by Paco Taylor

While doing seemingly unrelated research on the web some years ago, I got an unexpected clue from an old Russian painting that we don’t know even half as much about St. Nicholas (aka Santa Claus) in America as we think we do. And after some 200 years of Christmastime tradition, you’d think that we’d know all that there is to know about a guy who has unrestricted access to our chimneys!

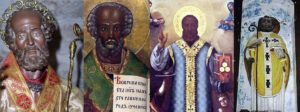

Never in a million cups of spiked eggnog would I have guessed that, in the much older holiday customs of the Dutch, St. Nicholas has, instead of elves, an African sidekick – who’s Muslim to boot! And you could’ve knocked me over with a snowflake when I learned how in the old icons of Italy, Russia, Spain and elsewhere, even the patron saint of Christmas himself is pictured as a grandfatherly-looking Black man.

Oh, by gosh, by golly. This’ll be a big, fat shock to Megyn Kelly, the TV personality who lost her job in October for her stunning defense of blackface. In 2013, while discussing a Slate article in which a blogger suggested a 21st century makeover for Santa, Kelly famously asked: “How do you just revise this in the middle of the legacy … and change Santa from White to Black?”

The answer to that is really much simpler than it would seem: You just start by issuing a long overdue retraction for getting your alternative facts wrong, because old St. Nick wasn’t actually white to begin with.

Here comes Sinterklass

Today, people around the world are familiar with the popularized depiction of Santa Claus: a chubby old gnome with a snow-colored beard, eight tiny reindeer, and an army of freckle-faced elves who leap at his beck and call.

In light of the multi-million-dollar impact that the legend of Santa has on the cult of retail, Santa has become a commercial icon in America, more powerful than The Avengers, Shuri, She-Ra, Black Panther, My Little Pony, Optimus Prime and rest of the Transformers combined.

And though commonly thought of as an American folk legend, Santa Claus owes most of his existence to old religious customs that came to this country with immigrants from Europe. Interwoven in our holiday tradition are the traditions of Spain, Germany, Italy and, above all, the Dutch Netherlands, where one of the clearest connections to the Santa tradition can be found.

Before becoming known in America as Santa Claus, this magical gift bearer was commonly referred to as “Sinter Claes” or “Sinterklass,” a Dutch language corruption of both the name and the religious title of Saint Nicholas, a fourth century bishop of the Eastern Orthodox Church.

And as Dutch tradition tells it, Sinterklass doesn’t travel by sled or live at the North Pole. He also doesn’t dress up in a red velvet suit trimmed with faux polar bear fur, or manage a year-round sweatshop staffed by toy-making elves.

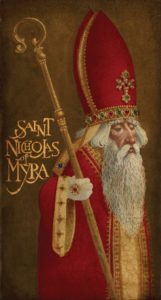

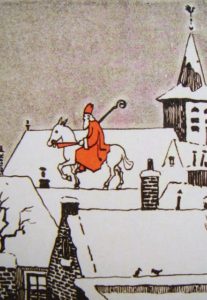

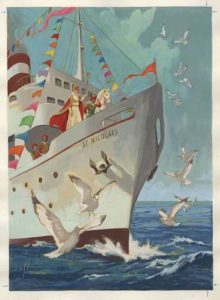

According to the Dutch, Sinterklass leaves his home in Spain (that’s right, Spain) around mid-November, traveling by steamship to the Netherlands to deliver gifts on Dec. 5, the eve of St. Nicholas’ Feast Day. Garbed in a red Episcopal robe with the pointed miter of a bishop on his head and a gold shepherd’s crook in hand, Sinterklaas’ role as a high priest of the Christian Church is on full display.

After reaching his destination, Sinterklass rides from house to house, and rooftop to rooftop, on the back of a white horse. Acting with impartial authority, down the chimney of each home he drops gifts for kids who were well behaved throughout the year, or a single lumps of coal for those who were naughty. Then, after a long night of work, on the morning of Dec. 6, Sinterklass returns to the steamship and journeys back home to Spain.

It isn’t entirely clear why the Dutch consider Spain to be the home of Sinterklass – not that the North Pole makes a better a locale for the toy-making racket. The actual St. Nicholas was born and raised in Patara, a city once located on the northeast coast of the Mediterranean Sea. But there are theories that suggest how Spain got the job. One of these has to do with the Moors, people of North Africa who were once viewed as the Islamic terrors of medieval Europe.

Odd as Africa having any connection to the Santa Claus legend may sound at first, it makes perfect sense when you understand that in the Dutch tradition, Sinterklass isn’t assisted by pointy-eared elves dressed in green velvet suits, as seen on TV’s animated “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer.” According to Dutch tradition, the helper of Sinterklaas is a colorfully dressed blackamoor.”

black·a·moor | ˈblakəˌmo͝or | noun (ARCHAIC • OFFENSIVE) A dark-skinned person, especially one from northern Africa.

Here comes Zwarte Piet

Making a list and checking it twice to keep an accurate record of who’s been naughty and who’s been nice throughout the year is a monumental task, even for a magical old dude like Sinterklass. So assisting him with his gift-giving enterprise is Zwarte Piet (literally “Black Peter”), a Moorish youth with an old school feathered cap on his head and 24-karat “bling” in his earlobes.

According to tradition, Black Peter holds the ledger in which the names of every Dutch child are kept, as well as the records of their behavior. Spirited and strong, the young man also carries the sack of toys for the elderly saint. In some versions of the legend, he also brings along a bundle of switches that parents can take from to heat up the hides of mischievous children.

While the genesis of Sinterklass is generally accepted, the origin of Black Peter, though considerably more recent, is still a matter of debate. Moreover, as Europe’s relations with Black folks has varied over the centuries, so too has the nature of Peter, whose connection to Sinterklass has ranged from devilish bad cop – who tosses naughty kids into a sack and drags them off to a hell somewhere near Spain – to loyal sidekick, to noble servant, to clownish slave.

Whatever his true origin, Black Peter also clearly represents the Islamic tide that once swept out of Africa and threatened to overtake medieval Europe. The fact that he’s most often described as a Moor firmly places Peter into the historical timeline when armies from ancient Mauretania advanced into southern Europe securing a foothold that would allow the spread of Islam across portions of its then Christian and pagan lands.

Golden Age of the Moor

It was in 711 A.D. when the Moors crossed the Mediterranean Sea to reach what is modern-day Portugal and Spain. Within a decade they controlled nearly the entire region. Nine years later, Moorish contingents also crossed the Pyrenees Mountains that separate France from Spain, taking parts of southernmost France. It would take three long decades of battle before France succeeded in driving the Moors back through the Pyrenees. Their occupation of Spain, however, would last nearly 800 years (711–1492).

“Africa begins at the Pyrenees .” – Napoleon Bonaparte

Around 827 A.D., the Moors also took the Mediterranean Island of Corsica and then secured control of the island of Sicily, which they held for more than 260 years. Muslim armies made up of Moors and Arabs also sacked the Christian holy city of Rome in 846 AD, and then occupied several cities along the northern and southern coasts of Italy. The captured areas included the cities of Taranto, Brindisi and Bari, the last of these – coincidentally – being the place where the remains of St. Nicholas would later come to be enshrined.

It is this lesser-known history of the Moors (“Moros” in Spanish, “Maures” in French), as well as the Dutch involvement in the African Slave Trade, which factors largely into the figure of Black Peter. Once the ultimate bogeyman of nightmares and parental threats, this ever-adolescent Moor serves now in the neutered capacity of comic relief: A Black fool set against a white, godly St. Nicholas with silly pranks and mumbling mouthfuls of quasi Afro-Dutch Creole.

Throughout the Netherlands at holiday, it is traditional to have one person dressed up as St. Nicholas and one, two, or as many as a dozen others dressed up as Black Peter. Over recent decades, though, intense discussions about whether Peter is a racist caricature have come to divide the Dutch. The crude blackface makeovers and all of the accompanying acts of buffoonery that are used to define the character are deeply disturbing to many.

In the mid-1990s, Dutch activists began to demand that Black Peter be removed from the seasonal festivities, or replaced by a White Peter. In response, attempts were made to also feature yellow, red, green and blue-faced Peters, which met with even louder public outcry. And so, despite continued controversy, Black Peter remains a prominent figure in the holiday rituals of the Netherlands.

Straight outta Asia

“Saint Nicholas, on whom the character Santa Claus is based, was of Northern European descent,” claimed Monica Suraci, an acting spokesperson for the U.S. Postal Service. For nearly half a century, stamps that commemorate the Christmas season have been issued by the Post Office, and dozens have featured the popularized blue-eyed image of Santa Claus.

Suraci’s statement echoes the long-held belief of most Americans, including the aforementioned Megyn Kelly: Saint Nicholas was of Northern European descent. The fact is, though, he actually wasn’t. As with many of the religious figures that are today revered throughout Europe and America, the birthplace of Nicholas was Asia, the western peninsula that was once known as Asiana or Asia Minor, to be exact.

According to legend, Nicholas was born around 275 A.D. to wealthy parents in Patara, an ancient city that was situated on the southern coast of what is now modern-day Turkey. Orphaned when his parents fell victim to a plague that swept the region, Nicholas was taken into joint care by an uncle and the local Orthodox Church.

Believing that he’d been called to a life of service, when he became an adult, Nicholas donated his inheritance to the poor and joined the Orthodox monastery. Following in the footsteps of Christ, he traveled the pilgrimage routes to Palestine and Egypt. And sometime later, after his return to Patara, he was appointed to serve as a bishop in the nearby Mediterranean city of Myra.

Gold, frankincense and Myra

In Nicholas’ day, Myra (pronounced “myrrh”) was a major port city of the Eastern Roman Empire, located just opposite Egypt, on the far side of the Mediterranean Sea. In the Bible, the city is mentioned as a stopping point where the Apostle Paul, under arrest then for inciting a riot in Jerusalem, was transferred to a ship bound for the court of Rome.

According to legend, Nicholas once saved Myra from a famine when he took grain from a ship with goods being sent from Egypt to the Greek city of Byzantium. Miraculously, the stolen (or “appropriated”) cargo was never missed. In light of that daring deed, Nicholas would come to be seen as the protector or patron saint of clerks … and thieves.

Another legend states that while on a voyage across the Mediterranean, Nicholas calmed a violent storm with a prayer, making him the patron saint of sailors and travelers. In yet another tale, he miraculously brought back to life three children who were murdered by a madman and pickled (yes, pickled) in a tub of brine, making Nicholas the patron saint of children.

The very best known legend associated with Nicholas, however, laid the ancient foundation upon which the modern Santa Claus legend is based. It tells of a poor man who had three beautiful teenage daughters. The man had once been a noble but, through a series of misfortunes, he’d become nearly destitute. So much so, in fact, that he’d considered selling his daughters into prostitution, since he couldn’t provide the dowries necessary for them to be acceptable brides.

Eventually, though, Bishop Nicholas heard whispers of the despairing man’s plight and took it upon himself to devise a more saintly solution. In the dead of night, Nicholas crept up to the man’s house and climbed up onto the roof. Upon reaching the top of that precarious destination, the bishop dropped three small bags containing gold coins down the chimney.

Now, earlier that same evening, the man’s daughters had done the laundry and their wet stockings were hung at the fireplace to dry. Each bag of gold Nicholas dropped down the chimney was miraculously deposited into one of the stockings belonging to each of the girls. Or so the famous legend goes.

When the family awoke the next morning, they discovered the gifts that an anonymous benefactor had delivered to them. And due to the generosity of Nicholas (whose identity they later discovered), the man and his daughters went on to live the ‘happily ever after’ life.

St. Nicholas the Black

Centuries after the death of Nicholas, recorded as Dec. 6, 343 A.D., legends of his miraculous acts and charitable deeds continued to spread. By the ninth century in Asia and the 11th century in Europe, the bishop had become one of Christianity’s most revered figures. His tomb in Myra became a pilgrimage site and visitors would often claim to have received healing from various ailments there.

For the early Church of Europe, by the way, religious relics from Asia, including the skeletal remains of its holy men, were considered to be of tremendous value. Thus, churches were all about the business of “acquiring” relics. So much so, that on May 9, 1087, a group of men from the Italian port city of Bari raided Nicholas’ tomb at Myra and literally stole the bishop’s bones.

Back in Bari, a basilica named for Nicholas was built to shelter his remains. They lie there beneath the altar in the crypt to this day.

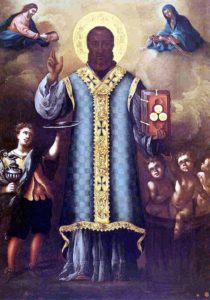

On a wall high above a 17th century altar in a side chapel at the Bari basilica hangs a painted portrait of the bishop of Myra. It is referred to as “San Nicola Nero,” which translates from the Italian as “St. Nicholas the Black.” And positioned at the center of this very surprising image is the much-heralded bishop of Myra, rendered as a bushy-bearded Black man.

The identity of the painter who created the image, dated to between the 17th and 18th century, appears to have been lost to history. But for centuries now, his art has been a spiritual focal point for regular parishioners and visiting pilgrims to the Bari Basilica.

Out of the painting, Nicholas’ eyes stare forward. The saint’s head is surrounded by a golden halo, which is symbolic of divine light. He is dressed in blue Eucharistic vestments, probably woven of velvet or silk, as is customary in the Eastern Church. His tunic is richly accented with an iridescent check pattern and a wide trim of gold brocade.

Nicholas’ right hand is raised in the gesture of benediction, while his left hand holds up the Book of Scriptures. Atop the scriptures rest three gold coins, which symbolize the legendary act that redeemed the lives of a poor man and his daughters.

On all four sides Nicholas is flanked by various figures. Christ and Mary hover in the clouds above his shoulders. To his left is the tub of brine with the three children who, according to tradition, were restored to life by the saint. Standing on the right of Nicholas is an altar boy who holds up a silver plate and a wine cruet, items that represent the ritual Communion of Saints.

The secret Santa

To say the least, the San Nicola Nero painting is a surprising image, rich with religious meaning and reverence. Much less surprising, though, is the lack of documentation anywhere that details how – in addition to popularized images of St. Nicholas with a European countenance – for untold centuries, images of another type have depicted him with physical characteristics of African or, perhaps more accurately, Black Asian populations.

Also located in Bari, tucked inside the chapel at the 11th century Norman Castle of Sannicandro, an old statue of San Nicola Nero looks out over the faithful. And elsewhere in Southern Italy, in the churches of Maglie, Mileto, Picerno and Volturara Irpina, similar images of a Moorish-looking St. Nicholas are treasured.

Beyond Italy, in the countries of Spain and Russia, where St. Nicholas is one of the most revered of all the saints, images depicting him in a similar fashion are revered. As far away as South America, at the Cathedral of San Nicolas de Bari in La Rioja, Argentina, a life-sized statue of “San Nicholas Negro” (Black St. Nicholas) has been a celebrated icon of the church since 1640.

Despite their surprisingly widespread presence, though, virtually nowhere has the existence of images such as these been documented. One cryptic sentence in the Catholic Encyclopedia will only go as far as to say that depictions of St. Nicholas in art “are as various as his alleged miracles.” And met with an old-time secret so guardedly kept, one can’t help but wonder if there are still other places left in the world where the old image of St. Nicholas with a warm chestnut complexion yet lingers.

Paco Taylor is a writer from Chicago. He loves old history books, internet search engines, and the findings of a perpetually curious mind. According to Medium, he is a pop culture archaeologist, researcher, essayist, historian, word nerd and fluent in geek speak with bylines at G-Fan, FanSided, CBR and Nextshark, who can be reached at stpaco@gmail.com. This story first appeared on Medium.