by Clement Habimana

In 1994, Jean Leonard Teganya was a 22-year-old Rwandan medical student, a hard worker whose peers describe him as smart and kind to everyone. He was in his third year of medical school, in the Faculty of Medicine at the National University of Rwanda in Butare.

Now he is in Boston’s Federal District Court, nearing the end of his trial for immigration fraud and perjury about his role in the 1994 Rwandan Genocide. If convicted, he will be imprisoned in the U.S. and then deported to Rwanda, a totalitarian military dictatorship likely to kill or imprison him for life.

Rwanda abolished the death penalty in 2007, making it easier to extradite those the government accuses of crimes, but the government’s opponents often disappear. Or their dead bodies turn up as though they were the victims of common criminals.

I am Jean Leonard’s friend and I am, with his other friends and his family, praying for his acquittal. This is my understanding of the man and the tragedy of our shared homeland, Rwanda. His case is significant to many Rwandans because the tragedy of our recent history has long been oversimplified, as it is again now on the 25th anniversary of the 1994 massacres.

Prosecution accuses Jean Leonard of lying on his immigration papers

The prosecution accuses Jean Leonard, a member of Rwanda’s Hutu majority, of lying on his application for political asylum in the United States. He wrote that the Red Cross was the only organization that he had belonged to in Rwanda, but they allege that he was also a member of the National Movement for Development and Democracy (MRND), the political party most often blamed for the 100-day bloodbath known as the Rwandan Genocide. As he himself said in court, however, “That is an opinion.”

There are many dissident accounts of the Rwandan war and genocide including Judi Rever’s “In Praise of Blood: Crimes of the Rwandan Patriotic Front,” “Rwanda and the New Scramble for Africa: From Tragedy to Useful Imperial Fiction“ by Robin Philpot, “Surviving the Slaughter: The Ordeal of a Rwandan Refugee in Zaire” by Marie Beatrice Umutesi, “Dying to Live: A Rwandan Family’s Five-Year Flight Across the Congo” by Pierre-Claver Ndacyayisenga, “How Paul Kagame Deliberately Sacrificed the Tutsi” by Jean-Marie Ngadimana, “Enduring Lies: Rwanda in the Propaganda System 20 Years On” by Ed Herman and David Peterson, and “The Accidental Genocide,” a compendium of primary-source documents compiled by former ICTR defense attorney Peter Erlinder.

Prosecution witnesses have come from Rwanda to Boston to say that they saw Jean Leonard wearing MRND clothing, attending MRND rallies, and committing rape and murder during the genocide. They say that he guided Hutu militia to Tutsi patients inside the Butare Hospital where he was training to be a medical doctor and that they were then raped or murdered.

I do not deny that these crimes were committed in that hospital, but I do not believe that Jean Leonard is capable of committing them. Neither do the friends, teachers and former medical students who came to testify on his behalf in Boston.

Four came from Rwanda and then returned at great risk to themselves. We believe Jean Leonard and his witnesses who say that, as a third year medical student, he worked to save the lives of the wounded who overwhelmed the hospital when the massacres began.

Jean Leonard’s father is a Hutu, but his mother is a Tutsi, so he would have to have wanted his own mother murdered to have participated in massacres of Tutsis because they were Tutsis.

Hutu presidents assassinated

This case must be decided on the evidence of what Jean Leonard actually did in Rwanda in 1994 and outside Rwanda thereafter. Was he in fact a member of the MRND? Did he lie about that on his immigration papers?

Did he kill or rape or help anyone else kill or rape? However, it is all but impossible to understand this case without the most basic historical context, which included the assassination of three Hutu presidents.

On Oct. 1, 1990, a division of the Ugandan Army calling itself the Rwandan Patriotic Front invaded Rwanda from Uganda and waged a four-year war to seize power from the existing government. On April 6, 1994, after three and a half years of war, soldiers assassinated Rwandan President Juvenal Habyarimana and Burundian President Cyprien Ntaryamira by firing a surface-to-air missile that struck the plane carrying them from Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania, to Rwanda’s capital, Kigali.

No one has ever been charged for assassinating the two presidents – not in Rwanda, not at the International Criminal Tribunal on Rwanda, and not at the International Criminal Court. No one has been charged despite the human catastrophe that ensued.

Habyarimana and Ntaryamira were both Hutu presidents of nations long dominated by Tutsi minorities, roughly 15 percent of the population. The Tutsis had been the two countries’ feudal and then colonial overlords. The Tutsi army that invaded Rwanda from Uganda in 1994, and the Tutsi army that assassinated President Ndadaye were all determined to reestablish their ethnic minority rule over the Hutu majority.

In Dar Es Salaam, Habyarimana and Ntaryamira had been discussing fine points of the Arusha Accords, which were – at least on the surface – meant to create a framework for peace and democratic elections in Rwanda after nearly four years of war. The missile strike shattered the fragile peace, Hutu militias began killing Tutsis, and at the same time Gen. Paul Kagame and his Tutsi army launched a military offensive to finally seize power in Kigali.

They had the tacit backing of both the U.S. and U.K., who hoped to expand their influence in the largely Francophone region, most of all in the resource rich Democratic Republic of the Congo.

I do not recount this history to deny the Tutsi genocide or exonerate Hutus who killed Tutsis between April 6 and July 4, 1994. I do so only to explain that this was the final phase of a four-year war and a long history of ethnic conflict, not an isolated 90 days in which demon Hutus killed innocent Tutsis, as the story is so often told.

The Tutsi army killed half a million or more Hutus and displaced hundreds of thousands before, during and after the Tutsi genocide.

Easter break at the Medical School in Butare, 1994

That is the context of the 1994 Easter break at the medical school in Butare, when Jean Leonard chose to stay on campus to prepare for important exams. Instead of finding quiet time to study, he saw the social order collapsing all around him after Presidents Habyarimana and Ntaryamira were assassinated.

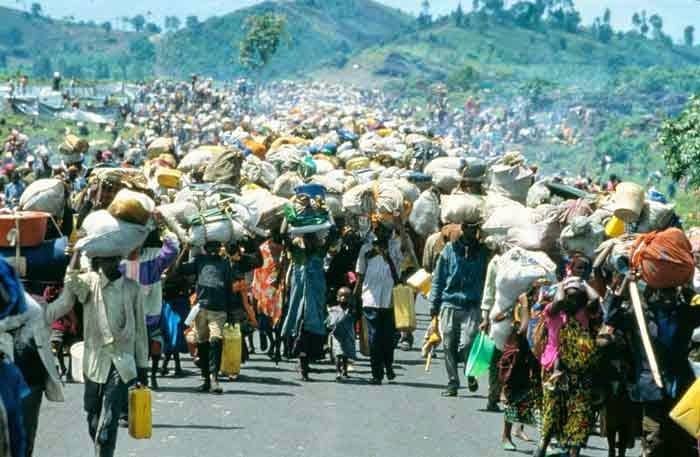

He and other third-year students had been simply observing procedures in Butare Hospital, but they were soon called to help clean wounds and administer intravenous fluids. Jean Leonard stayed in Butare to help until late June when he joined throngs of people, mostly Hutus, who were fleeing into Congo for fear of being killed by Kagame’s advancing Tutsi army.

As a refugee, Jean Leonard traveled to Congo, then Kenya, India and finally Canada, where he was reunited with his Rwandan girlfriend, who had become an electrical engineer. They married and started a family, and he found work, but Canada refused to grant him refugee status.

His troubles started when a junior immigration officer in Canada decided to accuse him of being an accomplice in the 1994 genocide. Rwandan refugees in Canada knew that this woman disliked Rwandans fleeing the Kagame regime.

Her only justification for accusing Jean Leonard was that, she said, it was public knowledge that people had been killed at the university hospital in Butare around the time that Jean Leonard was training there. Her thinking was that if he survived those killings, the killers must have left him alive because he had been helping them somehow.

She completely ignored the fact that up until she accused him, more than six years after the genocide, no one in Rwanda or outside Rwanda in any official or unofficial capacity had ever accused Jean Leonard of playing a role in the genocide. She made up a story from scratch, saying he was suspected of murder and rape at Butare Hospital in 1994.

After his application for asylum was denied in Canada, Jean Leonard faced deportation to Rwanda so, fearing for his life, he walked to the southern Canadian border and into the United States and applied for political asylum there. In light of the Canadian decision, and because Jean Leonard was at the hospital during the genocide, U.S. authorities decided to bring a case against him.

Prosecution weaknesses

An investigator for the prosecution recently testified that he had traveled to Rwanda during the summer of 2016, but that he did not speak Kinyarwanda or French, the languages of Rwanda during the 1994 genocide, so he had to hire a translator. Defense investigators later found that this translator was not certified to do court translations. Furthermore, the investigator’s hands were tied because the government would not allow him to record the interviews he conducted there.

The most puzzling aspect of the prosecution investigator’s testimony was his description of how he had identified witnesses. He said that he had Googled the first prominent witnesses, who then led him to others.

However, he could not explain what sort of Google searches he had done or why. He also failed to mention that his first witnesses were employees and contractors of the Rwandan government, or that the government would like to see Jean Leonard convicted and deported because they cannot tolerate a complex or even nuanced narration of our country’s history.

In the past 20 years, Rwandan President Paul Kagame has tightened his totalitarian grip on the country and imprisoned many Rwandans for speech crime.

Halfway through his testimony, the prosecution’s investigator stated that for transportation, he had rented a car from a rental company whose name he did not want to disclose, and that drivers did not help or interfere in his investigation. However, the defense attorney confronted him with a trip report from the summer of 2016 in which he had stated that his driver discussed witness testimony with him.

In dictatorships like Rwanda, it is well known that visiting officials and even tourists are carefully surveilled by government spies and with high tech equipment.

Defense and prosecution will deliver their closing arguments on Friday, April 4. The jury could convict or acquit Jean Leonard within a matter of hours, but that is unlikely after a four-week trial. We, his friends of family, pray that he will walk free after two years in prison, but either way we will continue to stand by him as well as we’re able and continue to call for truth and reconciliation in our homeland, Rwanda.

Clement Habimana can be reached via editor@sfbayview.com.