by Joe Mangano

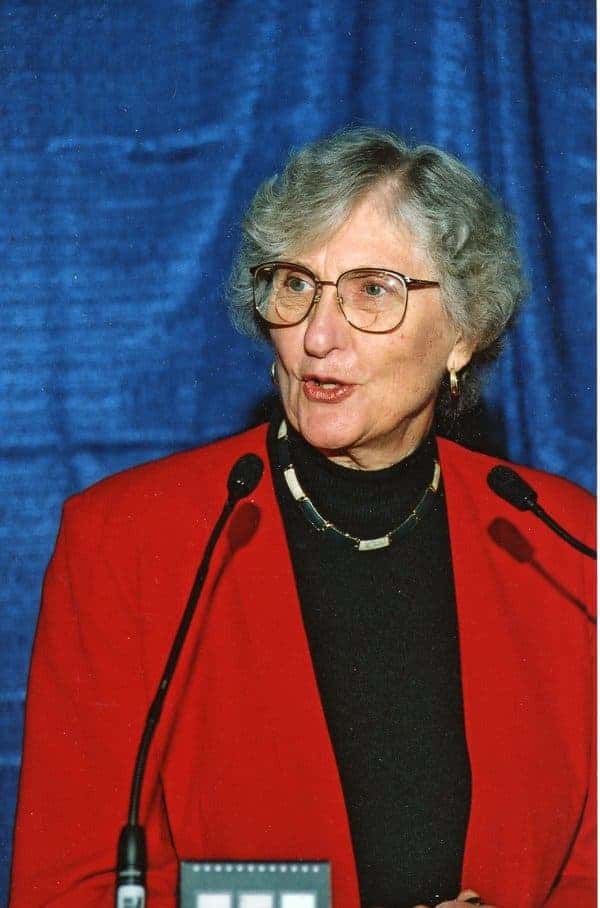

On Nov. 7, Dr. Janette Sherman passed away at 89. Janette was a frequent contributor to this publication – and indeed, she had much to contribute.

After college, she began a career as a scientist before going to medical school in Detroit in the early 1960s. Overcoming bias – she was one of very few women in her class – and the strain of raising two young children, she began an internal medical practice. It was here that she found her true calling: toxicology.

Janette wasn’t the typical doctor, running an assembly-line of “diagnose-and-treat” with one patient after the next. She wanted to know WHY people were suffering; causation was as important as medicine in her mind, something unusual for physicians.

She sensed an unexpectedly large number of her patients were suffering with diseases related to toxic chemical exposures, in the workplace and elsewhere. She shifted her priorities until toxicology was her full-time occupation. Her experience as an expert witness and consultant in over 5,000 workmen’s compensation cases may be a record.

She was recognized by other experts, when selected to be a consultant to the National Cancer Institute and Environmental Protection Agency. About 70 medical journal articles and two books later, her career would be considered complete for nearly anyone.

But in her late 60s, when many would slip into a quiet retirement, the ever-curious Janette was not done. She hooked on to the Radiation and Public Health Project (RPHP), a group of scientists and citizens concerned about nuclear power plants – especially the code of silence imposed against researchers from doing honest studies.

Any research published by experts that concluded radioactive emissions from nuclear plants were harming people would be slammed by the nuclear establishment in industry and government, risking a loss of grant funding for research and perhaps their entire job. But RPHP was self-funded and independent. Nothing other than name-calling could be done to group members, and truly objective studies began in earnest.

Relishing a good fight for the cause of humanity, Janette jumped in. Of the many studies she worked on, none was so powerful as the “Tooth Fairy Project” – not a children’s game, but a serious scientific study that collected 5,000 baby teeth and measured amounts of radioactive Strontium-90 in them – still the only study to examine the amount of radiation in bodies of Americans living near nuclear plants.

Not unexpectedly, levels were highest and rising fastest in children living closest to nuclear plants. More importantly, rises in Strontium-90 near reactors were followed several years later by rises in child cancer rates. Janette and her colleagues published six journal articles on results and received coverage by the New York Times, Washington Post, USA Today, CNN and other mainstream media – over the howls and protests of an angry nuclear establishment.

In her late 70s, Janette was asked by her fellow scientist Alexey Yablokov to edit a book on health casualties of the Chernobyl meltdown in 1986. Again, the nuclear establishment bent over backwards to minimize the number of those who were harmed. For years, they declared that 31 rescue workers who died quickly of acute radiation poisoning were the only victims of the disaster – ignoring the many anecdotes and reports coming from the former Soviet Union.

Working relentlessly for the next 14 months, she produced a professional English version of the book, which was published by the New York Academy of Sciences in 2009. The final calculations were that 985,000 persons had died from radiation exposures in the first 18 years after the meltdown, a number that will increase for at least seven generations. Increases in disease and death rates were found not just in cancer, but other diseases, and in virtually all organ systems – cardiovascular, neurological, digestive, urological, muscular, respiratory etc.

The angry reaction from the pro-nuclear side followed but didn’t faze Janette a bit. No pro-nuclear member dared meet with her or debate her. Among her many skills was her ability to communicate, not just to scientists but to the masses. For example, she would stand at the podium and hold up a lima bean. “This is a lima bean, which is the size of the average three-month-old fetus. Now raise your hand if you think a dose of radiation to this fetus is more harmful than the same dose to an adult.” Every hand in the room went up, and just seconds into her presentation, the point was made.

Life wasn’t all work for Janette. She had many interests; she was a great traveler, an avid swimmer into her 80s, a cellist (she started at age 56), and of course a mother and grandmother. She was a long-time friend of Ralph Nader, writing policy papers for him on health during his political campaigns, and was close with Helen Thomas, the legendary journalist who covered presidential news conferences for decades. But the planet and its people always came first.

The world, not just the current one but the future version, owes much to Janette’s brilliance, integrity and dedication to her fellow human beings.

Joseph Mangano, who works with the Radiation and Public Health Project, can be reached at odiejoe@aol.com. To learn more about Dr. Sherman in her own words, read “Radiation expert Dr. Janette Sherman: Less than one lifetime.”