Dec. 10, 2017, was the 50th anniversary of Redding’s transition

by Norman (Otis) Richmond aka Jalali

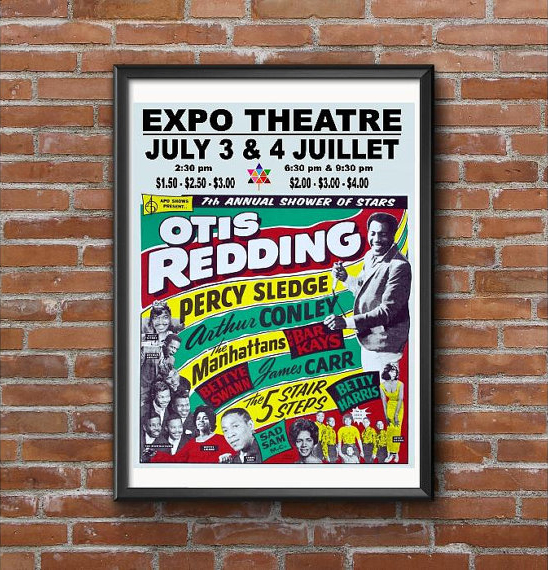

When I moved from the suburbs of Toronto to downtown, I got a new postman. He always talked about how he still had his tickets to see Otis Ray Redding Jr. (Sept. 9, 1941-Dec. 10, 1967) perform at the University of Toronto’s Varsity Stadium. Redding had been penciled in to sing in Toronto after his Dec. 10 date in Madison, Wisconsin. Redding, however, never made it to the land of Drake.

Many of today’s artists remember Redding’s contribution to the business of music. Jay Z and Kanye West introduced the hip-hop generation to Redding in 2011 when they recorded the track, “Otis.” The dynamic duo sampled the Big O’s rendition of “Try a Little Tenderness.”

According to Wikipedia, “Jay and West performed the song at all the stops on their 2011 Watch the Throne Tour. It was also performed at the 2011 MTV Video Music Awards and at the 2012 Radio 1’s Big Weekend musical festival. At the 54th Grammy Awards in 2012, ‘Otis’ was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Rap Song and won a Grammy for Best Rap Performance.”

Forty-four years before that, Redding was on top – known as the most popular male vocalist on Planet Earth. Redding was so popular in England that he ended Elvis Presley’s eight-year reign as the “world’s best male vocalist” on Melody Maker’s annual pop poll in 1967.

The life and times of Redding is the subject a new book, “Otis Redding: An Unfinished Life,” by Jonathan Gould. The volume has been receiving critical acclaim by the corporate and even the so-called alternative press. Rolling Stone magazine’s headline read: “Epic New Otis Redding Biography Sheds Light on the Singer’s Life and Times.”

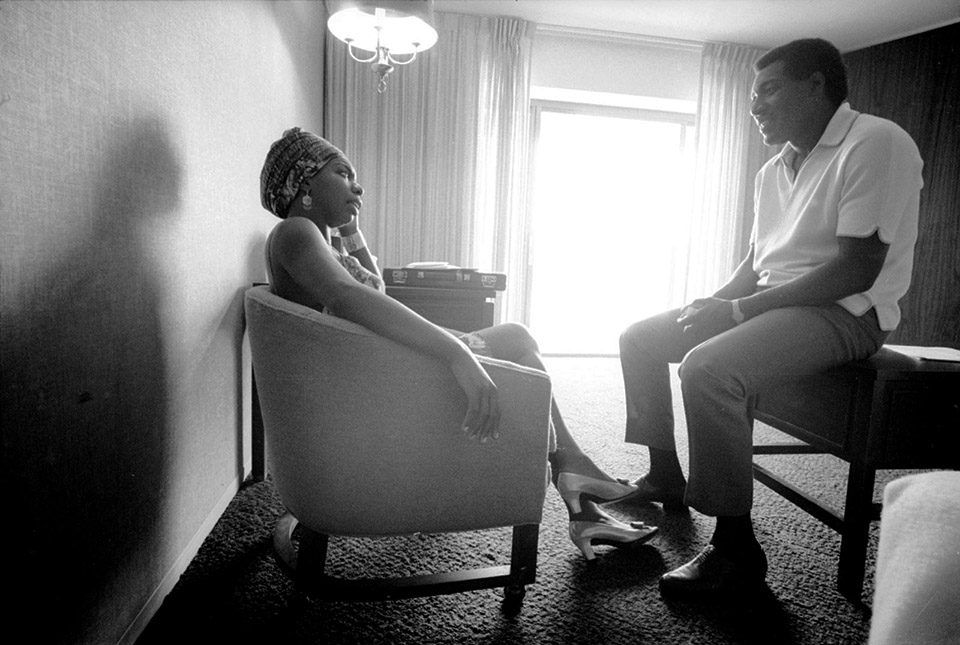

Gould stated in his new book that “no interview or article mentioning him (Otis Redding) ever appeared in Muhammad Speaks.” Darryl Cowherd refutes Gould. Says Cowherd: “Simply put, that’s a lie. Because I conducted an interview with Otis Redding that was published in Muhammad Speaks Sept. 23, 1966, and I have a copy of that published article to substantiate what I’m saying.”

Phil Warden, who served as Redding’s manager from 1959 until Redding’s death in 1967, spoke to Gould. Gould quotes Warden as saying, “He went through about a three month deal with a Black Muslim group that strained the relationship greatly … There was even an interview in a Black Muslim magazine that Otis was going to announce his intentions to become a Muslim.”

Thirty-six years ago, I wrote about this issue in Al Hamilton’s African weekly in Toronto, Contrast. I wrote, “The con lawyer Don Warden (today Dr. Khalid Al Mansour) pointed out on his San Francisco talk show at the time of Redding’s death that Redding was assassinated by the Mafia for daring to attempt to organize an independent, all Black music corporation with some of the major Black artists.”

Don Warden (today Dr. Khalid Al Mansour) pointed out on his San Francisco talk show at the time of Redding’s death that Redding was assassinated by the Mafia for daring to attempt to organize an independent, all Black music corporation with some of the major Black artists.

As far back as 1967, Amiri Baraka (formerly Leroi Jones) talked about Redding and his place in the African liberation movement. Baraka points out in his essay, “The Changing Same: R&B and the New Black Music” (1966), “Music is the consciousness, the expression of where we are. But then Otis Redding in interviews in Muhammad Speaks has said things … more ‘radical,’ Blacker, than many of the new musicians.”

The cultural giant Oscar Brown Jr. (October 10, 1926-May 29, 2005) was a singer, songwriter, playwright, poet, human rights activist and actor. Check his classic “Forty Acres and a Mule.” Brown pointed out to me that the state feared Africans in America controlling a Mickey Mouse Club. The controllers of the system see this as the poor attempting to seize the means of production.

Oscar Brown Jr. pointed out to me that the state feared Africans in America controlling a Mickey Mouse Club. The controllers of the system see this as the poor attempting to seize the means of production.

Redding was more than a singer; he was also a songwriter, record producer, arranger and talent scout. His style of singing gained inspiration from the gospel music that preceded the genre. Redding’s father, Otis Redding Sr., worked at Robins Air Force Base and preached on the weekends. Redding’s son Otis III followed him as a musician.

Arthur Conley was Redding’s protégé and his 1967 song “Sweet Soul Music” was written by Conley and Redding and is based on the Sam Cooke song “Yeah Man.” It reached the No. 2 spot on both the Billboard Hot 100 and the Billboard R&B chart.

J.W. Alexander, Sam Cooke’s business partner, sued both Redding and Conley for appropriating the melody. A settlement was reached in which Cooke’s name was added to the writer credits, and Otis Redding agreed to record some songs in the future from Kags Music, a Cooke-Alexander enterprise, according to Wikipedia.

Redding was at the height of his popularity when he joined the ancestors in 1968. In 1967, Redding won over the “Flower Power” crowd at the Monterey Pop Festival.

Historian Alice Echols followed the Big O’s career. Echols pointed out, “Redding had been wowing Black audiences for years. But few … in Monterey’s overwhelmingly white audience had ever seen him perform.”

He had such hits as “The Dock of the Bay,” “Try a Little Tenderness,” “These Arms of Mine,” “FA-FA-FA-FA-FA (Sad Song)” and “I Can’t Turn You Loose.” I can remember when Los Angeles Police Chief William H. Parker died on Saturday, July 16, 1966. When it was announced that Parker had passed, “I Can’t Turn You Loose” was on the radio. We turned the volume up and partied to the break of dawn.

Unlike today, when African artists dominate the pop charts, it wasn’t true in the pre-Black Power ‘60s. Echols continues, “For example, Redding’s absolutely perfect 1965 album, ‘Otis Blue: Otis Redding Sings Soul,’ was the best-selling R&B album in the country but only peaked as the 75th bestselling album overall.”

Karla Redding-Andrews, Otis’ daughter, told Consequence of Sound that by 1967 her father had begun building a relationship with white audiences by playing at fraternity parties at white colleges. But, “Europe was a whole other animal.

“They worshipped him over there! The Beatles sent a limo for him and the band when they arrived at the airport, and The Rolling Stones … still talk about Otis and what a huge influence he was on them.

“Monterey Pop opened him up to a whole new audience. These young hippie kids, not to mention all the industry folks and press who also attended the event, took him to a whole new level of star.”

With all due respect to Redding’s daughter Karla, she was only a child when her father passed. He was a “Star in the Ghetto” long before the Beatles sent the limo to the London airport.

Africans in North America, especially in so-called “chitlin’ circuit,” who supported him before he “crossed over,” were the first firm supporters of Redding. As I stated earlier, we turned the volume up and partied to the break of dawn and danced to the music of the Big O.

Norman (Otis) Richmond aka Jalali produces Diasporic Music, a radio show for https://blackpower96.org/, and writes the column Diasporic Music for the Burning Spear Newspaper monthly. He grew up in Los Angeles, leaving after refusing to fight in Vietnam because he felt that, like the Vietnamese, Africans in the United States were colonial subjects. Moving to Toronto, where he co-founded the Afro American Progressive Association and the Toronto Chapter of the Black Music Association, he won the Toronto Arts Award in 1992. Richmond began his career in journalism at the African Canadian weekly Contrast and went on to be published in the Toronto Star, Toronto Globe & Mail, National Post, the Jackson Advocate, Share, the Islander, the Black American, Pan African News Wire, Black Agenda Report, San Francisco Bay View and, internationally, the United Nations, the Jamaican Gleaner, the Nation (Barbados) and Pambazuka News. Learn more at https://normanotisrichmond.wordpress.com/ and email him at norman.o.richmond@gmail.com.

https://youtu.be/1Lf0kdI_QYQ