The prison industrial complex turned me into a valuable commodity.

by Flores Forbes, Columbia University Associate Vice President for Policy and Program Implementation

“Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” – 13th Amendment, U.S. Constitution, proposed on Jan. 31, 1865, and ratified on Dec. 6, 1865

I am often asked if the use of the words “slave narrative” in the title of my book, “Invisible Men: A Contemporary Slave Narrative in the Era of Mass Incarceration,” is a trope or metaphor. It’s not. Though few Americans know it, the exception clause in the 13th Amendment makes a person a slave when they are convicted of a crime and sent to prison.

I know that former President Barack Obama, a constitutional scholar and a Black man, understands this. I applaud his efforts to address issues of mass incarceration. I understand the symbolism of his visit to a federal prison, the only American president to ever do so. These were important first steps, but there is a long road ahead.

While I was incarcerated in California in the 1980s, I was a slave in San Quentin’s furniture factory, where I was paid 15 cents an hour. The office chairs I made were sold to the various state entities, among them the University of California, for $300 to $400.

Though few Americans know it, the exception clause in the 13th Amendment makes a person a slave when they are convicted of a crime and sent to prison.

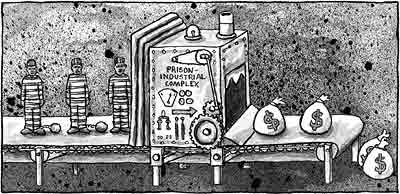

That is what I call slave labor. According to Jaron Browne’s article, entitled “Rooted in Slavery: Prison Labor Exploitation,” “there are currently over 70 factories in California’s 33 prisons, alone.” What I witnessed as a slave for the California Department of Corrections Industries was a contemporary, self-sufficient slave labor operation that included farms, fisheries, ranches, clothing and shoe factories, all worked by inmate slaves being paid 15 cents an hour like I was. Each inmate paid less than $2 dollars a day generates $41,540.00. annually for the state of California.

My book deals with the at best difficult and often impossible challenge for former incarcerated people as they attempt so-called reentry and reintegration after having served their time and overpaid their debt to society as slaves. The title of the book is intended to draw attention to the gross inequities of penal servitude. The Prison Industrial Complex allocates on average $32,000 taxpayer dollars a year to incarcerate one inmate. When I was released I was given $200, a pat on the back, and a bus ticket if I needed one. What I and thousands of former slave laborers require is better preparation to reenter society after prison. What we now get is no better than being driven off southern plantations at the end of the Civil War, landless, penniless, and uneducated.

My book deals with the at best difficult and often impossible challenge for former incarcerated people as they attempt so-called reentry and reintegration after having served their time and overpaid their debt to society as slaves.

Going to prison in America is contemporary slavery, prison industries modern day plantations. I’ll celebrate when the words “slave narrative” are a trope or metaphor. Unfortunately, until we as a society commit our minds, hearts and resources to welcoming the formerly incarcerated as returning citizens, Invisible Men: A Contemporary Slave Narrative in the Era of Mass Incarceration, will remain the story of millions.

Flores Forbes, associate vice president for policy and program implementation at Columbia University in New York, is an urban planner and writer who lives in Harlem. His first book, “Will You Die With Me? My Life and the Black Panther Party,” published by Skyhorse Publishers in the fall of 2016, discusses his 10 years in the Black Panther Party, three years as a fugitive and five years in prison. His most recent book, “Invisible Men: A Contemporary Slave Narrative in the Era of Mass Incarceration,” follows his life after prison and his journey to becoming a successful urban planner while overcoming the stigma of being formerly incarcerated and how he and many Black men must hide in plain sight until they can remove that stigma. He can be reached at Faf2106@columbia.edu. This story first appeared on Huffington Post.