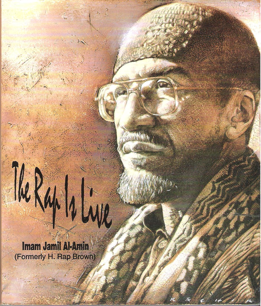

At the modern intersection of Islamophobia and the Black Lives Matter movement resides Jamil Al-Amin (formerly H. Rap Brown), the now forgotten civil rights activist and revolutionary leader who, 16 years ago this year, was sentenced to life imprisonment for the murder of Fulton County, Ga., Sheriff’s Deputy Ricky Leon Kinchen and the wounding of his partner, then-Sheriff’s Deputy Aldranon English, during a March 2000 gunfight.

At the modern intersection of Islamophobia and the Black Lives Matter movement resides Jamil Al-Amin (formerly H. Rap Brown), the now forgotten civil rights activist and revolutionary leader who, 16 years ago this year, was sentenced to life imprisonment for the murder of Fulton County, Ga., Sheriff’s Deputy Ricky Leon Kinchen and the wounding of his partner, then-Sheriff’s Deputy Aldranon English, during a March 2000 gunfight.

On the night of March 16, 2000, Deputies Kinchen and English were serving a warrant for the arrest of Al-Amin for missing a court hearing regarding a traffic stop when they were engaged in a gun battle outside Al-Amin’s grocery store in the West End neighborhood of Atlanta.

Kinchen died the next day in the hospital, and English, who had wounds that reminded arriving paramedic Kristin McGregor Jones of “Vietnam War wounds that I’ve seen in the movies,” later identified Al-Amin as the shooter before being rushed into surgery.

Prior to his murder trial, Al-Amin released a statement proclaiming his innocence and empathy for the family of Kinchen. Afterward, the trial judge, Stephanie B. Manis, placed a gag order on Al-Amin to prevent him from speaking.

That gag order has unofficially been reinstated over the past 10 years, ever since Al-Amin was secretly moved from a state prison in Georgia to the federal Administrative-Maximum (ADX) supermax prison in Florence, Colo., amounting to the de facto silencing of a man who has been targeted by the federal government for decades and who many believe is innocent of the crimes for which he’s been convicted.

Prior to his murder trial, Al-Amin released a statement proclaiming his innocence and empathy for the family of Kinchen. Afterward, the trial judge, Stephanie B. Manis, placed a gag order on Al-Amin to prevent him from speaking.

A perceived threat

Multiple writers, journalists, filmmakers and academics have attempted to reach out through the federal Bureau of Prisons to interview Al-Amin. All requests have been denied or ignored.

Early in 2017, professor and author Arun Kundnani, who is currently working on a biography of Al-Amin, “initiated the process [and] went through the paperwork,” but was told that an interview of Al-Amin “would not be allowed to take place,” Kundnani said.

“Every scholar and journalist has been denied over the past 10 years because of a ‘security risk,’” Kundnani said.

Multiple writers, journalists, filmmakers and academics have attempted to reach out through the federal Bureau of Prisons to interview Al-Amin. All requests have been denied or ignored.

The apparent “security risk” posed by Al-Amin stems from his time in the Georgia State Prison at Reidsville, where he was first imprisoned to serve his life sentence. Through the prison mail system, Al-Amin was asked to represent the needs of Muslim prisoners in the Georgia prison system. Yusha Abdul-Quddos, a prisoner at Reidsville at the time, asked Al-Amin to “facilitate and encourage communication between Muslim inmates and the Reidsville prison administration,” according to Al-Amin when he explained the intent of the communication to prison authorities.

Al-Amin accepted, later explaining to prison officials that he wanted to “help Muslim inmates achieve the same religious privileges afforded to inmates of other religions.” An intelligence unit within the prison inferred a greater threat and, after investigating the situation, released three reports that ultimately acknowledged that Al-Amin never “ordered other inmates at any prison to commit violence against prison officials” and was not tied, directly or indirectly, to any violence or unrest. Still, the unit requested that Al-Amin step down from his leadership role, and he acquiesced.

Two months later, though, on June 12, 2006, the FBI prepared a report based on the information gathered from the prison intelligence unit titled, “The Attempt to Radicalize the Georgia Department of Corrections’ Inmate Muslim Population.”

The purpose of the FBI report was to “provide insight into the motivation of a radical extremist exploiting an inmate population for personal gain and power.” Identifying Al-Amin as the “radical extremist,” the report continued, stating, “The solidarity movement could unify radical extremists, resulting in a power base within the inmate population which could promote organized recruitment drives for radical Islamist and collective disruptive or subversive behavior.”

The report claimed that the “assertion that one of the missions of the movement is to promote and defend the interests of incarcerated Muslims” was one of many “security and radicalization concerns.”

The prison shuffle

On July 30, 2007, a year after the FBI report, which lacked a single bit of evidence tying Al-Amin to extremism, Al-Amin was secretly transferred to the federal ADX prison without the knowledge of his family or legal counsel.

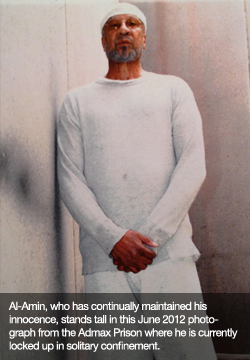

Al-Amin spent seven years in solitary confinement in the ADX, where he was locked in an underground cell for 23 hours a day. By early 2013, he’d developed a dental abscess that, by October 2013, had caused his jaw to swell. “He had fluid gushing out of his mouth [and began] swallowing the toxic fluids,” said Karima Al-Amin, Al-Amin’s wife and lawyer.

When she spoke with him in 2014, he sounded as if he was “out of breath, as if he was running; he had difficulty breathing,” Karima Al-Amin said. The toxic fluids “had gone into his lungs and chest area.”

On July 30, 2007, a year after the FBI report, which lacked a single bit of evidence tying Al-Amin to extremism, Al-Amin was secretly transferred to the federal ADX prison without the knowledge of his family or legal counsel.

While Al-Amin languished in the ADX with an increasingly serious medical condition, thousands of miles from his home in Atlanta, his family became worried. It was “rough for us, realizing he’s up in age now, thinking he’s in a cell and can’t get proper medical attention,” said Karima Al-Amin. The situation is “so emotionally draining. It finally hit Kairi [one of their sons] when he couldn’t sleep. Just thinking about his [father’s] health made [Kairi] break down.”

After his wife led a campaign to get her husband proper medical attention, Al-Amin was moved to the Butner Federal Medical Center, a federal prison in North Carolina, in July 2014.

Having formally been treated for the abscess, Al-Amin was then moved to the U.S. Penitentiary, Canaan, a federal prison in Pennsylvania. For the first time in his life sentence imprisonment, Al-Amin was placed in general population, out of solitary confinement. But by early 2016, he was moved again, this time to U.S. Penitentiary, Tucson, a federal prison in Arizona, where he is currently held, cut off from speaking to the outside world.

An open letter to the Federal Bureau of Prisons

Through “policy documents made available by the Georgia Department of Corrections, the BOP [Bureau of Prisons] … assessed that [Al-Amin] is a security risk – someone who is convicted of harming a law enforcement officer is a certain risk,” said Kundnani, who is seeking to interview Al-Amin in the Arizona prison. “But while at Reidsville, he was granted interviews,” Kundnani pointed out; therefore the “reason they give now – nature of conviction – would have applied earlier, not just over the past 10 years.”

“Serial killers are interviewed in prison, but he’s not allowed to communicate with the outside world in the form of an interview. It’s something that needs to be addressed,” Kundnani said.

As a result, Kundnani published an open letter in December 2017 aimed at the BOP and the state of Georgia, demanding an end to the isolation of Al-Amin and allowing academics and journalists access to him.

Kundnani hopes that the open letter can get enough support from the world of academia so that he can “go back to the BOP and ask them to review their decision in unjustly silencing [Al-Amin].”

“Serial killers are interviewed in prison, but he’s not allowed to communicate with the outside world in the form of an interview. It’s something that needs to be addressed,” Kundnani said.

“The suggestion that I’d be in danger by interviewing him, that’s ridiculous. Whose security is at risk?” Kundnani asked rhetorically. “So the reason must lie somewhere else.”

A decades-long target

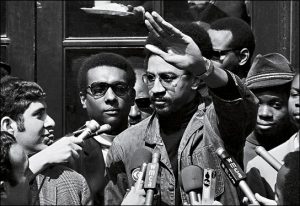

Federal authorities have long sought to discredit, silence and punish Al-Amin. As part of the FBI’s illegal Counterintelligence Program, or COINTELPRO, J. Edgar Hoover sent a memorandum dated Aug. 25, 1967, to all FBI offices regarding “Black Nationalist Hate Groups” (eerily similar to the supposed current “black identity extremist“ threat identified by the FBI).

The memo ordered all FBI offices to “expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize” all individuals and organizations considered a threat. Al-Amin, then H. Rap Brown, listed among three others – Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture), Elijah Muhammad and Maxwell Stanford (Muhammad Ahmed) – was to be given “particular emphasis.”

Federal authorities have long sought to discredit, silence and punish Al-Amin.

The surveillance continued throughout the 1990s, as the FBI placed informants in Al‐Amin’s Atlanta community to try to connect him with criminal activity. Despite developing a 44,000‐page file on Al‐Amin, the FBI was unable to pin a single charge on him.

That all changed in May of 1999, when Al-Amin was pulled over by Cobb County, Ga., Police Officer Johnny Mack for driving a vehicle with a “drive-out tag,” which legally allowed new car owners to drive a vehicle for 30 days without officially registering it.

In a court hearing, Mack explained that stopping cars with drive-out tags was part of his “basic patrol,” even when there was no evidence of wrongdoing.

In light of new documents that were released by the FBI in 2013 per a long-standing Freedom of Information Act request initiated by Al-Amin’s wife, Karima, the traffic stop appears more targeted than random. On April 14, 1999, six weeks before Mack pulled over Al-Amin on May 31, an FBI document logging surveillance on Al-Amin stated he was “observed unloading unidentified items from a dark green Ford Explorer with dealer tags.”

According to Mack’s testimony, he ran a check on the vehicle identification number and the car was listed as stolen. At that point, Al‐Amin was removed from his vehicle and searched.

During the pat-down, Mack found a bill of sale for the vehicle and a police badge in Al‐Amin’s wallet. The bill of sale showed Al‐Amin as the rightful owner of the vehicle and that the honorary badge had been issued to Al‐Amin from the former mayor of White Hall, Ala., John Jackson.

Al‐Amin never presented the badge, and following the arrest, the mayor of White Hall sent a letter to officials in Georgia verifying the authenticity of the honorary badge. Still, Al‐Amin was charged with driving a stolen car, driving with expired insurance and impersonating a police officer.

After missing the court date for the traffic hearing, which Al-Amin asserts he was never told of after it had been rescheduled following a severe ice storm that hit Atlanta, Deputies Kinchen and English went to serve the warrant for his arrest that led to the gunfight.

Disputed evidence

Al-Amin’s trial lasted two months. Multiple elements of the prosecution’s narrative didn’t fit the physical evidence of the crime scene. The surviving deputy, English, swore that his attacker had gray eyes and that he and Kinchen had shot him. There were multiple 911 calls made after the shooting that identified a man “bleeding on the corner begging for a ride.”

But Al-Amin has brown eyes and, when captured four days after the gunfight, had no signs of any shooting-related injuries.

A witness testified that upon hearing shots fired, he looked out his window and saw a man of “average height, average build” firing a gun and was “absolutely positive” it wasn’t Al-Amin, who has a distinctively lean, 6-foot-5-inch frame.

Moreover, the guns found in Alabama during the arrest of Al-Amin did not have any fingerprints on them; nor did Al-Amin have any residue from shooting the guns on his hands or clothes. The latter was an important detail: Federal officers claimed that Al-Amin shot at them during his capture, and they even filed a federal indictment against him. The charges were dismissed in 2002 after multiple witnesses testified that federal officers were the only ones firing their weapons.

In addition, the prosecution provided no motive. No explanation was given as to why a well-respected religious leader of a burgeoning Atlanta community, on the night of one of the holiest days in the Muslim calendar – Eid al-Adha – would shoot at two black deputies serving him a warrant for missing a traffic-stop hearing.

Despite the lack of motive and actual evidence, the jury of nine blacks, two whites and one Hispanic returned a guilty verdict after five hours of deliberation. The jury decided against the death penalty and instead committed Al‐Amin to life in prison. The same day that his conviction was delivered, the state trial court ruled that the original traffic stop that started the whole ordeal had violated Al‐Amin’s Fourth Amendment right of protection from unreasonable search and seizure, and therefore had been illegal.

Since then, Al-Amin has been secretly moved from a state prison in Georgia to federal custody, where, at USP Tucson, he is currently imprisoned and still actively working with his lawyers to petition for a retrial.

The same day that his conviction was delivered, the state trial court ruled that the original traffic stop that started the whole ordeal had violated Al‐Amin’s Fourth Amendment right of protection from unreasonable search and seizure, and therefore had been illegal.

The appeal

The appeal for a retrial is being led by the law firm Kilpatrick Townsend & Stockton. KT&S originally was assigned Al‐Amin’s case pro bono when he brought a suit against the warden of the Georgia State Prison, Hugh Smith, and other prison officials for illegally opening mail from his legal counsel in violation of Georgia Department of Corrections’ procedures and Al-Amin’s constitutional rights.

As he researched the case, Allen Garrett and lead counsel and senior partner at KT&S A. Stephens Clay discovered retaliatory actions on the part of prison officials against Al‐Amin. Moreover, they came across the work of G. Terry Jackson and Linda Sheffield, Al‐Amin’s attorneys from his state appeal case in 2007.

The 2007 state appeal featured a deposition of Otis Jackson, a man who, on three separate occasions, confessed to the crime for which Al-Amin is imprisoned. Jackson’s deposition provided accurate details of the night of the shooting, from the type of weapons and ammunition used to the position of the deputies and vehicles during the shootout.

Jackson also matches the physical description of the eyewitness who saw the shooter – Jackson is listed as 5 feet 8 inches tall and 170 pounds, and he has gray eyes, matching the testimony given by Deputy English of the man who shot him.

The 2007 state appeal featured a deposition of Otis Jackson, a man who, on three separate occasions, confessed to the crime for which Al-Amin is imprisoned.

Jackson’s confession also matches the 911 calls reporting a bleeding man making his way through the neighborhood: In his confession he describes knocking on doors and trying to hitch a ride while bleeding from his wounds.

Jackson even has scars on his body from wounds he says were caused by the guns of the deputies during the gunfight. (Jackson, also known as James Santos, is currently serving a prison sentence at U.S. Penitentiary, McCreary, in Kentucky, for unrelated crimes. He is scheduled to be released in 2027.)

On March 7, Al-Amin’s current lawyers submitted an appeal petitioning for a new trial with the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Georgia, partly based on ignored evidence contradicting the prosecution’s claims, like the multiple confessions of Otis Jackson that were never presented to the jury and blatant violations of Al-Amin’s constitutional rights during the original trial.

During the prosecution’s closing arguments, a mock cross-examination was performed of Al-Amin – a gross violation of his Fifth Amendment right not to testify or to have his choice used against him, as the prosecution did.

Planting guns

Al-Amin’s defense was also refused the chance to cross-examine FBI agent Ron Campbell, a violation of the confrontation clause within the Sixth Amendment. Not only did Campbell admit to angrily spitting on and kicking Al-Amin after he was handcuffed, but his story concerning where he was during the hunt for Al-Amin prior to his capture was also inconsistent.

At one point, while looking through the wooded area where Al-Amin eventually was arrested, Campbell claimed that he was helped over a fence by other officers. Later, Campbell claimed that he was alone when he climbed the fence.

The details of Campbell’s story are important, specifically in relation to the finding of the guns at the scene and when he was alone. Although federal officers claimed that Al-Amin fired weapons at them prior to his arrest – a claim that was later dropped after multiple witnesses contradicted the charge – the guns found at the scene had neither fingerprints, DNA nor blood tying them to Al-Amin.

Al-Amin’s lawyers believe that Campbell planted the guns at the scene, referencing an incident five years earlier in 1995, when Campbell killed Glenn Thomas, a 23-year-old Black man in Philadelphia.

On June 1, 1995, Campbell and three Philadelphia police officers approached Thomas while he was sitting on a railing with two friends drinking a milkshake. Thomas was wanted for skipping bail and missing a court hearing for charges stemming from an assault on Housing Authority officers six months earlier.

Thomas started to run, but before he could get far, he was shot and killed by Campbell. The FBI and the Philadelphia officers claimed that Thomas pulled a gun and turned toward them to fire. However, witnesses to the shooting said Thomas didn’t have a gun.

Further contradicting Campbell’s claim was the fact that Thomas was shot in the back of the head and the gun found next to him had no fingerprints on it, leading many to believe the gun was planted on Thomas by Campbell.

Al-Amin’s defense wanted to question Campbell about his history of being accused of planting weapons on suspects, but the judge denied the attempt because Campbell, though investigated by the FBI’s Internal Affairs unit and subjected to a private criminal complaint calling for his arrest in the Superior Court of Pennsylvania, was never found guilty.

Now, 16 years after his conviction and 10 years since any journalist or academic has been able to interview him, Al-Amin sits in a federal prison, waiting for his case to make its way through the court of appeals. All the while, his family and supporters believe he’s innocent and simply another targeted victim of a decades-old federal vendetta.

‘We don’t want you talking’

The de facto silencing of Al-Amin is “more about what [he] represents, not the nature of his conviction. The government believes he’s a radical voice among Muslims and Black people, and they’d rather that his followers did not hear from him,” said Kundnani.

Khalil Abdul-Rahman, a close friend of Al-Amin’s and a leader of a Muslim community in Greensboro, N.C., recalled seeing Al-Amin in 2013 as a legal assistant to former U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clark, who visited Al-Amin at the ADX supermax prison in Colorado.

Al-Amin was “allowed out in the yard for a little bit with a few other prisoners … the [Hispanic prisoners] gravitated toward him, and when [they] were called back in, they asked the guards for Qurans,” Abdul-Rahman said. “[The then-] warden [David Berkebile] was watching the whole time,” and he turned to Al-Amin and said, “‘This is why we don’t want you talking.’”

Obaid H. Siddiqui, a writer and freelance journalist based in Philadelphia, can be reached at @OhSiddiqui. This story first appeared on The Root.