by Clarence B. Jones, co-written with Stuart Connelly

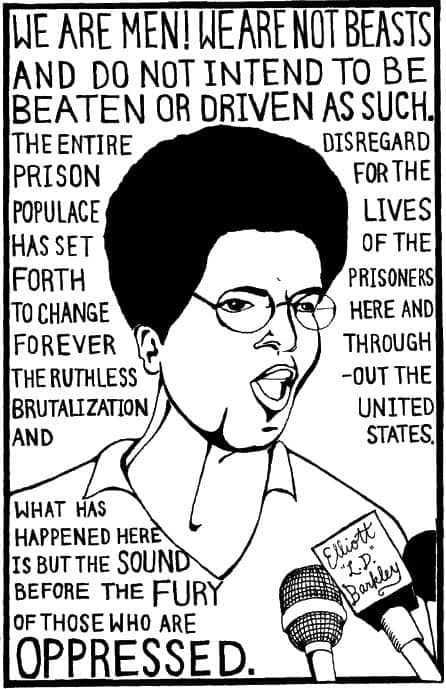

Sept. 9, 2013, marks the 42th anniversary of the prison uprising at the Attica Correctional Facility in upstate New York. Forty-two men, mostly inmates, were killed in the armed retaking of the prison under the orders of Gov. Nelson Rockefeller.

Men – and, by extension, governments – always make poor decisions under pressure. The story of the Attica Prison uprising is the story of pressure squeezing out the worst decision of all: the decision to take lives.

First a group of men yielded to this pressure. Then their government did.

The uprising at Attica took place early on in the angry decade of the 1970s. This anger clearly and naturally flowed out from the end of the ‘60s, the direct result of a cocktail of disappointment – part the simmering savagery of Vietnam, part the violent opposition to the Civil Rights Movement.

Yes, real progress took place on the racial front, but it was nevertheless a battlefield. There may have been the “Summer of Love” in that decade, but both Kennedy brothers were slain, four little girls were blown up at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Malcolm X was gunned down in Harlem, they shot Viola Liuzzio in a moving car in Selma, Alabama, and they lynched civil rights workers Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman in Philadelphia, Mississippi. My beloved friend Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tenn., on April 4, 1968. The country was nearly set afire in the rioting aftermath.

I’ve been reflecting back over the years since Attica and questioning what lessons, if any, we had learned as a nation from that experience. I began to think about the prison uprising within the context of America’s struggle with violence and our traditional response of incarceration for convicted perpetrators of acts of violence against law-abiding citizens within our society. I remembered the sociological axiom that violence lies like molten lava beneath the surface of society, just waiting to erupt.

I discussed my Attica experiences with my friend and colleague Stuart Connelly – writer, journalist, and co-author with me of the 2011 book, “Behind the Dream: The Making of the Speech That Transformed a Nation.” As a result of our conversations, we decided to write a retrospective commentary on my experiences 40 years ago. “Uprising: Understanding Attica, Revolution, and the Incarceration State” is that commentary. The way we treat prisoners – then as well as now – demands Civil Rights Movement-level attention.

It certainly must have been the norm in many if not most other penitentiaries, but in Attica, prisoners were treated almost like animals. In that sense, the prison was a microcosm of the penal world in general. In the list of grievances that came to light during the uprising, we learned much about what we, as a society, were doing in the prison system, with our tax money and in our name, that we would find repellent.

The incarcerated in Attica were given only a single roll of toilet paper a month, for example. Only allowed to take one shower per week. Not only were Muslims denied their constitutional right to hold religious services, but pork – explicitly forbidden by the Quran – was often the only protein served in the mess. Newspapers were kept out of the prison library. Magazines that had any information about prison reform or prisoners’ rights were censored.

On the first day, the inmates requested my presence there along with 10 other “observers.” At the time I was a 40-year-old newspaper publisher. This sort of hostage-crisis monitoring was not my training, but these observers were asked to give voice to the inmates’ grievances and help negotiate a peaceful settlement.

If you know anything at all about the uprising at Attica, it is likely this: There was no peaceful resolution. I found no real chance for peace there. What I left Attica with, instead of success, was compelling insight into the desperation that can bring people to acts of madness, self-destruction and amoral judgment. And what I’ve seen in the intervening years reminds me that Attica was only the beginning, the “tipping point.”

The story of the Attica uprising has never before been told from the twin perspective, with the eyewitness vantage point of one inside – yet not incarcerated – braided with the contemporary social dissection of America’s “state of mind” regarding its treatment of convicted criminals. It is a view that’s instructional about the politics of power we deal with every day. There are lessons learned from my personal experience behind Attica’s soaring, scarred walls that can and should be applied to today’s incarceration philosophy.

Not many Americans are acquainted with the Attica uprising on any level of detail, as they may be with other battles for civil rights. It is perhaps best known to most through a pop culture filter, from the scene in Sidney Lumet’s “Dog Day Afternoon,” supposedly an ad-libbed line by Al Pacino, as his trapped-at-the-scene-of-the-crime bank robber character tries to get the bystanders on his side by pushing to get the famous “At-ti-ca! At-ti-ca!” chant to catch on.

“I’m mad as hell, and I’m not going to take it anymore!”

On its 40th anniversary, the rebellion at Attica is not merely a harrowing memory of desperate decisions, the struggle for control, the animal panic of cornered men, but a harbinger of things to come. In retrospect, the drifting cloud of teargas that ended the siege and started the bloodshed was a kind of smoke signal, pointing the way to dangerous trends in our very concept of justice: an incarceration society that punishes rather than rehabilitates and a new form of segregation.

Clarence B. Jones is Scholar in Residence at the Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University. This story first appeared in the Huffington Post on Sept. 9, 2011; the first sentence has been updated.

Attica Is All Of Us from Freedom Archives on Vimeo.