by Galen Kusic

If you haven’t heard about the “twin tunnels” yet, get ready to hear a lot.

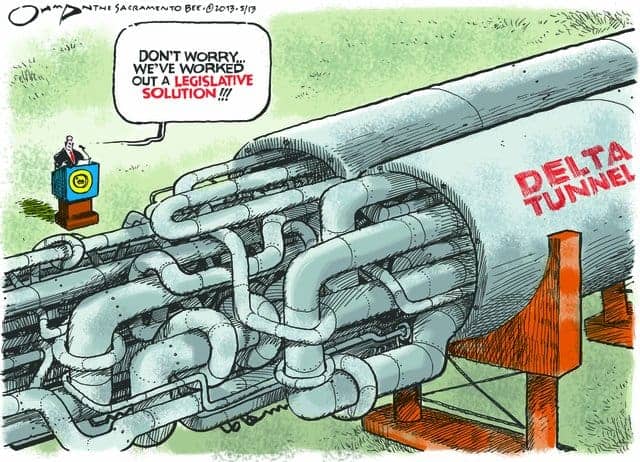

By now, most California residents have heard about Gov. Jerry Brown’s plan to construct two 40-foot diameter peripheral tunnels 150-feet below the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, the state’s largest and most critical water supply. The plan has been estimated to cost between $25 and $67 billion, depending on whom you ask – opponents or proponents.

The plan itself, known as the Bay Delta Conservation Plan (BDCP), has been under intense scrutiny from local and congressional lawmakers, Delta residents, farmers and fishermen.

While Gov. Brown touts his plan as adhering to the 2009 Delta Reform Act’s charge of “co-equal goals” to provide a more reliable water supply to California, while improving the Delta’s current failing ecosystem – environmentalists, scientists and water activists are not buying it.

Opponents of the plan say those same “co-equal goals” also call for “reducing reliance on the Delta.” But, according to opponents, building three massive intakes and two huge conveyance tunnels – large enough to fit a bus through – does not reduce Bay-Delta dependence, but increases it.

When the Delta’s land was reclaimed in the late 1800s to provide land for farming and the railroad system, it was not clear that the tidal marsh ecosystem that once was would nearly be wiped out in modern times.

Yet, for over 70 years, the Delta thrived as a commercial fishery and one of the epicenters for the world’s best agricultural production.

That all changed when former Gov. Edmond Brown pushed through the State Water Project in the late ‘50s, a man-made system that pumps water from Tracy in the south Delta into the California Aqueduct, supplying farms and urban centers as far south as San Diego. The transport of water from the northern part of the state to southern California has increased over the years with added demand from new housing developments, oil fracking and, most frequently, permanent crops for large agribusinesses on the west side of the San Joaquin Valley.

What came with the increased water exporting was decimation of the Delta’s fisheries, nearly wiping out salmon to extinction – while leaving Delta smelt endangered. The pumping from the Tracy pumps has disturbed natural river flows and drawn fish into dead end sloughs or to be killed at the pumps themselves.

As a result, these Sacramento River Delta communities’ economies will be severely impacted. Pumping at the Tracy pumps will continue 50 percent of the time – while allocating even more water from the system than ever before.

“BDCP’s own analysis shows that in drought years like this one, it will not provide one more new drop of water,” said Jonas Minton of the California Planning and Conservation League in January. “Spend it when we’ve got it, and forget the dry times are inevitable.”

The largest estuary on the West Coast of the Americas, the Delta serves as home to numerous endangered species, fish and migratory birds that rely on the fertile region to survive year after year. BDCP’s Environmental Impact Report (EIR/EIS) was released in December, a 40,000 page document. Within that document, 52 severe and unavoidable impacts are listed to the Delta ecosystem, economy and communities within the Primary Zone of the statutory Delta.

Yet the plan is described as a conservation plan, calling for restoration of over 140,000 acres to tidal wetland habitat – destroying thousands of acres of prime farmland in the process.

“The EIR/EIS contains 750 impacts,” said North Delta Water Agency Manager Melinda Terry. “That’s a lot of impacts, which means a lot of mitigation. There are 218 impacts to aquatic species out of that 750; 52 of those are unavoidable, which means they won’t be mitigated. That includes agriculture.”

Terry explained that during the 10-year construction period, even lands not directly impacted will be forced to cease production of farming due to change in soils and water tables.

“All of the Delta is on ground water, not county water,” she said. “That means they will have to de-water, and homes and businesses could not have water for six to nine years.”

Terry explained that the cost of these mitigations is really unknown and that other impacts would include the abandonment of homes and businesses during the construction period. This is the only Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP) which literally provides no benefits in the location where the project is occurring.

Instead, the benefits are transferred to an entirely separate region, far from ground zero.

Flood protection is a vital issue that has not been incorporated into the BDCP. When a Delta levee breached in 1986, the state was on the hook for a $400 million lawsuit with over 3,000 litigants that ultimately prevailed, because the system was changed without the proper flood protection.

“The BDCP proposes to make the largest modifications to the state flood system since it was built,” said Terry. “There is one major flood out of every decade. They do not talk about flood flows – they are not analyzed at all.”

More of those impacts include pile driving, every day for a year. Trucks will be moving “tunnel muck,” excavated to build the tunnels, 24 hours a day, seven days a week – causing an increase in greenhouse gas emissions.

The Greater Sandhill Crane migrates through the Pacific Flyway to Staten Island each year before heading south to Mexico. The tunnels’ alignment is set directly below the crane preserve – possibly destroying vital acres of farmland habitat for these majestic birds, who return to within feet of the same nesting place each year.

“Cranes will find the habitat they need,” said Deputy Director of Delta and Statewide Water Management Paul Helliker at a BDCP public meeting. We are going for no net loss of habitat. You see cranes all over the Delta. I don’t know that they’re that picky. If they see habitat, they will go to it.”

Water quality in all areas of the Delta will be greatly impaired, forcing cities like Antioch to upgrade water treatment plants for drinking water. Solano County cities will be forced to build a $550 million North Bay aqueduct to supply the county with sufficient water.

The plan, viewed as the largest public works project in California history, has yet to secure financing, though no independent cost-benefit analysis has been conducted.

The state water contractors, the main proponents behind the plan, have in theory agreed to pay for the construction of the tunnels, but the public would be on the hook for the habitat restoration.

These mega-water agencies include Metropolitan Water District of Los Angeles, Kern County Water Agency and Westlands Water District, the nation’s largest water agency. Westlands, while being the largest agency, only supplies water to a small group of mega-growers on the westside of the San Joaquin Valley, a virtual desert.

There, permanent crops are being planted at a record pace to meet the demand of overseas markets for nuts and citrus. These permanent crops take a high amount of water year-round, as opponents to the plan cite that planting crops where water is scarce is simply bad business.

Metropolitan and Westlands combined took 55 percent of the Delta’s exported water last year.

“Regardless of where you pump, you can’t take more water out of the system. This project will rely on the taxpayers to continue and pay higher taxes,” said Ralph Furlong of Bakersfield at a BDCP public meeting in January.

Yet, the farmers in the south feel it is their right to take water from the north. The problem is that there is only so much water to take and, without sufficient water storage throughout the state, during dry years there simply isn’t enough water to go around.

Several alternative proposals have been brought forth to deter BDCP, but the Brown administration has managed to install a plan that will not require a vote from the public for approval. Instead, state and federal lead environmental agencies will be responsible for permitting the plan for construction. The public comment period is quickly coming to a close on June 14.

“The drought has imposed real hardship on our state and sharpened focus on water management. Instead of reigniting a pointless water war over the distribution of this precious resource, it is time to work together for commonsense policies that add to our water supply,” said Congressman John Garamendi, D-Fairfield.

This was a reaction to the announcement of several drought bills that would curtail pumping restrictions and ignore the Endangered Species Act to pump more water south. Garamendi has produced his own “Water Plan for All California,” focusing on storage, groundwater, recycling and existing water rights, rather than exporting water south.

Delta legislators Garamendi, State Sen. Lois Wolk, D-Davis, and Assemblymember Jim Frazier, D-Oakley, have been leading the charge against the BDCP’s implementation. Wolk has authored an alternative water bond for the upcoming November election, and Frazier has introduced a bill that would require legislative review of the BDCP before it could be permitted.

At an Assembly hearing in February, the Legislative Analyst’s Office, a non-partisan entity, cited the BDCP’s potential for greater land costs, potential cost overruns, cost estimates that do not capture potential range of costs and an unclear future whether the tunnel’s benefits will outweigh the cost.

Activist groups like Restore the Delta, North Delta CARES, the Environmental Water Caucus and Friends of the River have waged a successful opposition, denouncing many of the Department of Water Resources claims within the BDCP by exposing facts – but the water wars rage on, as Delta communities unite to fight the plan.

“I think we’ve got a real fighting chance to put this thing (BDCP) to rest,” said Sacramento County Supervisor Don Nottoli. “It’s not a sprint; it’s a marathon. We can’t sacrifice one part of the state for another. It will leave a legacy of ill will.”

Galen Kusic, editor of the River News-Herald & Isleton Journal, can be reached at glin83@yahoo.com.