Review by Wanda Sabir

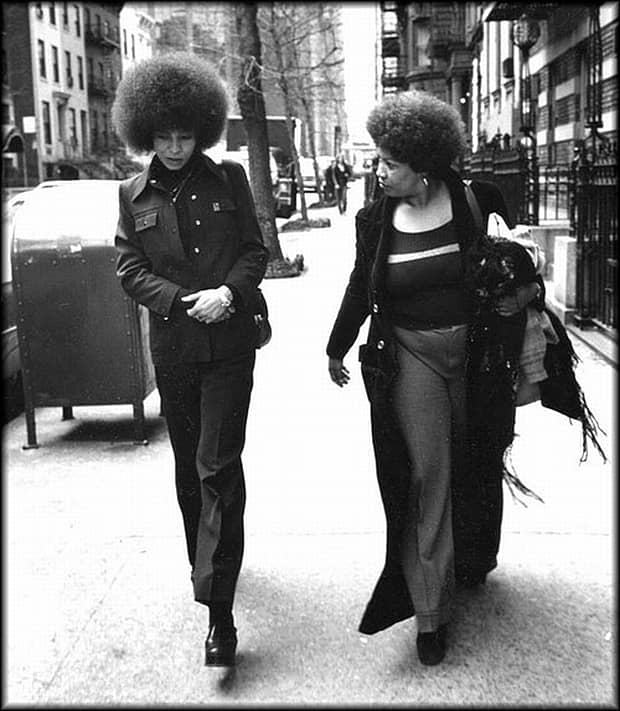

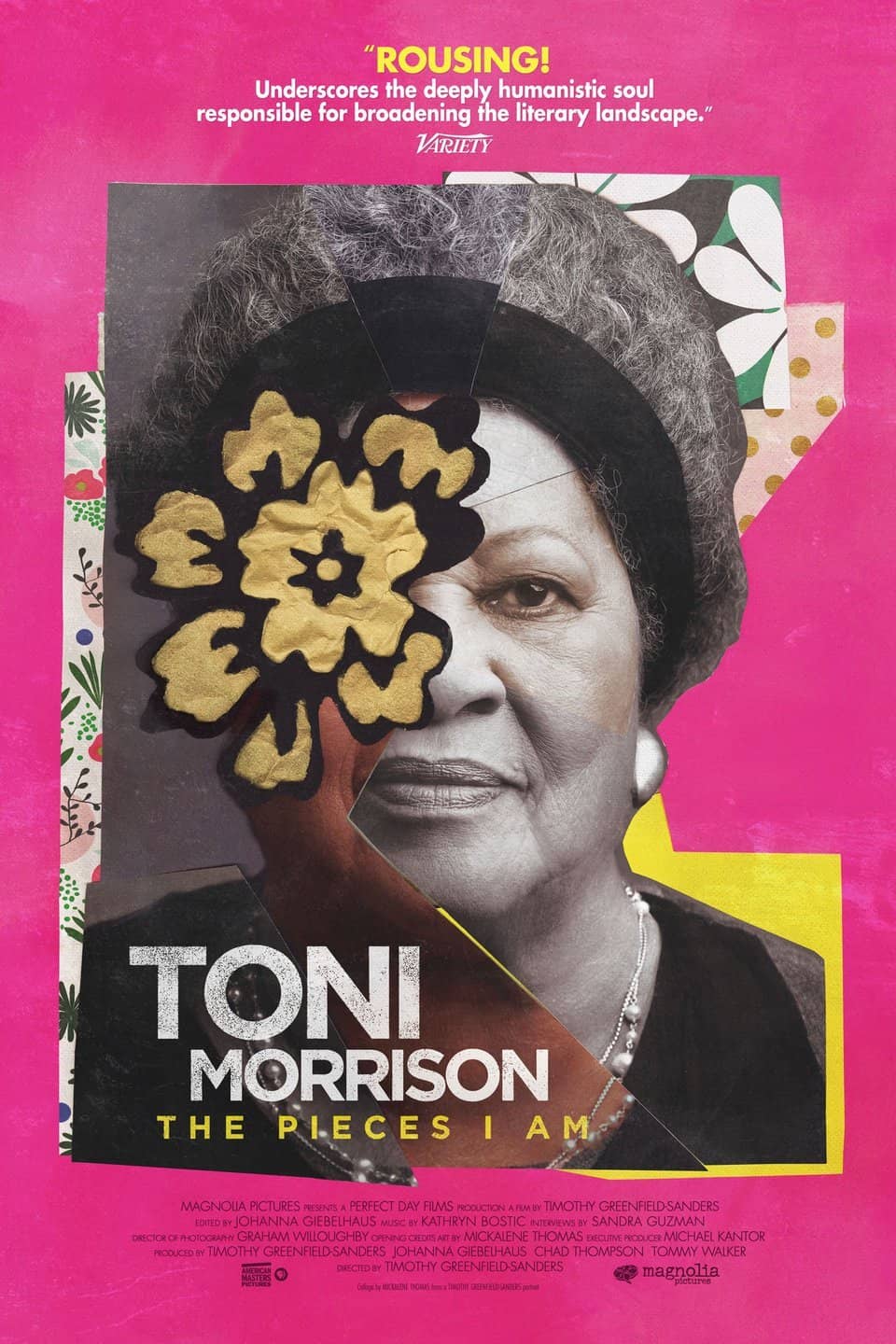

It’s a film we’ve all been waiting for, even if we didn’t know we were holding a collective breath beyond hope that it would someday be made. With an all-star lineup of guests who rave and even weep over a life well-crafted like the characters that haunt and explicate a gene pool too deep to tread lightly – Timothy Greenfield-Sanders’s “Toni Morrison: Pieces That I Am” (2019), 120 minutes, is that work. The director shares an intimacy on screen with an artist, Nobel Laureate, mother, Daddy’s girl, whom we know from “The Bluest Eye,” “Sula,” “Song of Solomon” and “Beloved” to “Paradise” and “A Mercy.” Some, like Angela Davis, Oprah Winfrey, Walter Mosley, Sonia Sanchez and her editor, Hilton Als, know her as friend.

In a work that is as lovely a cinematic journey as it is a pleasure to listen to and discover more about this very private yet public figure, this may be a work Greenfield-Sanders cannot top. Morrison’s mother’s family moved from Greenville, Alabama, to Lorain, Ohio, where Morrison was later born. Her dad grew up in Cartersville, Georgia.

Morrison speaks of her community as a mixed race town where all the kids played together and the families got along. The second eldest of four, she spoke of going to Howard University and then Princeton so she could have fun, perhaps too much fun away from her mother’s watchful eye.

The author’s journey to New York where she was hired by Random House is a sight mere words cannot convey. Imagine a self-possessed Morrison with a pipe, the only woman in photos with white male colleagues; that speaks volumes about Morrison’s autonomy and self-assurance. In one scene she learns that women editors are making less than their male counterparts. In the next she tells her supervisor, “I am head of household just like you.” Her pay is made equitable immediately.

This example of Morrison’s non-sexist or racial nonsense is repeated often in “Pieces that I Am.” An epic life, what makes this film even more remarkable is the use of fine art to illustrate the journey. From Jacob Lawrence’s “Migration Series” to Charles White, Lorna Simpson and Hank Willis-Thomas, the work explores a writer’s life and the reciprocal nature of this medium. The film was released locally and nationally in June and will also debut on KQED locally in the American Masters Series.

The director and I had an opportunity to chat briefly late June about this work.

Wanda Sabir: Oh, my goodness. Your film is so marvelous.

Timothy Greenfield-Sanders: Thank you.

WS: It is such a tribute … long overdue to this fabulous woman.

TGS: Long overdue. I agree with you.

WS: Totally amazing. Were you put on this planet to do this?

TGS: Sometimes they happen: strange things that are unexplained. I guess maybe I was put here to do this.

WS: I’m wondering about the title because there are so many aspects of her life that you could have zeroed in on, but this is the story that you both choose to tell.

TGS: The title is a line from [the novel] “Beloved.” We were searching really for a subtitle, and when I saw that, it all came together kind of perfectly because it relates to Micalene Thomas’s wonderful opening where the pieces of Toni come together. It relates to the way Toni writes. It’s not linear; she comes from many different directions, and it also relates to the concept of the film, which is that these are the pieces of Toni Morrison, the single mother, the editor, you know, the teacher, and of course the great writer and Nobel winner.

WS: Right, right. That’s so true. As I was watching the film last week. I took so many notes.

TGS: It’s a really dense film in that sense. There is so much to think about. We kind of lure you in because Toni is so loving really in the film. You know, you love her. I think that once you start to watch it, all of a sudden there’s so many things to think about, right?

WS: Yes, there are. I was wondering if you could tell me about your Toni Morrison, and what pieces of her didn’t make it into the film. I just love learning about her family and their moving – her grandmother, having to pick up the girls and move to Lorain, Ohio. Her mother and father sound so powerful. Those stories are so riveting.

TGS: She wonderfully contrasts her parents in a very vivid sense of their personalities. I think, in the film she says my mother looked at each person as an individual and she didn’t look at color or anything. She just looked at them as like, you know, who they were and if they were a good person or not. And her father was very strident. Different, you know, but for good reason. I mean he had come from some place of horror and seeing terrible things.

WS: Right, right. Definitely and then I wonder if because her father was such a strong presence in her life if this is why she was able to function in such a male-dominated field (publishing).

TGS: It’s a very interesting point you bring up. It’s not specified in the film, but I know from knowing her and from hearing her talk that her father had tremendous influence on her and also he believed in her. I think at a very early age her father adored her and realized how brilliant she was. I think this was a man who really knew, [the way a parent knows which of his] children are special or exceptional in some way. I think [he knew she was exceptional and I think] that probably stayed with her whole life that this strength that she got early on from him. I’m happy you brought that up. Thank you.

WS: Here’s this woman smoking a pipe and she’s the only woman among all these men. Some people might be like wow all these powerful white men. Aren’t you like lucky? The way she saw it was they are lucky to have me.

TGS: “I was more interesting than they were,” she said.

WS: Exactly. She holds her own and claims her space and doesn’t compromise. I mean, I love it. She was not about to take less pay for the same job.

TGS: All of the lessons we try to teach today. She was a pioneer. She was doing that when it was really hard.

WS: Right, right. Talk about how you frame your subjects with your camera, both still camera and your film camera. It’s intentional the way you shoot and I was thinking about Brian Lanker, the photographer whose work, “I Dream a World: Portraits of Black Women who Changed America,” had a stop at the Oakland Museum of California.

Lanker said when he was on tour with the exhibit, he placed his subjects so that he was looking up to them, as opposed to down. It was a position of reverence and respect. Talk about your philosophical intent in framing Morrison the way you do as well as the people who are talking about her. I also noticed positioning and power dynamics within the framing as well.

TGS: I’m a photographer and a filmmaker. My photography is distinctive. I have a look that is really a simple backdrop and one light and direct to camera gaze. That is all purposeful, because what I’m trying to do is focus on the person not on my fancy lighting [and] not on some environment that they’re in. I’m trying to say look at this person here. Look into his or her eyes. That’s kind of my intention, and I translate that look to film so that when you’re looking at these interviews, you’re getting the kind of the beauty of my portrait lighting, but you’re really focusing on that person.

And what I what I try to do in this film is, if you noticed, Toni is the only one who’s talking directly into the camera. The others are talking off camera. There are talking about her, but she’s talking to us. That was very conscious on my part. It was something I’ve never seen in the documentary where you combine those two – you either decide one way or the other. You don’t do both.

I felt that by letting Toni be the only one talking to camera, it also gives her agency and it makes it Toni’s story. She’s the one looking at us. It becomes overwhelmingly clear that she’s telling the story.

WS: It is really clear. The work looks like she is directing it.

TGS: As a white male director, I’m very conscious of my white male gaze. I surrounded myself with people who were able to kind of bring voices to the production, to the film and at the same time, you know, making sure that by shooting it the way I did, Toni is really telling her story.

WS: You have a series on identity: “The Black List” became three feature films, followed by the “Latino List: Volumes 1 and 2,” “The Out List,” “The Women’s List” and “The Trans List.” There are eight films in total. I was just wondering how this film is like a culmination of that work and what could follow this?

We both laugh.

TGS: At the moment. I’m not even thinking about like what to do next. But when you look at this film, when you see the 12 people in it, they all deserve documentaries – such as Sonia Sanchez, Walter Mosley, Angela Davis and Farrah Griffin … all these people are remarkable. There are so many great stories out there to tell but the Toni one was very personal to me because she’s been such an influence on all of our lives, but on my life in particular. She was the one that got the Blacklist idea. I give her credit for the whole series. It is based on an idea that Toni had.

WS: Tell us about that first shoot 38 years ago as you set up without assistance in your SoHo Studio.

TGS: I was asked in an interview: Do you remember what [Morrison] was like back then and I said, I remember how confident she was as a person. When you’re a photographer looking at the subject, you’re trying to read the subject and see if the person is nervous. Do I make need to make him or her feel better? What do I need to do to get trust from the subject? And I remember with Toni she walked in smoking a pipe. She was confident. She was clearly like, here we are, let’s do it. It was remarkable. I remember that very well.

“Morrison holds her own and claims her space and doesn’t compromise. She was not about to take less pay for the same job.”

(The director doesn’t share that he walked Morrison to the bus stop because he knew she’d have difficulty getting a taxi from his East Village photo studio. She never forgot the favor and when Vanity Fair magazine wanted to do a profile, she insisted the editors call him. Fast forward, Timothy Greenfield-Sanders is on the masthead.)

WS: Another aspect in this unique film is the art. It is amazing. I recognize Charles White, Kara Walker, Kerry James Marshall. Jacob Lawrence’s “Migration Series” follows Morrison’s family north from Alabama. To let these famous Black artists illustrate a film is so beautiful.

TGS: I have never seen it in a film. I always thought, why aren’t we cutting to a painting? Sometimes you don’t have a photo. I think that what we did here was so special because it [not only] brought 20-something African-American artists’ work into the film, which was wonderful, but it also was about a feeling that these images give not just illustration; they give you a mood and an understanding of what was being said.

So when Sarah Griffin says, “There’s a whole world out there that white people don’t even know about,” and we cut to the Kerry James Marshall “Pastime” painting, what could be a better image than that painting? It’s just a flawless piece of filmmaking if I do say so myself. (The director coughs and chuckles modestly. I join him.)

(I agree, yet it is Rashid Johnson, artist and friend of the director [not the same person as Kevin “Rashid” Johnson, whose essays and art work regularly appear in the Bay View], who introduces him to artists like Kerry James Marshall’s work, who generously makes his work available for the film when asked.)

It was fun to do that and I have a long history in the art world. I photographed for 20 years the world of artists and art dealers and critics. I have 700 portraits at Museum of Modern Art in their collection, so it’s a very big part of my life. I studied art history at Columbia, so I know a lot about art and a lot of artists and many of them in the film like Kara Walker and Lorna Simpson. I actually photographed Jacob Lawrence before he died.”

WS: (I have to stop the director and take a breath before continuing.) Jacob Lawrence?! Wow –

Tell me about Mickalene Thomas’s opening collage.

TGS: Well Mickalene Thomas is a very important contemporary artist. She’s one of the artists I did not know personally and I pulled an Oprah, you know; I just found her phone number somehow, I called her and I explained what we were doing and she said “I’m in,” that quickly.

I think that was the reaction of almost everyone I reached out to. Everyone felt that way about Toni. Mickalene is known for her collage work, so I thought there was a way for her to do some kind of piece for the opening based on my photographs.

We gave her, oh gosh, hundreds of images to play with – every photo I’d taken of Toni – and just saidgo to town on this. Four months later, we were about to send the film to Sundance to try and get into the festival and I called her I said I need something early next week. She sent the marvelous piece we finessed into that opening that you see.

WS: Remember when Toni Morrison’s son passed, Slade. In the film it’s both personal and public, in the way it is choreographed so to speak. I just love hearing from her friends, because you can say that the people that are talking about her are both friends and Morrison groupies. Oprah is so dramatic and Sonia Sanchez, when she starts crying, I start crying too. Oh my. And then there’s Angela Davis. Like who knew that Toni Morrison was the reason why we have her autobiography at 28?

We think, Angela Davis was really 28 at one point? (The director and I take another moment to laugh). Look at what she is doing at 28! Then Muhammad Ali? Oh, my goodness. Walter Mosley sitting around the kitchen table just sort of chopping it up, as they say. It is so special.

TGS: They understand [her gift]. I think it was Paula Griffin who said, “She means so much to us.” I love that line.

WS: Right. It was so funny, you know, to see my younger daughter TaSin’s friend Hank Willis Thomas in the film. They were in the same graduating class at California College of Arts and Crafts. My daughter a BFA in photography, Hank an MFA.

TGS: His mother Deborah Willis is a friend of mine. She’s fabulous. I love that piece of his too. Isn’t that sort of perfectly placed as well, that kind of divine image to show there.

WS: Elizabeth Catlett. You have a who’s who. Some artists are making their appearances as spiritual beings – theirs is an Aṣé to their work and their spirits and to what they’ve done for our people. [“I love that,” the director says.] But it’s also a nice Aṣé to Morrison – they are tipping their hats.

TGS: It is and it is intentional and [I love] to hear you saying that. I have watched the film many times with audiences; and certain audiences just really get it and there’s always someone in there who’s whispering under her breath or his breath, “I’ve always liked Elizabeth Catlett … Charles White … Kerry James Marshall.” I love that when that happens. They are part of a dialectic these images.

WS: How long did it take you to pull it all together? I mean, of course not all 38 years, but this particular project?

TGS: It’s really about five years. First talked to Toni, asked her if she would consider it. She didn’t say no, which was a good sign. Then finding the funding for it [when she approved], assembling the team and choosing the people to be in it and then really two years of editing is an enormous amount of work: researching, finding all this material in high resolution and getting the licenses for it. All of that is just a tremendous amount of work.

WS: Hmm. So how did you decide – because I’m sure everyone you asked to talk about Ms. Morrison probably said yes, so how did you end up with this select group of people? I read that you had a Peter Sellers’ interview that didn’t make the cut. I remember the Sellers-Morrison symposium on “Desdemona” at UC Berkeley with Rokia Traoré (who played the lead). Toni Morrison, who wrote the libretto, participated via skype.

TGS: I was very careful not to interview anyone who wouldn’t make it into the film. I think it’s unfair to just interview lots of people when they give you their time and their energy. Peter, I feel such guilt for. We have a fabulous piece on Shakespeare and Toni with Peter Sellers, and we pulled it because it was an easy seven minutes to pull out of the film – and I haven’t for the DVD extras and stuff – but I try to really just invite people who I knew I would include in the film in some way.

WS: “Desdemona” was really amazing. And I was so excited when I thought Morrison was going to be in the house, because she comes here. She had come to the Bay Area because she’s a friend of the Marcus Bookstore founders here. She comes to do fundraisers for them. I think Marcus Books the oldest Black book store here in Northern California.

TGS: In this seven-minute clip we also asked people what their favorite Morrison book was.

Angela Davis is “Desdemona.” Isn’t that fascinating? She said that when she saw the production it was the most moving thing she’d ever seen in her whole life.

That’s in the DVD extras. I wish we could have put it in the film but there’s so much that we could that other stuff that we had that we had to make decisions. As the director you’ve got to say, “This is the length it’s going to be; this is the way it’s going to be structured and I don’t think there’s room for that.” It’s to make those choices.

WS: “Toni Morrison: Pieces That I Am” (2019) is a classic similar to “James Baldwin: The Price of the Ticket” (1990), directed by Karen Thorsen. In “Price of the Ticket,” Toni Morrison speaks at James Baldwin’s funeral. Other more recent series classics are 2018 Peabody winner, “Lorraine Hansberry: Sighted Eyes/Feeling Heart” (2018), directed by Tracy Heather Strain, and Peabody Winner for 2017, “Maya Angelou: And Still I Rise” (2017), directed by Bob Hercules and Rita Colburn Whack.

“Toni Morrison: Pieces That I Am” opened nationally at the end of June and continues in Bay Area theatres such as Opera Plaza, San Francisco; Summerfield, Santa Rosa; and Albany Twin, Albany.

Bay View Arts Editor Wanda Sabir can be reached at wanda@wandaspicks.com. Visit her website at www.wandaspicks.com throughout the month for updates to Wanda’s Picks, her blog, photos and Wanda’s Picks Radio. Her shows are streamed live Wednesdays and Fridays at 8 a.m., can be heard by phone at 347-237-4610 and are archived at http://www.blogtalkradio.com/wandas-picks.