by Nevin Long

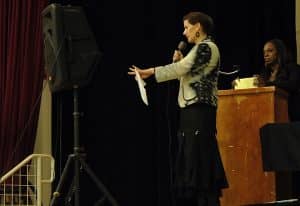

Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf faced heated questions and comments from attendees at a community forum on homelessness held at Allen Temple Baptist Church on Sept. 22.

The discussion went from cordial to contentious when the subject of homeless encampment removal was raised. Many residents of the Deep East Oakland neighborhood were angered by perceived inertia on the part of city and county officials regarding the creation of adequate shelter.

Several commenters cited the lack of capacity at temporary shelters, including those managed by local non-profits and the city itself, a problem which Schaaf acknowledged. She said that all local shelters, including the Henry Robinson House, had no availability.

A temporary solution to the problem, Schaaf said, was a proposal set for discussion at the next City Council meeting. There, councilors would debate creating three of what Schaaf called “outdoor navigation centers.” These centers would not be city sanctioned encampments, rather they would provide medical and hygiene services to unhoused Oakland residents.

“These three sites, we’re hoping, are going to provide a place for us to humanely and compassionately work with this population,” Schaaf said.

Still, community members were unsatisfied with officials’ lack of a tangible plan to create new housing, prompting Schaaf to lament budget restrictions. She said this was the reason Oakland had not created facilities like San Francisco’s Multi-Service Center. Schaaf said San Francisco had “10 times” the budget of Oakland.

Mattie Johnson, who co-directs a ministerial outreach program targeting Oakland’s sex workers, disputed Schaaf’s assertions. She says that the city has chosen to make other programs higher priorities than housing.

“Housing now,” Johnson said, “It is possible. It is not impossible.”

Budget data from the city of Oakland indicates that Measure KK, which was ratified by voters last year and intended to provide affordable housing, has roughly $27 million in funding. According to Open Budget: Oakland, the city discretionary fund for fiscal year 2016-2017 contained over $570 million.

Roughly 41 percent of that amount, $234 million, went to the police department, accounting for the single largest expenditure of the fund.

Panelist Kathleen Clanon, director of Alameda County Health Care Services Agency, supported Schaaf’s description of a need for centralized locations designed to provide services to the homeless. She said her agency had offered housing and other supportive services to members of encampments, but had had trouble tracking residents of the 84th Street encampment.

Police had recently dismantled the encampment. Since then, Clanon said, her agency had lost track of 27 of its 29 former residents.

“Some people just don’t like to be tracked,” Clanon said.

Neither Schaaf nor Clanon offered response to questions as to whether the HCSA may have had an easier time keeping track of encampment residents had the camp not been dismantled.

Dislocation of homeless encampments was a prime point of debate. Schaaf said only two encampments in the city had been permanently removed, citing health hazards as the cause.

Derrick Soo, a homeless resident of Oakland, disputed the number, saying Union Pacific Railroad demolished a camp just 30 days prior. Soo estimates that the encampment, known as The Village, was home to 50 residents, some of whom were families with children.

“That was crushed and destroyed by Union Pacific Railroad about 30 days ago,” said Soo.

Like many attendees of the town hall, Soo feels that far more is being done to evict homeless people than house them. He says that such demolitions are a daily occurrence in Oakland and says police dislocation of homeless encampments are all too regular.

“The sweeps are killing us,” he said.

Nevin Long, a San Francisco State University journalism student, is interning with the Bay View. He can be reached via nevin@sfbayview.com.