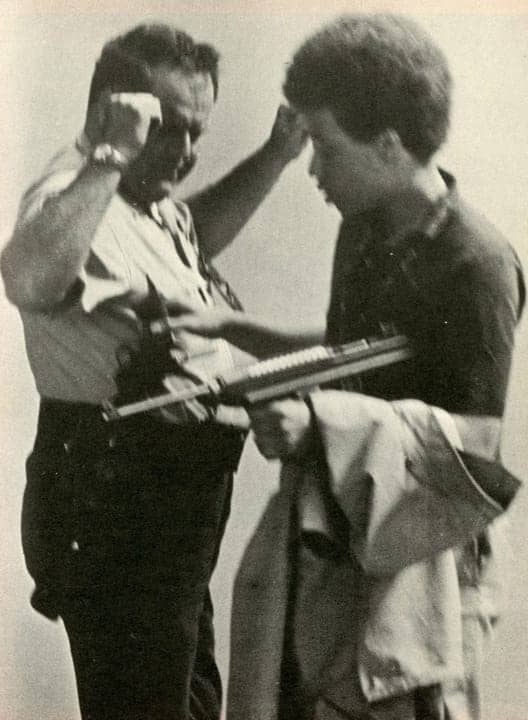

Once again those in power devised horrific methods of maintaining the façade of control. Individual inmates were singled out for demonstrations of absolute authority by gassing and beating them senseless with the flat side of axe handles so as not to break bones unintentionally.

One sustained puff from the moon gun and you were immediately convulsed on the floor vomiting, urinating, defecating and crying like a baby while all of your muscles danced as if they had a mind of their own. The moon gun devastated the intended target and unfortunately all of the cells on that side of the unit and tickled a few throats around the corner of the cell block. The intended victim was dragged off and reminded where he was over and over again until he was considered apologetic and then hidden in the infirmary for a few days.

Selected individuals from those who remained enduring the slowly vanishing odor and effects of the gas were moved into the stark isolation cells in the lower depths of the cell block. These cells consisted of a solid concrete block for a bed and depending on how much of an example they wanted to make out of you, there was sometimes a ragged blanket.

There was a sink and a six inch hole in the center of the floor that was your toilet. Stepping into that hole in the absolute darkness was not a pleasant experience and sometimes resulted in serious injury. They of course controlled the working of both the sink and wide open toilet from outside. You could go for days without the toilet being flushed and by now we all know what those fumes will do to your health in a confined space.

The truly unfortunate captive was given one meal a day through a thick iron door that when closed left you in complete darkness with only the sounds of you and the creatures that scurried unseen around you. Your meal consisted of a glass of water and what some called jupe balls. They combined all of the meals of the day, including dessert, into a loaf and you were given a slice. Jupe balls supposedly met the daily nutrition requirement for California prisoners.

This circumventing of the law went on for months at a time in many instances and was not confined to what went on in lock-up. San Quentin prison in particular practiced the evil policy of welding certain individuals they felt needed a good breaking in their cells on the first tier for a year and a day.

Understanding the absolute absence of culture led to an even more determined effort at rebirth. Some few still clung to remnants of the aptly termed grave from which we had mentally and physically crawled to stand firm as that new man Comrade spoke of.

Knowing that in great part the life styles that poisoned the communities we left beyond the walls were in reality prison life, change within ourselves was the first task. We established a new culture of behavior and growth that bound us to those lessons Comrade tried to instill before his death.

Our culture was now one of survival, protection for those Africans under constant assault by racists and other individuals and gangs, political and cultural awareness classes and most importantly personal growth. No more negroes!

The example of this did not go unnoticed by those in power because conscious, aware Africans don’t bend easily and resist the lash and temptation of the prevailing prison winds. Our captors financed armies of snitches, sellouts, uncle toms and other miscreants with shorter sentences, prison transfers, positions of privilege, conjugal visits with prostitutes and of course good old fashioned money.

These people, some of whom still maintain positions of influence both inside prison and out to this day, were incredibly damaging to the culture we fought and died to build: a working example of what should and could be in how we related to one another, our immediate environment and the world. We of course hoped that some of us would one day return to our communities as better men now fully able and motivated to be positive role models and progressive influences.

We continued to die and suffer the oppressively tightening grip of those who would see us exterminated like a bad cold. We continued to reach out to a public that seemed further away with each incidence of abuse we were forced to endure.

Journalists and many others reporting on conditions inside quite often relied on their imaginations in the absence of first hand information. Another problem was letting the outside world know critical details as close to their being useful as possible. Court cases died quick deaths for lack of validation because inmates were beaten into submission, hidden by transfer from one prison to another or the ever optional mysterious or accidental death.

We continued to exist in another reality that ignored all attempts to see rehabilitation in its finest hour by anyone not a part of what pained us. The culture we had established and come to embrace as our way of life protected us from the mundane prison existence and aided our growth as men and new Africans. Anywhere they moved us in the system, there were folks of like mind, especially in the holes and segregation units.

The Black Prison Movement was all of this and more for nearly two decades by the time Aug. 1, 1978, dawned. We had lost so many, not only in August, but every calendar month of the year.

We fought and died not only for a subjugated African captive, but also for those Africans flooding the prisons as victims of the war against the liberation movements on the streets. We embraced them as kindred spirits and made sure no harm came to them.

Most were atmosphere people simply caught up in the rush, but some few exemplified revolutionary action and stood out from the rest. As they passed through, it seems now that some of them took very little note of how they continued to exist alive and move on to other locales as icons of the struggle for liberation.

It is no mystery why our tormentors held true to their objective of totally erasing us from every aspect of prison life both mentally and physically. One by one, two by two, three by three, the sellouts, toms and snitches put our names in the basket for removal from the general population.

So many people were beaten and dragged away in chains they had to designate whole buildings lock-up units with brand new classification. Through it all we tried to reach out to any and all parties concerned with the CDC’s growing indifference to court rulings and basic human rights and dignity.

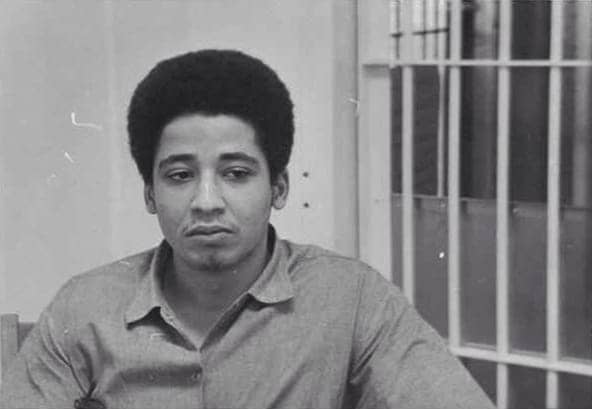

It was Khatari who maintained in leadership the steadfast principles, goals and convictions of Comrade George. In taking on this mantle he became another of the California Department of Correction’s most hated targets ever. They tried set-ups by paying a not surprising number of inmates on different occasions to kill him. They concocted bogus court cases through the willing participation of that same captive source of fellow convicts who, once bribed, lied while singing like canaries. None of their schemes worked no matter the number of attempts or passage of years.

On Aug. 1, 1978, Khatari was playing football with a few other brothers on the Adjustment Center secure yard below death row. He tripped and fell hitting his head on a pipe sticking out of the brick wall and was taken to the prison infirmary with a severe head injury. The prison saw immediately that they could not help him on site, but the administration refused to allow him to be taken to a public hospital.

The reasoning they used as an explanation was security. San Quentin prison claimed they could not put together enough security to transport a gravely ill and totally helpless patient, so they watched while he lay there in the prison infirmary for hours until they finally took him to Ross Hospital in Marin for a brain scan. After several more hours passed, he was taken to San Francisco General; but after so many hours of inattention, he was beyond hope.

To say we were devastated is nowhere near what was felt by those who loved and respected him. We turned our grief and anger into positive motion and set about working on making sure the world outside understood why he died.

The most critical problem with existing in a vacuum is getting information out of it intact. Our vacuum consisted of years in which we were dealt every cruelty imaginable while those brothers standing firm beside us perished along the way.

To maintain the integrity of those years, to acknowledge the significance of those we lost and why, to move it all forward in a manner that focused on awareness and a faster, more universal response – those are the true reasons why our cultural Black Prison Movement began, endured and continued to function no matter the adversity.

Our torment was a Blackness that lived, breathed death and agony while systematically crushing all hope of reprieve. Black was our prison journey, this Black Prison Movement that spawned so much and inspired so many, Black was our future and who we were in that moment.

August as a month of the calendar year held little significance, but in that month lives of untold significance and potential were cruelly and maliciously torn from us. August was now the designation and symbol of both our painful loss and determined rebirth.

Black August epitomized African captives standing firm acknowledging a calamitous journey and moving forward unbroken. We created the Black August Organizing Committee to show the outside world the best of what we had through extreme adversity learned and the new men we had become.

We sang the praises of our fallen leaders, teachers and brothers and sisters by the examples we set working in the community. We worked to build healthy communities by planting fresh produce gardens in back yards through the East Bay while educating the people to the nature of prison life for Africans.

We championed issues that directly touched the communities, all the while maintaining the connection of inside and out. We spread the word and the true name of our tormentor behind the walls.

The California Department of Corrections and their minions are subsidiaries of the national behemoth, the Prison Industrial Complex. This is how and why Black August was conceived and created and why it continues to this day. Black August Resistance!

Shaka At-thinnin is chairman of the Black August Organizing Committee – national headquarters Oakland, California. He can be reached at royboomba@aol.com.