Services: Quiet Hour is Sunday, Feb. 17, 6:30-8 p.m., at Third Baptist Church, 1399 McAllister St., San Francisco; homegoing is Monday (Presidents’ Day), Feb. 18, 11:00 a.m., Rev. Amos C. Brown officiating, at Third Baptist Church

by Lynnette White

Eugene E. White was born on March 29, 1933, in Ozan, Hempstead County, Arkansas. He departed this life peacefully at his home with wife Lynnette at his side on the afternoon of Feb. 8, 2019. He was the third of four sons born to the union of the late James White Sr. and wife Maggie Stuart White. He was preceded in death by his brothers, Rev. M. Reynolds White, James White Jr. and Franklin White.

Eugene was a devoted husband of 48 years, father to his daughter Tracye, the apple of his eye, grandfather, friend and neighbor.

Eugene studied agriculture and worked in the cotton field with his father. At a young age he joined St. Luke C.M.E. Church in Ozan, Arkansas. He attended the local schools in the area during his youth.

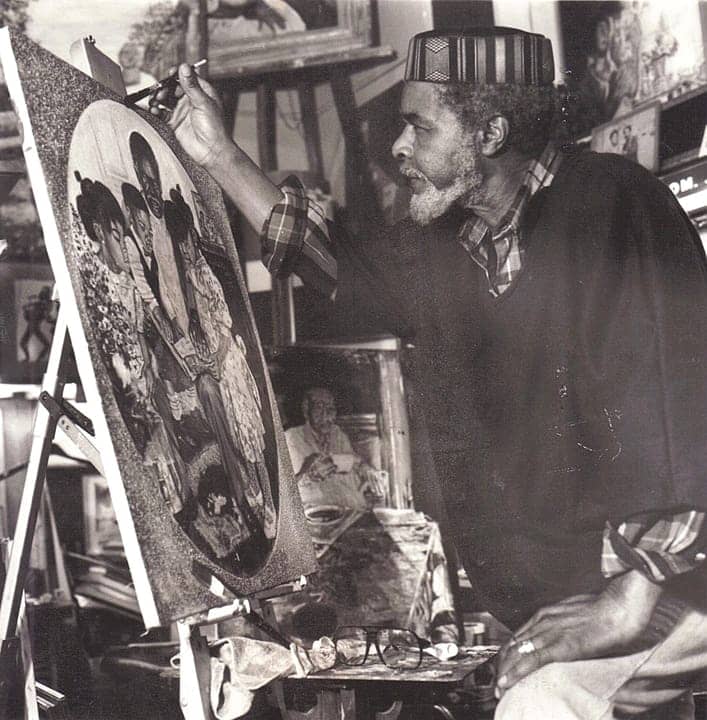

Eugene began creating art when he was a young child, though he received no formal artistic training. Although he did not study art at a university nor an art school to enhance his innate artistry, it led him to many colleges and universities across this country, and through his art he met and mingled with those of prominence and great stature as well as many everyday people as he journeyed across this country promoting himself through his works of art with wife and daughter in tow.

Although he did not study art at a university nor an art school to enhance his innate artistry, it led him to many colleges and universities across this country, and through his art he met and mingled with those of prominence and great stature as well as many everyday people as he journeyed across this country promoting himself through his works of art with wife and daughter in tow.

He eventually migrated north and found work as a sign painter and sketch artist at the Cadillac plant in Detroit in the early 1950s. He often bragged that Cadillac was the one and only job he ever held.

Accepting a higher calling for his life and continuing west, he arrived in San Francisco in 1958 and ventured into his own business. He delighted in being his own boss as he loved the independence and freedom. He opened an art gallery – the first Black-owned art gallery in the city in 1962.

White’s first public art show was in Golden Gate Park’s Hall of Flowers, sponsored by Bulart, in 1964. He has also displayed his work at such historic festivals as the original Black Expo in Chicago (1971) and FESTAC in Lagos, Nigeria (1977). In 1967, he became the first Black visual artist to display his work at the Monterey Jazz Festival.

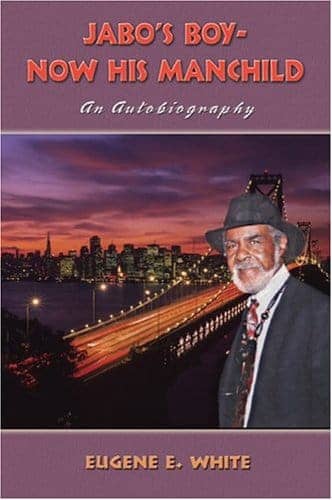

From 1975 through 2012, White published a quarterly magazine entitled KUJIONA: To See One’s Self. The magazine, distributed both locally and nationally, was intended to spread the work of African American artists, writers and thinkers. White also published an autobiography, “Jabo’s Boy – Now His Manchild,” in 2004.

In recognition of his many contributions to African American arts and culture, White received a commendation from the San Francisco Appreciation Society in 2013, and Mayor Ed Lee proclaimed July 11, 2013, to be Eugene E. White Day.

Locally he is featured in a “pin” portrait created by the Academy of Sciences that hangs over a bench engraved with his name on the Buchanan Mall. White regularly displayed his work and curated African American arts festivals at the Ella Hill Hutch Community Center throughout the ‘80s, ‘90s and 2000s. Two of his murals have graced the community center’s walls; one, entitled “Juneteenth,” depicts the migration of African Americans out of the South and is still on view today.

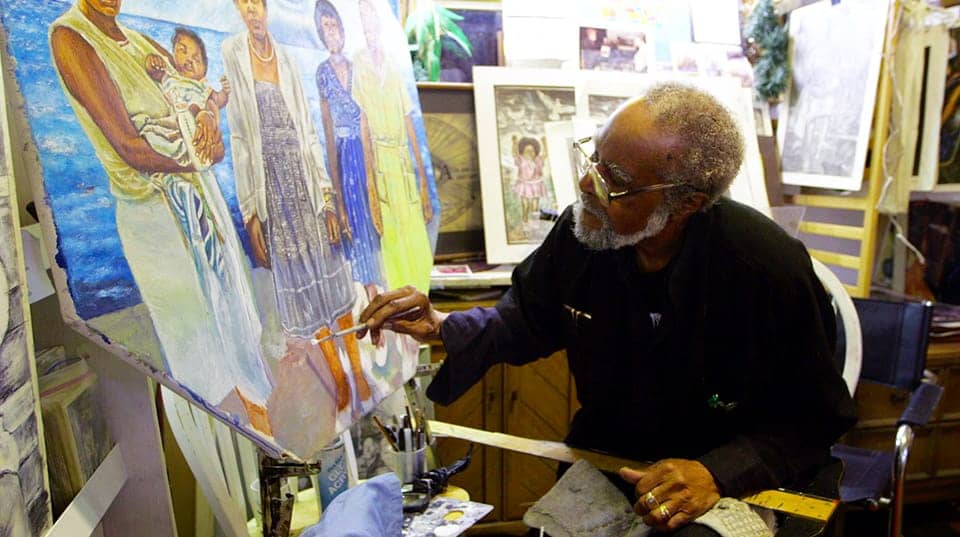

At 84, White completed a portrait for historically Black Bennett College in North Carolina. Today, White’s many paintings and prints hang in his home in the loving embrace of his wife.

His involvement in the community included politics, social,

civic and business interests.

He leaves to cherish his memory a devoted and faithful wife, Lynnette; daughter Tracye Taylor of San Francisco; grandchildren Natasha Taylor, Nykole Taylor, Grandville (Latasha) Taylor, Trevion Speed, JaMarion and JaMariae Speed; aunts Getherine Washington of Glendale, Ariz., and Precious Sherod of Oakland; nieces Magigor (Ira) Love of Washington, Ark., Dauphine (Howard) Nunn of Conway, Ark., Blondie Bradley of Hope, Ark., Shirley “Frankie” (Kevin) Johnson, Frances (Clem) Nunnerly, Cernisa (Greg) Reed; nephews Franklin “Danny” and Sharvanta, Roderick White and a host of loving cousins, friends and his Third Baptist Church family.

Eugene will be remembered for the legacy he leaves behind through his artistry.

Lynnette White, community healer and advocate, can be reached at texasgrandma54@yahoo.com.

Services for Eugene E. White

Quiet Hour is Sunday, Feb. 17, 6:30-8 p.m., at Third Baptist Church, 1399 McAllister St., San Francisco.

Homegoing Service is Monday (Presidents’ Day), Feb. 18, 11:00 a.m., Rev. Amos C. Brown officiating at Third Baptist Church.

If you do not wish to send flowers to Duggan’s Mortuary at 3434 17th St., San Francisco, CA 94110, for the services of Eugene E. White, please consider making a contribution to Third Baptist Church at 1399 McAllister St., San Francisco, or Citizen Film at 1426 Fillmore St., Suite 201, San Francisco, CA 94115 in honor of artist Eugene E. White.

Kujiona: Eugene E. White saw himself and others through art

by Denise Sullivan

Eugene E. White, the groundbreaking painter and Kujiona Gallery owner, has died, but his large canvases documenting everyday people, whether in San Francisco, where he lived and worked for over 60 years, or in his native, rural Arkansas, are a testimony to his devotion to Black art, culture and lives.

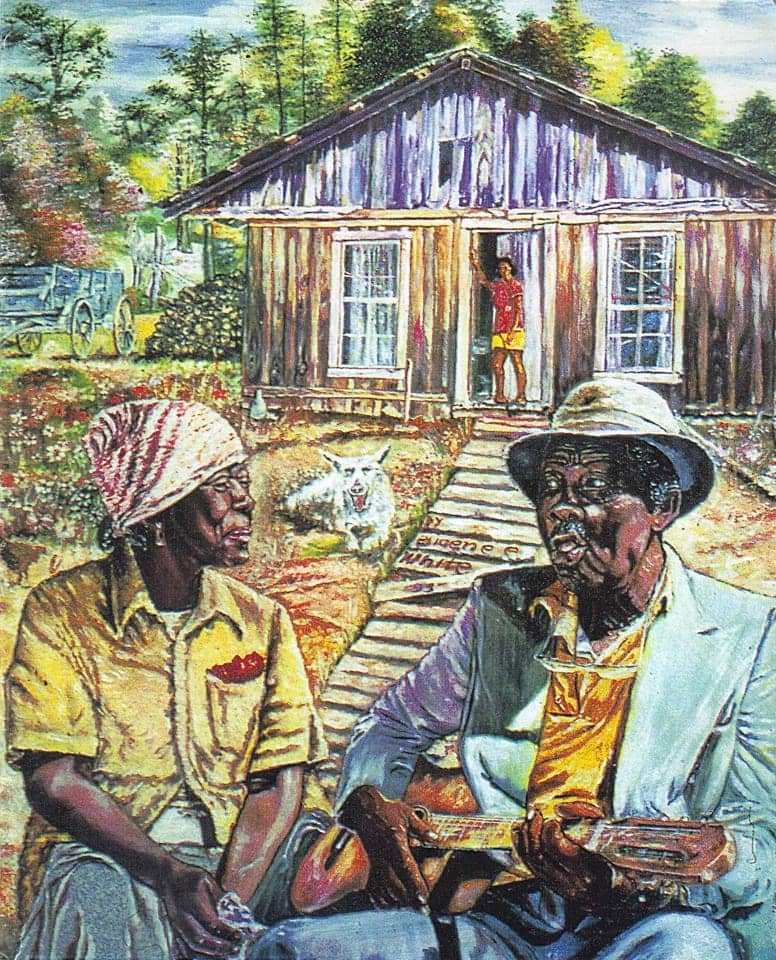

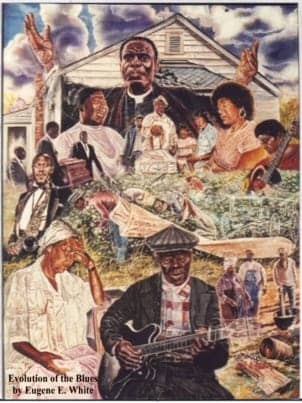

Like Charles White (no relation) and Emory Douglas, White’s paintings dating from the early ‘60s tell the stories of Black struggle and joy. He painted every aspect of the human condition, from children at play to adults at work and the elderly at rest.

These everyday moments, on the canvas and on paper, are a visual catalog of over 60 years of Black history, a subject that was dear to White: Every year around this time he would become reinvigorated with the possibility of passing on some of that history to the youngest generation.

Over the course of several interviews with him, he told me he held hope for a revolution of hearts and minds and wished for a resolution to America’s ills and troubles. He saw art as the way through – as a way to reach people.

“When I got to know more myself, I saw things differently, and that’s reflected in my painting,” he said.

Born into a sharecropping family in 1933, White lived in Ozan, near Hope, Arkansas; as a young man he worked as a fieldhand. In “Jabo’s Boy – Now His Manchild, An Autobiography,” published in 2004, he tells stories of the Jim Crow South, referring diplomatically to “adverse conditions” which were of course the horrors of segregated public life.

He had the chance to move and took it, when friends alerted him to field work in the North. He tried his luck picking tomatoes in Ohio, then from there it was on to Detroit: He’d dreamed of living in the Motor City and there he was. Though he was indeed impressed with its cultural life, racism reared its ugly head, this time at his job at the Cadillac factory where he worked doing sketches and working with electronics.

Moving on to San Francisco in 1958, he immediately found work as a sign painter and, again, as an electronics repairman. He also began to look seriously at art as a career following a debilitating car accident in 1963: Sketching became his solace during his recovery.

White’s first exhibit as a professional artist in 1964 was sponsored by Bulart. Showing at the Hall of Flowers in Golden Gate Park, he recollected in his book, “I remember how my art in this show evoked positive emotionalism from the people in attendance which sparked a stronger desire for me to paint with even greater fervor.”

“I remember how my art in this show (at the Hall of Flowers in Golden Gate Park in 1964) evoked positive emotionalism from the people in attendance which sparked a stronger desire for me to paint with even greater fervor.”

White was a self-taught artist; some call his style of painting “folk art.” And yet, there is a command of his canvas and indeed an emotionalism to the work that is undeniable. But perhaps most significantly, despite his talent, White never sold out, so to speak: He took commissions and other opportunities for hire, but he seemed to be philosophically opposed to handing off his work to an agent or gallery.

“I may be the first Black-owned gallery here, and I think I’m the last,” he told me in a 2016 interview.

White’s gallery, Kujiona (“to see one’s self”), was a treasure-trove of unapologetically Black imagery: From Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth to Malcolm X and Barack Obama, White literally painted Black history, as vigorously as he documented the everyday people from his past.

Rural life and its people were a theme: the old folks and the country people of his youth. As he got older, he talked about what his people and surrounding community had sacrificed so he could leave the cotton fields and thrive. He was eager to pass on this knowledge of farming, of elder wisdom and a connection to the earth in his paintings.

As he got older, he talked about what his people and surrounding community had sacrificed so he could leave the cotton fields and thrive. He was eager to pass on this knowledge of farming, of elder wisdom and a connection to the earth in his paintings.

In his 60 years as an artist, White took his wares on the road, traveling across the country in his RV, most memorably to Black Expo in Chicago, and across the Atlantic to Nigeria, to participate in a national cultural exhibition. In his final years, White completed commissions for the Historically Black Bennett College.

In his last gallery show in 2018, he was among other Culture Catalysts grouped at the San Francisco Arts Commission Gallery. His work remains on view at Ella Hill Hutch Center and Ingleside Presbyterian Church in San Francisco; prints of his drawings of Frederick Douglass and other Black heroes are held in the collection of the Oakland Museum of California.

His honors awarded by the City of San Francisco, the State of California and other civic entities are too numerous to mention. Suffice it to say, in 2018, the Smithsonian National Gallery had finally inquired whether White was still living and how they could contact him.

Rest assured, you’ll be hearing and seeing more of his work. Now is the time for Eugene E. White; he will continue to be recognized as a silent and steady bearer of black soul, art, beauty and truth for generations to come.

Denise Sullivan is the S.F. Lives columnist at The San Francisco Examiner and a monthly contributor to Downbeat. Contributing to magazines, newspapers, and online resources for over 20 years as an independent music journalist and arts and culture reporter, Denise’s byline has appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle, Rolling Stone, MOJO and many more. She is the editor of the San Francisco story anthology, “Your Golden Sun Still Shines” (2017) and the author of five published titles, including “Keep on Pushing: Black Power Music from Blues to Hip Hop” (Lawrence Hill Books/Chicago Review Press 2011). Visit her at https://denisesullivan.com/ and email her at denisesullivan@denisesullivan.com.