Busting down walls and opening doors through art, culture and education at the first annual Ratcliff Award celebration benefiting SF Bay View and Prison Focus

by Kim Pollak, California Prison Focus

“The Ratcliffs provided the empowerment that kept my fire alive.” – Min. King X

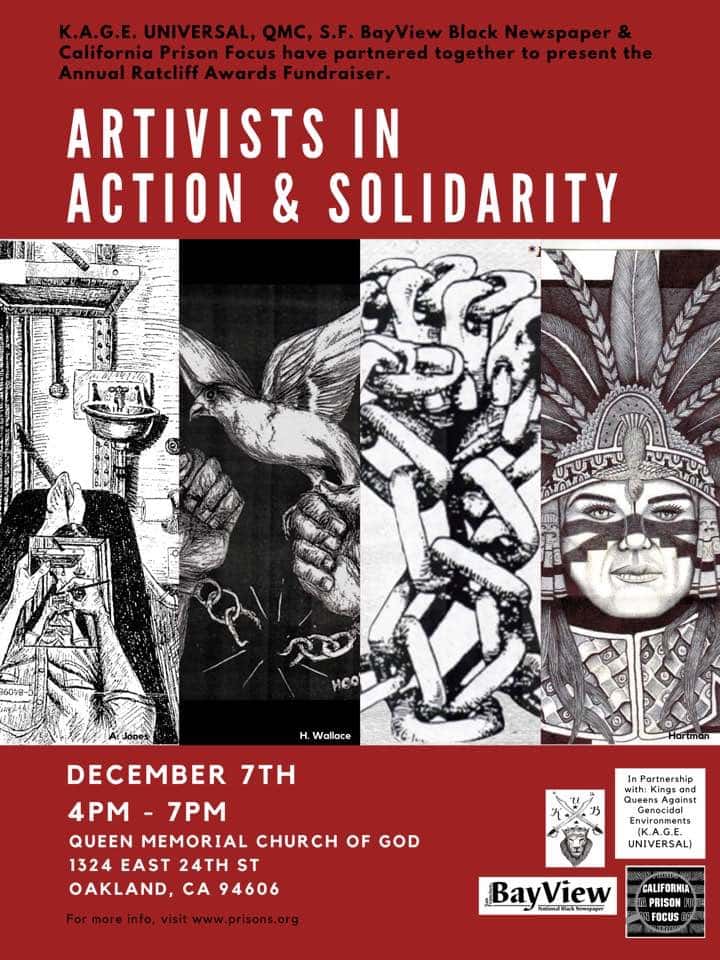

The Artivists in Action and Solidarity event coming up on Saturday, Dec. 7, 4-7 p.m., at the Queen Memorial Church of God in Oakland, 1324 E. 24th St., Oakland, emerged from a powerful alliance and special bond between two Bay Area-based newspapers, SF Bay View and Prison Focus, a quarterly publication of Bay Area non-profit California Prison Focus, and William E. Brown, aka Min. King X, the recently released founder of a prison-based anti-hostility group called KAGE – Kings and Queens Against Genocidal Environments. The event offers a special opportunity to honor the legacy of SF Bay View publisher and editor and unsung heroes Willie and Mary Ratcliff by presenting the first annual Ratcliff Award to another unsung hero within our community.

Min. King conceptualized this art-centered event from within the confines of his cell, with plans to implement both the event and the KAGE program, described in more detail below, outside the walls upon his release. Both the program and the event will use art to shine a light on the hidden atrocities of prison, to gain the release of his still imprisoned elders, mentors and loved ones, to support imprisoned artists, and to support the two publications that inspired and empowered Min. King throughout his journey. Proceeds will be raised through a silent prisoner art auction. Imprisoned contributors will receive compensation for their work, while the rest will go to SF Bay View and California Prison Focus.

Who is Minister King X?

William E. Brown is a profound political hip hop artist, revolutionary writer, ordained minister and Oakland community member, who first encountered California’s brutal judicial system at 8 years old when he was arrested for trying to steal a 35-cent bag of chips from a vending machine.

William, a manchild of the ‘70s, was raised by his father, a singer, musician and artist, who worked hard to take care of William and his four younger siblings. While there was no shortage of love in William’s household, he experienced firsthand the suffering caused by a deprivation of basic necessities. Inclined to care for and protect his father and young siblings, William learned how to navigate within a world of unmet needs.

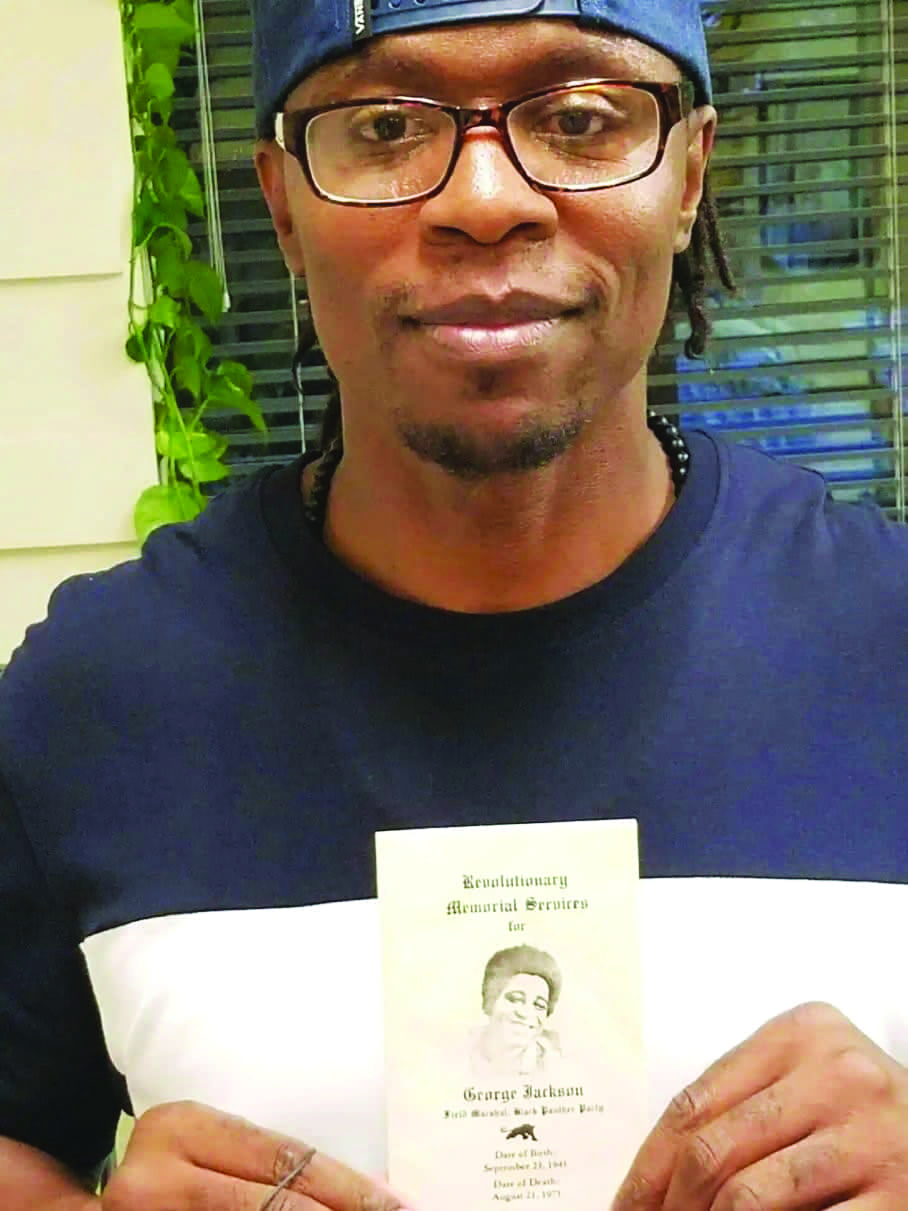

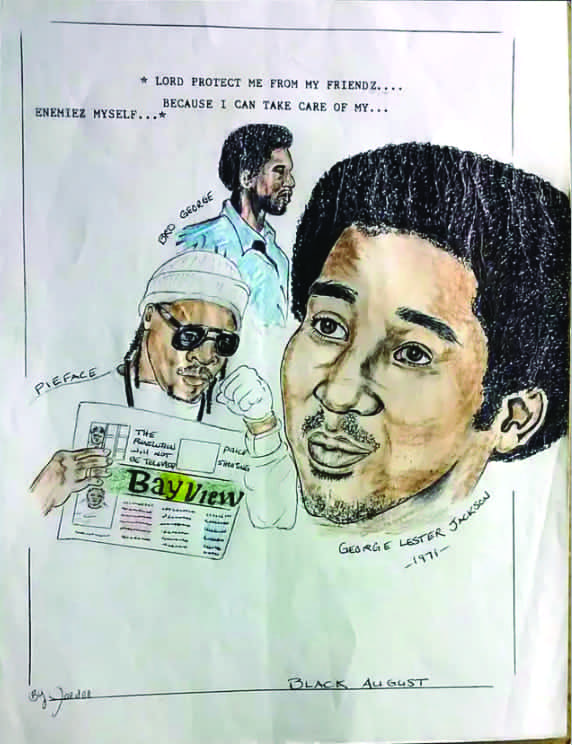

This eventually led him to a series of bank robberies “to support the poor peoples’ movement,” he states. With his stolen loot, William bought books and shoes for his siblings and helped his father and friends with rent. “A Black Robin Hood,” he called himself. As a flourishing hip hop artist known as Pyeface, aka the George Jackson of rap, William also supported his passion for the arts.

Eventually William was caught with his hands in the cookie jar, and while luckily nobody was physically hurt, he was sentenced to six years in federal prison. Only months after being released from the feds, King found himself accused of a bank robbery. While he knew the perpetrators and had in fact provided them with tips on how to pull off a bank robbery, he did not directly participate in the crime.

Nevertheless he was arrested, tried and convicted, and subsequently sentenced to 16 years in prison. While in prison, mostly in solitary confinement, he became an outspoken political writer and strategic agitator, which incurred constant retaliation from prison guards as well as a five-year extension added to his original sentence.

Min. King’s close friend and fellow artist, Donald “C-Note” Hooker of DaReal PrisonArt, explains: “While violence is a way of life in prison, behind the wall, Pyeface unwaveringly stood for peace. This didn’t endear him to many, especially those who profit from racial, gang and prisoner on prisoner discord.”

As a developing jailhouse lawyer, King explains, “challenging the system became a lifestyle.” It was Min. King’s knowledge of the law and refusal to succumb to prison officials’ attempts to degrade and silence him that led guards to plant a weapon on him in 2010 and subsequently sentence him to three consecutive years of solitary confinement in one of California’s notorious Security Housing Units (SHUs). With no staff accountability or legitimate due process, it can take the contempt of only one guard to find oneself arbitrarily condemned to solitary confinement for months or years.

Prior to being transferred to SHU, King was funneled through a “short-term” Administrative Segregation Unit (ASU), also solitary confinement. While ASU terms are generally shorter than SHU terms, in ASU people don’t have access to their property, including TVs or radios. It is often an individual’s first time experiencing torture by extreme sensory deprivation, and suicide rates are high.

Knowing that he faced three years of solitary confinement, King made the decision to better himself through study and meditation so that he could more effectively challenge and ultimately change the system and contribute to the strength and wellbeing of his community, both inside and outside the prison walls. He rejected materialism and decided to “play chess versus checkers,” using strategic foresight at all times.

In SHU, King found himself surrounded by some of California’s greatest thinkers, including OGs who had survived decades of solitary confinement through self-education, empowerment and a deep sense of soul, self and determination. These men included Sitawa Nantambu Jamaa, Mutope Duguma, Heshima Denham, Michael Zaharibu Dorrough, Paul Redd, James Baridi Williamson and Louis Powell, among others.

Several of these men were members of the Short Corridor Collective, which organized the massive California Prisoner Hunger Strikes of 2011 and 2013, and created the historic Agreement to End Hostilities in 2012, a document created to counter CDCR’s efforts to sow discord, violence and division. The Agreement to End Hostilities promoted the very thing Min. King had already come to embrace, solidarity as an act of resistance.

It was while sitting alone in a 6-foot-by-9-foot windowless concrete tomb for 23 hours a day that Min. King transformed his tapestry of experiences within California’s judicial system, his political education and his quest for freedom, justice and equality into what became the foundation of an idea that grew into KAGE, an inside-outside prison program promoting peace and unity among racial groups.

Using art and culture and a political backdrop, KAGE “promotes peace as ‘the new cool,’” as I personally reported in the Prison Focus newspaper (Spring 2015, Issue 45, page 7). KAGE is building consciousness and unity among different racial groups and deterring people from feeding into their own shared oppression. Because solidarity threatens the Department of Correction and Rehabilitations’ status quo, CDCR refused to recognize KAGE, claiming it was gang-driven. Ultimately CDCR failed in their pursuit to squash the prisoner-driven solidarity movement, which has been growing informally behind the walls ever since.

Discovering the San Francisco Bay View and Prison Focus Newspapers

One day in 2011, Min. King was called from his cell to engage in an interview with a California Prison Focus legal activist. King and a handful of other men were stripped naked, made to squat and cough, then once dressed again, shackled and paraded through the corridors to adjacent holding cells near the visiting area. Once in the cell, while awaiting their turns, the waist and wrist shackles were temporarily removed, though their ankles remained shackled. Through the cracks under the doors and walls the men had a rare opportunity to communicate.

In response to Min. King’s legal activity, an OG in the holding cell next to Min. King, named Woody offered some valuable advice: “Pyeface, contact the media because otherwise these people [CDCR] are going to ostracize you and attempt to sabotage your concerted legal efforts.” With that, he slid a copy of the SF Bay View newspaper under the door.

Then, a jailhouse lawyer in the next holding cell over named Edward Furnace, also awaiting an interview with California Prison Focus, offered King some strategic legal advice. He said, “Lil bro, you’re going to have to sue these people, so get you a ducat for the law library and learn how to file a 42 U.S. Code § 1983 civil action for deprivation of rights.” Furnace encouraged King to stand firm in his legal pursuits: “You can never allow them to break you,” he said.

Following King’s investigative legal visit with California Prison Focus, Min. King was given a copy of the Prison Focus newspaper. Thus equipped with both a copy of the SF Bay View and Prison Focus, King went back to his cell and read the two newspapers cover to cover. “I couldn’t sleep that night because ideas were jumping inside of me. That was radical journalism. I was beginning to understand how much power and respect there is in resistance,” King explained.

Over the next few years, Prison Focus, SF Bay View and the relationship that Min. King developed with the Ratcliffs changed his way of thinking and his life. “SF Bay View and Prison Focus added on to my New Afrikan world view. I already had ideas about fascism and feudalism, but those papers broke it down. Everything started to crystalize.” King explained.

“They taught me how to manifest my ideas, how to resist instead of react, how to more effectively challenge policies and use the law. I started paying attention to DOM, the CDCR Department Operations Manual because it was referred to in the papers.

“When I saw other people’s stories in the papers, I started wondering if I could write my own story to be published. Then I was seeing the artwork – like Kevin Rashid Johnson’s – attached to the writings. Through the paper I felt connected to his struggle, all the way in Texas.”

King was reminded of what Suge Knight, former producer for Tupac Shakur, told him when they were celled together in the feds over a decade earlier when asked what the key was to his success. “Presentation brings power,” Suge told Min. King. To Min. King, this spoke to the power of imagery, something he eventually read more about in Robert Greene’s book, “The 48 Laws of Power.”

“Law 37: Create Compelling Spectacles: Striking imagery and grand symbolic gestures create the aura of power – everyone responds to them. Stage the spectacles for those around you, full of arresting visuals and radiant symbols that heighten your presence. Dazzled by appearances, no one will notice what you are really doing.”

“So once I understood the ‘power of symbols as a way to rally, animate and unite the troops,”, King explained, “and inspired by my father, and the likes of Rashid, Michael Russell and Danny Troxell, I also started to use drawings to tell a story … Those papers started changing my mind, and through them I found my voice.”

Expanding on his relationship with Mary Ratcliff, Min. King explained that “Mary was always inclusive. She made me feel part of a collective. When nobody else wanted to hear it, Mary always listened. If she didn’t include my writing in the paper, I would still receive a letter back. If I didn’t receive a letter back, I would receive the paper … She was my connection to the outside world.”

“Mary felt our struggle.” Min. King continued. “She understood how much I loved my brothers who didn’t get to meet me.” Here Min. King refers to the men with whom he was housed in the SHU solitary confinement units. For three years he communicated with his comrades through vents and drains, but had never seen their faces.

In summary, Min. King stated, “Those papers made me want to be on the right side of history, and that’s where I’ve been ever since.”

When Min. King was finally released from SHU solitary confinement in 2014, he returned to the mainline with a message and a mission. He had made assurances to his elders still locked up in solitary that he would “do everything I could to get those guys out, to get the word out, to liberate their voices and liberate them.”

Min. King, Pyeface, was still respected by the younger generation though he was by then over 40 years old. He vowed to act as a liaison between his elders in solitary confinement and the youth in general population, who had yet to be politicized. “I broke it down for the youngsters and showed them how to fight the system in ways that would not be to their personal detriment.” He told them what was going on in SHU and why they needed to band together to get their elders out of the hole – why they needed them on the yard.

Min. King was determined to bring his anti-hostility teachings, refined during his years in SHU, to the mainline. He knew that to reach the youngsters, this would have to be done through music, art and pop culture. He and a handful of his peers were determined to take the words of the Agreement to End Hostilities and use art to bring the words to flesh.

Inspired by past revolutionary leaders, like George Jackson, who had organized small study groups on the prison yards in the ‘70s, Min. King helped to create multi-racial study groups that promoted peace. “Nobody wants to be stabbing people,” King explained. Still, it was – and remains – a radical concept to bring together, in prison, individuals from different racial groups to promote anti-hostilities. SF Bay View and Prison Focus was the basis of our curriculum.”

“I would give a youngster the paper and tell them to read a certain article, then to write about it and to bring it back to me a week letter. I had a bunch of the youth reading those papers,” King smiled, “then talking about it on the yard.”

In 2018 Min. King joined the No Joke Theater Group offered at CSP-LAC in Los Angeles County. Already an artisan of words, Min. King discovered a love of theater. Having embraced the power of music and art in changing minds, he quickly recognized the potential of contemporary theater to create unity and awareness, as well.

Thus after 18 years in the most notoriously violent prisons in the California prison system, including three consecutive years in solitary confinement, Min. King has finally returned home, with a wide array of experiences under his belt, a political and legal education, energy, courage and a blind determination to free his brothers and sisters, both inside and outside the prison walls.

Programming for Artivists Dec. 7 event

KAGE and event program coordinator Priscilla of Queen Memorial Church have coordinated the program for Dec. 7. Tiny of Poor Magazine, who also supported Min. King while imprisoned, will be the evening’s MC.

Min. King, Pyeface, is going to perform pieces written and previously performed alongside his peers in prison with No Joke Theater, including “A Chance” and “When the Panthers Died.” Poor Magazine will be performing a piece written and directed by Min. King, called “I Stand2Vote.”

The evening will end with a special feature of Min. King’s freshly recorded and not-yet released “San Quentin X,” a song and music video, written in honor of the San Quentin Six and Sitawa Nantambu Jamaa, and of all political prisoners. This song was written and produced to honor his comrades on the inside, and to raise funds for his comrades on the outside, still working hard to provide our locked up community members, the same life changing impetus that SF Bay View and Prison Focus inspired within Min. King.

Nube of California Prison Focus will be hosting Liberate the Caged Voices: “At this inside-outside community-led fundraising event, Liberate the Caged Voices – Free Sitawa! Campaign to support the Prisoners Human Rights Movement will continue its mission to elevate the voices of California’s prisoners, with a special presentation focusing on the Elder Sitawa Nantambu Jamaa, one of the leaders of the 2011 and 2013 Hunger Strikes, and other Elders in this movement through photos, letters and commentary.

Statements from the Elders will be read by their respective pen pals and others to honor the leadership and inspiration of Elder Sitawa, as they continue the struggle to gain their freedom and establish their existence through their transformational work inside and through a powerful collective effort for human rights in collaboration with the community out here.”

End note

While at 8 years old, King was treated as an adult when arrested and then placed inside an adult county jail, now at 46 years old, he is being treated like an 8 year old, monitored by an ankle bracelet and given an 11 p.m. curfew. Ankle bracelets, paid for by the “uncaged slave,” are extremely profitable for the industries that are scrambling to find new sources of income as the prison population diminishes and the Reentry Industrial Complex flourishes.

Min. King was not assigned an ankle bracelet for the first three months of his parole. He had acquired a well-paying job with benefits and remained focused on his art and giving back to his community. However, when Min. King offended an abrasive, verbally abusive parole officer by knowing his rights and not being afraid to say so, Min. King was arbitrarily assigned an ankle bracelet for three months. Luckily Min. King is staying true to himself, and will appeal this latest affront to his humanity.

For more information about Min. King X or to schedule a performance, visit www.prisons.org/speakers/37. Contact Kim Pollak, editor of Prison Focus, at kim@prisons.org.