by Mike Parker

Richmond Mayor Tom Butt has set himself up to be the spokesman for landlords in a campaign against rent control in Richmond. The jump in Richmond rents the past few years, reflecting trends in the Bay Area, has produced new calls for the progressive city council to respond with rent control and “just cause” requirements for eviction.

Mayor Butt has written several articles in his widely read E-Forum attempting to debunk the ideas behind rent control. He reprints articles that repeat the doctrinaire free market supply and demand theory as though the housing markets of today were not rigged and distorted by banks and wealthy speculators. Additionally, the mayor’s arguments are classic examples of misusing numbers and logic.

- Averages

Tom’s first written attack came in response to a tenant protest over rents being raised by 20 percent. Tom’s defense of an increase from $1,000 to $1,200 a month is a classic case of manipulating data to support an argument.

Tom argues that the new rate is reasonable because it is still below the average rent in Richmond. It is a misleading comparison. Average includes the wealthier neighborhoods in Richmond – Pt. Richmond, Hilltop, El Sobrante, North and East. These are mixed in with much lower rents in neighborhoods like the Iron Triangle, resulting in an “average” value that is not relevant for any specific neighborhood.

A more appropriate figure – and one which realtors use – would be to compare rents for “comparable” apartments in the area. And even this measure doesn’t tell us it’s a fair rent but that demographic pressures – i.e. people moving into Richmond – might have forced up all rents.

Tom does not provide us with an appropriate comparison. Interestingly, at the city-hosted meeting on the housing element on April 9, a landlord who has apartments in several areas of Richmond and was at the meeting to argue against rent control, stated that the going rate in the same Iron Triangle area was about $1,000 per month.

- Comparisons of area averages

Tom keeps presenting tables to show that current Richmond rental rates are significantly lower than elsewhere in the Bay Area. Somehow he thinks this proves that we don’t need rent control in Richmond. On the contrary, the graphs and tables he uses support moving quickly on rent control. Since rents are higher and climbing quickly in other communities in the area, it means that there will be increasing movement to the Richmond area.

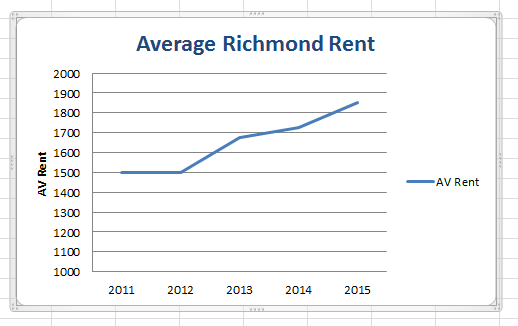

The graph below shows rents in Richmond rising far faster than inflation. In the last few years, we have seen working people pushed out of San Francisco as rents and housing values become among the highest in the country. Unless we want Richmond residents to be priced out of their homes and Richmond to become a homogenous community of only those who can afford high rents, we have to move now to protect our residents – not after the rents become unaffordably high.

Tom’s argument is like saying that we don’t have to worry about an outbreak of flu in San Francisco until we have the same sickness rate here. When you have advanced notice of something bad coming, wise people use the time to prepare.

- False causation

Tom keeps repeating the argument that rent control doesn’t work because San Francisco, Berkeley and Oakland, all of which adopted rent control and just cause ordinances decades ago, have not been successful in slowing spiking rental rates that soar far above those of Richmond (E-Forum 4/13).

This argument is like the argument that hospitals don’t help people because everybody in them is sick. It is sickness that causes hospitals to be built. It was the rising rents in Berkeley, San Francisco and Oakland that forced them to adopt rent control. As a result of state laws written to protect landlords at the expense of renters, the coverage is unfortunately limited, but at least rent control has kept the rents in older buildings more affordable than in the rest of those cities.

- Minimizing who would be helped

Tom’s latest argument is designed to show that under rent control only “a relatively few tenants could benefit initially but over time will dwindle.” He then goes on to correctly show that because of the pro-landlord state legislation “only … 3,158 [Richmond] units would be subject to rent control.”

Tom tries to reduce this number further by pointing out that when these units are vacant, state law allows the landlord to raise the rent to the current market value. While rents in these units would go up, at least new tenants who moved in to them would be protected by rent control and would be assured that the landlord could not unreasonably increase the rent as long as they remained in the unit.

But, if rent control will apply to a relatively small number of units, as Tom argues, what is his problem? We can estimate that these 3,000 plus units probably house over 10,000 people, who are disproportionately the working poor. Why would we not protect those whom we can? Why lead a campaign that denies protection for these individuals and families?

Yes, unfortunately state law prohibits us from helping more of our residents. How about helping to change the state law?

- Market economics and windfall profits

Classic free market economics says the market, if left alone, should reach an equilibrium, where the market price will reflect both what people can pay and the cost to produce the product or service. In the case of housing, cost includes a payment for the work of the landlord and a “reasonable” return (profit) on the landlord’s investment.

So what happens when demand picks up? In the case of housing, the landlord’s cost stays the same, but the amount she or he can and will charge goes up. The landlord makes more profit. The greater profits are supposedly the incentive for developers to build more housing to get the higher profits, and as the housing supply increases, the price goes back down until only normal profits are made.

Economists call the higher profits made during the period before the market returns to equilibrium “windfall profits.” Windfall profits are not “earned.” They may well be the result of luck or the result of speculation.

Richmond rents had been fairly stable for years and were not reduced during the economic crash of 2008. They started rising rapidly in 2011 and have risen about 26 percent in the last four-year period. The rents rose far faster than costs.

The general inflation rate was a bit over 6 percent and the Urban Consumer Price Index for the Bay Area rose 10 percent in the same four-year period. This difference between the rising costs and the much higher rising rental prices is windfall profits.

There are many reasons that the supply of rental housing is not built quickly enough to fill demand and bring rental rates down to a more reasonable rate – these include a lack of space as well as a lag time between development of the need and construction of new rental stock. In addition, as the demographics of the Bay Area change with increasing wealth, developers find luxury housing far more profitable and there is less available investment for affordable housing. In other words, the growth and demographic shift in the Bay Area create huge demands and keep windfall profits very high.

Tom argues that rent control means that “new renters often pay the highest possible rent as landlords struggle to make up losses.” The reality is that most landlords charge the highest possible rent they think they can get anyway, because they can and do charge the maximum they can get people to pay. Rent control at least limits the ability to increase the rent yet more unreasonably, after the renter has moved in.

Rent control also includes a way to insure that fair landlords are able to cover costs and get a fair return on their labor and investment.

- Rent control and development?

Does rent control slow down development?

The state law, known as Costa-Hawkins, that exempts housing built after 1995 guarantees that rent control does not apply to new rental units. A glance at San Francisco, Oakland and Berkeley should be proof that rent control does not stop development.

- Stable and diverse neighborhoods through rent control

The main reason to support rent control is that in the Bay Area the housing market is producing windfall profits for some while driving renters out. Our community thrives on stability and diversity, not constant churning. Stability means you get to know your neighbors, can work with them to make the neighborhoods safe and work together to improve the neighborhood. Diversity means a richness of backgrounds and experiences and valuing of all our residents.

We want homeowners and renters to take ownership of the community, not see themselves as transients or forced to be transients. That means we have to help protect both homeowners and renters against rapacious banks, speculators and a government which only bails out the rich.

Tom says there are few winners and many losers with rent control. Stable communities mean most of us win. And all of us who care about economic justice and diversity win. When renters can spend more of their money on immediate needs, the money circulates in the local economy. And who loses? A few landlords. Where is the evidence that rent control stops development and discourages business? In San Francisco or Berkeley or Oakland?

- Problems with rent control

We will need to work together to create an effective rent control program designed to protect lower income residents. We will need to find ways to prevent the development of a “shadow market” to finance implementation and smooth running of the program and to take measures to make sure that fair and inexpensive procedures are available to both renters and small landlords.

We will have to figure out how to make sure that landlords do not allow controlled units to fall into disrepair. We will have to figure out the best response to the California-given right to landlords who want to convert to condos under the Ellis Act to get around rent control.

Yes, rent control also may provide some difficulty for some good landlords. But we need to keep in mind how difficult it will be for thousands – who already pay too much of their income for rent – to cope with runaway rent increases.

Rent control does not come close to solving the whole problem. Other policies are needed. We need to raise the income of poor families through training and jobs programs so that they can afford to live in higher cost housing.

Tom is right that we need programs to build more affordable housing. It will likely take a federal program to build enough. But while we work to get these programs underway, rent control can help relieve some of the economic pressure and help a significant number of people.

Mike Parker is co-coordinator of the Richmond Progressive Alliance and can be reached at mparker@rts-tech.com. The RPA has a long history of supporting rent control, though it has not yet taken a position on specifics of a rent control proposal. Follow this debate by signing up to receive the Richmond Progressive Alliance Newsletter at http://www.richmondprogressivealliance.net. This story previously appeared in the RPA newsletter and in Beyond Chron.