by Denis O’Hearn, author of ‘Nothing but an Unfinished Song: Bobby Sands, the Irish Hunger Striker Who Ignited a Generation’

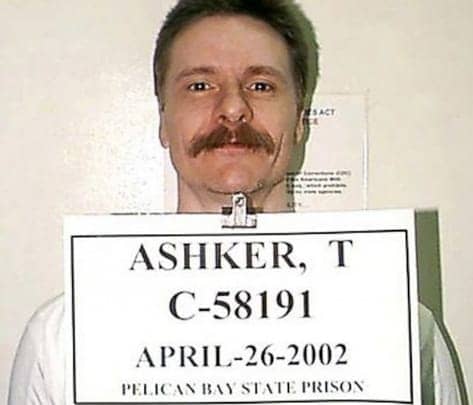

Todd Ashker is on hunger strike in Pelican Bay. California authorities call him “gang leader” and “terrorist.” I want to say something few people want to hear.

Todd Ashker is my friend.

What puzzles and amazes me is how Todd remains such a remarkable man while living in conditions most of the world considers to be torture.

Sit in a closet for an hour. Put a metal screen over the doorway that you can barely see through. Now think about sitting there for 25 years, communicating only with strangers in nearby closets by shouting out the door.

Oh, by the way, your arm has been shattered by a bullet fired at close range by a guard and you are in constant pain. Federal courts have repeatedly ordered CDCR to provide additional medical treatment, but CDCR has done nothing. You have been told that you could get the treatment if you offer or invent information on others you may not even know. But if you did, they, too, would be thrown into a closet.

This is Todd Ashker’s life.

I met Todd when he participated in my university course. Along with us, he and nine other prisoners in long-term isolation across the United States read books by prison “experts.” Then the students wrote to the prisoners and asked how their experiences compared with what the sociologists and criminologists had written.

A few prisoners stood out. Todd Ashker was top of the list. We have corresponded ever since. I visited him in Pelican Bay recently, his first personal visit since 2007.

What puzzles and amazes me is how Todd remains such a remarkable man while living in conditions most of the world considers to be torture.

What I found in Todd is an astute observer who places the welfare of his fellows over his own wellbeing. Or, I should say, he sees his own wellbeing completely tied to that of his fellows. I once asked him, “How did you decide that solidarity with others was more important than improving your own conditions of life?”

He responded that he would not put other people in danger just so he could get out of SHU or gain parole. Doing so would be “a selfish and despicable act.”

Among other things, they read about Bobby Sands and Irish prisoners who endured British prison policies that in many ways resembled Pelican Bay today. After years of protest, these Irishmen finally used the only peaceful weapon they had left. Ten men died on hunger strike in 1981.

I’ve known Irish hunger strikers, as I have known hunger strikers in Turkish prisons and in the United States. For them, hunger striking is no selfish or individual act. It is an act of deepest solidarity and friendship. Knowing Todd Ashker, I am not surprised that he is at the forefront of such an act of selflessness. Nor am I surprised that he always insisted that their protest must be peaceful.

California is not alone. Until recently, a handful of prisoners in Ohio State Penitentiary were also kept in strict isolation for nearly 20 years. In January 2011 they went on hunger strike with simple demands: to embrace their family on visits, to recreate together (Black and white together, it mattered not to them).

They began to discuss how they could help each other regain some of the dignity that was taken away by California’s inhumane policy of long-term isolation.

As in California, the authorities said at first that they would never give in. Then wiser heads prevailed. After less than two weeks, the demands were granted and the hunger strike ended.

Today, OSP is a calmer, more humane place.

On my way from my last visit with Todd, I met the wife of another prisoner on Pelican Bay’s “short corridor.”

“I visit my husband every weekend, but I have not touched him for 22 years,” she told me.

For her sake. For Todd Ashker. So that prisoners and guards and all of us can regain some humanity, let wiser heads prevail in California, as in Ohio.

Denis O’Hearn is author of “Nothing but an Unfinished Song: Bobby Sands, the Irish Hunger Striker Who Ignited a Generation” (Nation Books, 2006). He is professor of sociology at Binghamton University – SUNY, visiting professor at Boğaziçi University Istanbul, and has been Keough visiting professor, Keough-Naughton Institute for Irish Studies, at Notre Dame University. He can be reached via his friend, Professor Andrej Grubacic, at agrubacic@ciis.edu.