by Ann Garrison

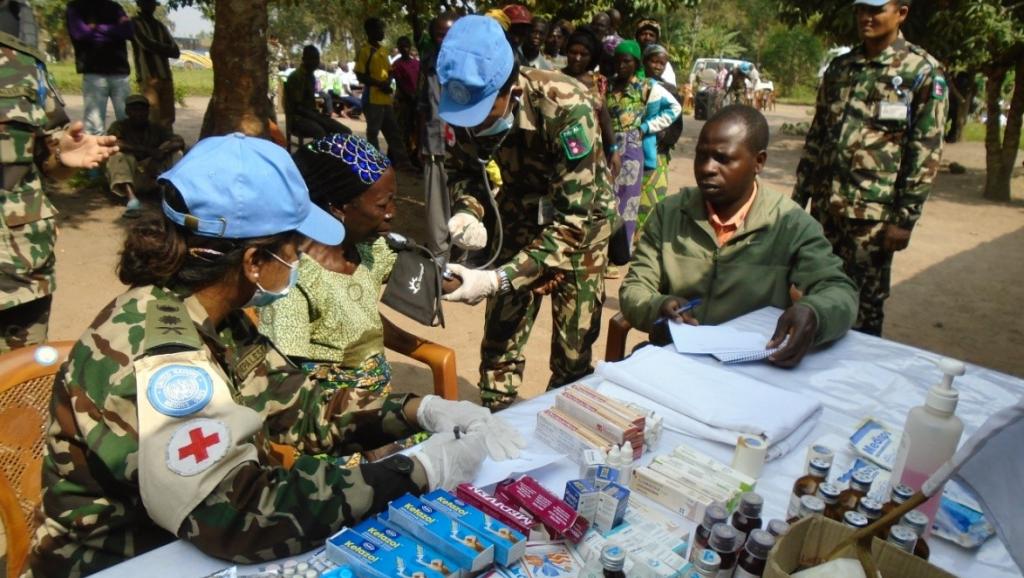

The UN has a long, storied history in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission (MONUSCO) was created by the UN Security Council nearly 20 years ago.

It is headquartered in Goma, the capital of North Kivu Province, which sits on the Congolese side of the Rwandan and Congolese border. It is primarily involved in the conflicts in the North and South Kivu Provinces and in Ituri Province.

North Kivu borders Rwanda and Uganda, South Kivu borders Rwanda and Burundi, and Ituri borders Uganda. Since 1996, the history of these provinces has been that of perpetual Rwandan and Ugandan invasion, occupation and resource plunder, and MONUSCO has failed to protect the people or the peace.

I spoke to Jean-Claude Maswana about why and whether anything can be done. Maswana is a Congolese native and economics professor at Ritsumeikan University, Japan.

ANN GARRISON: Jean-Claude, MONUSCO has 18,000 peacekeepers and a $1 billion annual budget. It’s been in DRC for 20 years, so it has to be one of the most spectacular failures in the history of UN peacekeeping.

JEAN-CLAUDE MASWANA: The UN troops in DRC are called “peacekeepers,” but there was no peace to keep in this part of DRC when they arrived nearly 20 years ago, and there’s been none since. MONUSCO’s real mission is managing the “silent violence” in which perpetrators cannot be readily identified, atrocities go unreported, and resources are smuggled out of DRC through Rwanda and Uganda. MONUSCO has been successful at securing the smooth supply of DRC minerals through the related global value chains.

Its failure to either restore or keep the peace has had tremendous benefits for DRC’s eastern neighbors and the gangsters who smuggle minerals through them.

At the same time, the relationship between MONUSCO and the DRC government has been outlandish. Numerous reports, some by the UN experts, document the role of Congolese officials and army insiders in the killings and resource trafficking, but MONUSCO still behaves as their faithful ally.

Many of these officials and army insiders are Rwandans pretending to be Congolese. So more and more Congolese are rebelling against MONUSCO’s presence.

AG: So much of the Congolese army, which is supposed to be protecting the people, prey on the people, and the UNSC ignores that or collaborates?

JCM: Absolutely. The Congolese army is full of Rwandan and Ugandan infiltrators, but mostly Rwandan. Nevertheless, most of the violence is now blamed on a Ugandan Muslim militia, the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), even though the ADF hasn’t been present in North Kivu for nearly a decade now. Their conflict was with Uganda, and the Ugandan army defeated them in 2008. Some were given amnesty to return to Uganda.

After UN investigators proved that the M23 militia was under Rwandan and Ugandan command in 2013, Rwandan President Paul Kagame, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, and their Congolese collaborator, then President Joseph Kabila, needed a new cover to hide their murder and plunder in eastern DRC. The defeated ADF was perfect, since it no longer exists, and everything was soon blamed on them.

AG: MONUSCO collaborates in this lie. Their force commander says their job is to help the Congolese army fight the ADF. So should the UNSC withdraw the peacekeepers and shut MONUSCO down, as some Congolese have demanded? There seems to be quite a bit of disagreement about this among Congolese.

JCM: It looks like most people disagree because the peacekeepers’ “withdrawal” hasn’t been clearly explained or defined. Some think the peacekeepers should leave now, ASAP. Others think they should remain but gradually withdraw.

My view is that they should announce a gradual withdrawal to be completed in two years, subject to some clear security benchmarks, including the arrest of well-known perpetrators by the ICC.

AG: Isn’t that the ICC of your dreams? One that would arrest Rwandan and Ugandan gangsters under Kagame and Museveni’s command and try them as such? The notorious warlord Bosco Ntaganda surrendered to the ICC in 2013, but then the court tried him as a Congolese, not a Rwandan, even though he’d spent his entire adult life under Kagame’s command. That made the court and the UNSC look as though they’d done something when in fact they’d once again obscured the nature of the conflict.

What would they do now? Try perpetrators as members of the ADF?

JCM: You’re absolutely right. The way the ICC conducted the trial of Bosco Ntaganda was disgusting, to say the least. At the same time, the government in Kinshasa never rejected that ICC posture of labelling Ntaganda as a Congolese.

Since the DRC government recognized Ntaganda as Congolese, the ICC might have had no other choice than to try him as such. The root of that absurdity is again on the side of what is known as the “DRC government.” Truth be told, the DRC government and its army are largely under the control of officials and officers who have also spent their lives under Kagame’s command.

Remember Kagame’s 2013 Al Jazeera interview when he clearly pointed out, beginning at minute 9, that “it is not those fighters of the Congolese CNDP [National Congress for the Defence of the People] only who have an association with Rwanda or the Rwandan military. Even those in the government were part of that precisely, right from the top. There is no single person in the DRC government with whom we do not have an association.”

This explains much of the DRC government’s silence on the killings in Kivu and the difficult posture that the ICC might have found itself in.

AG: Some have said they fear a sudden power vacuum if the peacekeepers leave. Is that the danger you’d hope to avoid with a gradual withdrawal over two years?

JCM: In part, yes. Nobody knows what might happen if MONUSCO leaves. Yet, the presence of MONUSCO is not making people feel safe either. Ultimately, a MONUSCO withdrawal is going to make the Congolese people responsible for their own long-run security. That will be a positive step.

AG: Others say that the UN mission has been such a disaster that it should be withdrawn as soon as possible and replaced by a regional force, perhaps one organized by the Southern African Development Community. What do you think of that?

JCM: I do not think MONUSCO should be replaced by another external force. Instead, the international community should help in cleaning up the infected and corrupted political system, which, as President Kagame confirmed in that Al Jazeera interview, serves outsiders, not the Congolese people. Once a transition plan is in place, free and fair elections with international monitoring can be organized, and the new government will take care of security. In short, there is no need to replace MONUSCO with another external military presence.

AG: An altogether different theory I’ve heard this week is that those protesting and demanding that the UN troops get out of DRC are in fact Rwandans who want them gone so they can take over. What do you think of that?

JCM: I have not seen any evidence to support that theory.

AG: OK, lastly, where can the political will to remove MONUSCO be found? When we talked in January 2018, you said that there’s an unspoken consensus among the powerful players for leaving the situation on the ground as it is because they all have resource deals with local players that are working for them.

The powerful players include all five permanent members of the UNSC – the US, UK, France, Russia and China – who have authorized and funded MONUSCO for 20 years. What could make them change their minds?

JCM: Only the Congolese people, their mobilization and determination, can force everyone to realize that the current situation is no longer acceptable.

AG: Withdrawing the peacekeepers obviously wouldn’t resolve the conflict in itself, so are you seeing this as a first step, or a step within some other process?

JCM: It is a first step that should be accompanied by other measures. Political transition is one. Justice is another.

Obviously, the so-called internal conflict in DRC is sustained by the perpetrators’ impunity. The 2010 “UN Mapping Reporton Human Rights Abuse in DRC, 1993-2003,” came out with specific recommendations that have huge potential for bringing perpetrators to justice and creating a strong deterrent for other potential perpetrators.

Before any withdrawal, the UN should make sure that MONUSCO ends its collaboration with the DRC government. This should include ending the coverup of the government’s 2017 murder of the UN’s own experts, Zaida Catalán and Michael Sharp in Kasai Province.

It should also include removing Rwandans from the Congolese army, which they have infiltrated for two decades now. So, a gradual withdrawal combined with the political transition and justice should restore peace and a normal life for ordinary Congolese.

AG: Is there anything else you’d like to say?

JCM: I’d like to remind readers that the DRC tragedy is a crisis of our collective and global humanity, not just a national conflict. We need more people to play a role, even if only by spreading the news and breaking the silence.

Too many countries and corporations are either supporting the perpetrators or striking deals with them for DRC minerals. This means that individuals and groups around the globe can act with regard to their respective governments and/or corporations.

Ann Garrison is an independent journalist based in the San Francisco Bay Area. In 2014, she received the Victoire Ingabire Umuhoza Democracy and Peace Prize for her reporting on conflict in the African Great Lakes region. Please support her work on Patreon. She can be reached at ann@anngarrison.com.

Dr. Jean-Claude Maswana is a Congolese native and activist, and an economics professor at Ritsumeikan University in Japan. He can be reached at jclaumas@yahoo.com.