by Jason Renard Walker, NABPP Minister of Labor

Maggie Ray Anderson, a senior studying law and justice in Washington state, hopes to one day involve herself in the criminal justice reform field. Unlike many newly arriving activists, Maggie’s interest is helping convicted sex offenders rehabilitate through effective positive programming and counselling. “I’m hoping to make changes,” she says.

Despite the negative that is placed on most sex offenders, Maggie is more than willing to take on the challenge. With a very versatile appetite for change, becoming a lawyer, overhauling America’s prison system and collective struggle with prisoners is all on her plate as alternate offshoots to Plan A.

For her ethics class, she wrote a brilliant paper titled “Prison Labor, Race, and Ethical Dilemmas,” which explores and criticizes the perils of prison labor and its exploitative dimensions. This paper was published as an introduction in my upcoming ebook, “Reports from Within the Belly of the Beast: Torture and Injustice inside Texas Department of Criminal Justice.”

One of her first steps, she says, in working toward her goal is creating a podcast that gives prisoners and their families another platform to share their voice, reconnect with their communities, and present ideas and solutions. But first, she’s preparing for her graduation from college.

Maggie is by no means the only college student who can change the prison reform paradigm. Students at Colorado College have stepped up to the plate. With their “Colorado College Prison Project,” student activists Katie Lawrie, Theresa Westphal and Emma Kerr have taken the initiative to provide support to incarcerated activists. From legal defense fundraising to protesting, the Colorado College Prison Project not only wants to protest for real change, but to physically involve themselves with the prisoners who are proactive in achieving this end.

Activism in the age of prisoner resistance has called for a revolution in how prisoner rights organizations are involving themselves with prisoners. The Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee (IWOC) is a prime example of this prison reform paradigm shift.

The IWOC is a branch of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). The IWW understood and analyzed the in-prison civil rights struggles and saw these struggles as being tied into the struggles of the working class. It saw that these small time movements were gaining some positive currency, an incentive for creating the IWOC, which gives prisoners the opportunity to advance their own labor unions, strikes etc. with the exclusive help and support of the IWW. Many state prison systems have banned such activity with the help of federal courts; while a few others allow it with very strict guidelines.

The Attica Prison Rebellion serves as a hallmark example of the lengths prisoners will go through to be treated humanely and the lengths guards and the state will go through to keep their punishment programs secret. For a full scope on the Attica Prison Rebellion, see Heather Ann Thompson’s “Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy.”

Even though prison reform has been a key topic in today’s political campaigns, and celebrities like Kim Kardashian, Jay-Z and Meek Mill have initiated their own fledgling advocacy groups, there will still have to be an element in existence that merges these thoughts, ideas and trends with practices that will spearhead legislative change for the long run. One key example of this is the support and solidarity that protesting concerned citizens provided to prisoners during the 2016 and 2018 national prison work stoppages. Bad prison conditions still exist throughout the country, but such unity provided a buffer for insurance towards any in-prison movements that may come in the future.

Activism in the age of prisoner resistance has called for a revolution in how prisoner rights organizations are involving themselves with prisoners.

Amani Sawari is an extremely gifted young college graduate-turned-activist who not only supports prison reform and real change, but has brought forth various writing platforms and program opportunities designed to soften the outer shell that has made real change difficult. She is a writer, founder of Sawarimi, spokesperson for Jailhouse Lawyers Speak, and national co-ordinator of their Right2Vote campaign with the support of the Roddenberry Foundation. She has a periodical, free to prisoners, called Right2Vote Report, which details the on-going efforts to give prisoners their right to vote back. She also has a section in this periodical and on her website that gives prisoners a chance to voice their opinions and ideas via artwork, essays and poems.

Her efforts often take her from one side of the country to the next, partnering with organizations such as Prisoner Legal Action Network (PLAN), Pink Peacock Project and Triple-P Radio, a place that gives lifers (those with life sentences) a platform to express themselves. A lot of these organizations and advocates she works with aren’t familiar to the broader audiences in America, so anyone who’s interested in learning more can contact Amani Sawari via her website, www.sawarimi.org. If you are an activist working alone or are looking for involvement, Amani is there for you.

Prison reform and positive change is a lot deeper than legislators passing umbrella bills that target a specific class of prisoners or ex-cons. Given that the release plans and parole eligibility requirements vary from state to state, the Maggies, Kates and Amanis approaching from a different angle and empathetic perspective of the prisoner is a decisive factor in not only how far prisoner advocacy will go, but how fast change will come as a result.

Many prisoner rights activists are unaware of each others’ existence, even though they share similar goals; but with the rise of advanced technology, this is slowly changing, thanks to social media outlets like Facebook, Twitter and the like. During the civil rights era in the 1960s, the Martin Luther Kings didn’t have this luxury and had to actually walk the grounds they sought to change, which often proved to be fatal, and made such individuals targets of police dog attacks, firehosing, verbal ridicule by unruly citizens and more. This in itself discouraged white sympathizers and those advanced in age and physically unfit from taking to the streets.

Now, these same individuals can play a pivotal role from their home and with their smartphones and computers – while those suited to walk the changing grounds do just that. Others, unconcerned, simply ignore the whole debacle, posing as ignorant. “I think many people have the privilege of pretending these problems don’t exist, or they haven’t even encountered information about what it’s really like in the first place”, Theresa Westphal explained to me in a letter.

These same individuals she’s referring to are mainly rightwingers who are affected by availability bias and refuse to educate themselves beyond the information provided by outlets like Fox News, who see prisoners as subhumans who are getting what they deserve – case closed.

On the other side of the fence, there are a wealth of people who not only want to know the truth about prison conditions, but provide whatever support they can to right the wrong. Azzurra Crispino is one of many people who reflect this type. When she isn’t being a professor of philosophy at Austin’s community college, she’s networking the PAPS blog (Prisoner Assistance Prisoner Solidarity), uploading essays from prisoners across the U.S. onto this blog, writing them letters of support, speaking with them on the phone, serving as a media correspondent for hunger strikers, work strikers etc. and, most importantly, keeping their spirits high. Her focus isn’t on popularity, she says, but using her own time and platform to penetrate the shell that’s blocking prison reform and real change from becoming a reality.

Unlike most government-created reform groups, these groups mentioned here aren’t profiting, monetary-wise, and often have to conduct fundraisers just to have the means to keep the thousands of prisoners they support in the loop, e.g. sending them newsletters, legal documents, letters etc. This, basically, is because they are engaged in advocacy work independent of government assistance and pursue the agenda to do more meaningful and practical things than what the government has ever done for prisoners.

But that isn’t to say that the tools provided by the government aren’t useful. Effective, yet costly, devices sold by the profiteer behemoth JPay give some state prisoners access to legal and educational programs. At a medium cost of $70, prisoners or their families can buy this device that can be used for a variety of things, including playing video games, listening to music, sending and receiving emails and more. Yet, this equipment is only sold in select state prisons, Texas not being one of them. County jails like Tarrant County seem to be a pioneer for them to hit the Texas prison system.

It is well-known that there is a prison problem in the U.S. The U.S. locks up more people per capita than anywhere else on earth, housing some 2.3 million prisoners in 102 federal prisons, 1,719 state prisons, 942 juvenile correctional centers, a resounding number of city and county jails, immigration detention centers and pre-parole release centers.

As the world becomes dependent on digital and computer skills and learning at pace with technology, conventional thinking around prison reform and education isn’t working. That’s why it’s imperative that more forward-thinking advocates and legislators do what needs to be done to bring prisoners to par with an ever-growing and changing society, regardless whether it requires that they can’t save face for their counterparts working against progressive prison reform.

Under federal law, prisoners don’t have a right to access computers, regardless of whether they lack internet access. Data that was obtained by London-based writer Christen Ro in 2015 shows that only 22 percent of Americans in prison have ever used a computer. This suggests that those who will eventually re-enter society will do so lacking the basic computing skills needed to hold a decent-paying job and, in many cases, without a GED, trade or other skill that will give them an advantage over other potential employees seeking the same job position, but with something to certify their worth.

Despite their high cost, the JPay mini-tablet and a prisoner’s right to access it is a step in the right direction, as those lacking a GED or having trouble with speaking English can use them while incarcerated, which ultimately helps them upon their release. Those who already have a GED can take college coursework, watch vocational videos and do so at any pace and skill level they can grasp. The only downfall I see heading in this direction is that prisoners and/or their families are only contributing to the high-fees model that has made JPay and its counterparts a profitable enterprise.

[T]he U.S. prison system is an overtly for-profit industry, which ignores the connection between the exploitation of prisoners for profit and high recidivism rates

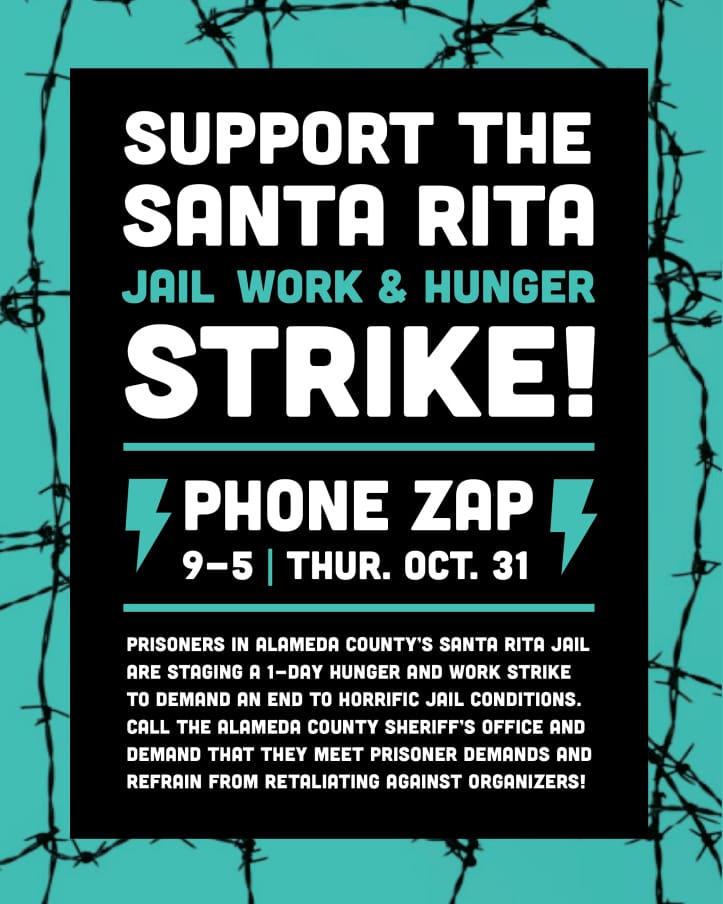

Other prison profiteer companies like the Keefe Group, Securus Technologies and Access Securepak are all JPay-like-minded, contracting with prison systems all across America, who then sell their commissary service and telephone service to prisoners at exorbitant prices. In California’s Santa Rita county jail, a pack of Top Ramen noodles that can be bought at 10 packs for $1 on the outside, costs the detainees 90 cents a pack.

Then in Texas, one 15-minute phone call used to cost prisoners $3.60 with the commissary vendor who sold the minutes imposing their own personal tax. But, following the 2018 national prison work stoppage, the cost was reduced to 6 cents per minute, with the time allowed per call rising to 30 minutes. The commissary vendor-imposed tax was removed but is now taken by the phone company, who could possibly split the annual gross with the commissary vendors. So, basically, a prisoner who buys $50 worth of minutes will only have around $47 placed on his phone account, without any explanation as to where the money went, as there is no mention of the tax listed on the commissary purchase receipt or explained to the prisoner when they place a call.

Several steps are needed. First, an overhaul of the prison system will also call for the overhaul of the companies that contract with the prisons, mainly to exploit the absence of options a prisoner has by selling items for 10 times more than what they would cost a non-incarcerated individual. Either the prisoner buys from them, or has nothing at all. Also, these companies have a financial stake in incarceration, which contradicts any attempt to reduce prison populations.

Second, the U.S. prison system is an overtly for-profit industry, which ignores the connection between the exploitation of prisoners for profit and high recidivism rates. Supposedly designed to “correct” the incarcerated, the complete opposite occurs, as prisoners learn that disadvantaged people are also a very profitable commodity. One of the founders of JPay Inc. was an incarcerated man, who used his experience to exploit this paradox. And prisoners who can afford to buy commissary items in bulk can re-sell these items on the prison markets for twice the amount they were purchased for. Now you have some prisoners who have limited funds, using this black market to take care of their basic needs, as they can borrow right then, as long as they pay interest later. Given that prison systems in the state of Arkansas, Georgia, Texas and Alabama work prisoners for free, their only option of paying back what they borrowed is through family and friends.

States that do pay prisoners to work often pay them wages as low as 6 cents an hour. So a prisoner who gets paid this low wouldn’t even be able to buy a pack of Ramen noodles after an eight-hour work day if he was incarcerated in California. And those working in California get paid less than 40 cents an hour, unless they’re helping fight fires, in which case they get $1 a day, but aren’t allowed to pursue the job upon their release because of their felony conviction. Another example of the penal system profiting off of prisoners, without providing them job skills they can use upon their release.

This is why it is important to not only support the activists who seek real change, but to get involved yourself.

Most Americans see prison reform as a mechanism that can only be advanced by so-called professionals that are, one way or another, employed by the government. But, in reality, prison reform starts with the taxpayers and loved ones of those incarcerated. They are the ones who elect state and judicial representatives, who have the most influence on policy changes and their implementation. As for the prisoner, his or her influence is limited to bringing awareness, organizing protests and petitions and so forth. So, in the event a policy or custom is affecting the rehabilitation of prisoners in a particular state, the representatives will overlook it until those who have the most influence on their job stability use it to threaten that stability.

In-prison channels for change are extremely limited to the prisoner, and often allow only the filing of civil rights lawsuits. When going this route, the prisoner is up against the state attorney general’s office, who has unlimited resources and legal expertise, and whose interest is in protecting the sued entities and helping them to get absolved of committing any wrongdoing, even when it’s obvious that they have.

Under circumstances like this, a prisoner’s suit is almost always dismissed because of the prisoner’s lack of resources and legal knowledge and because they are a prisoner. Courts are reluctant to apply the same legal bias given to attorneys, and they often see the unfortunate mishaps prisoners are prone to face as the daily goings-on of prison life and the penalty they pay for going to prison.

Despite this, there are activists willing to give their time and resources to the serious litigator. Even though the litigation process can take many years, a suit that challenges a policy or practice and prevails makes the working ground firmer for activists, in prison or out.

Dr. John S. Dolley, who serves as a hub for litigators, activists and organizers in prison, has done his fair share for years. He’s a key factor in helping those unknowledgeable in filing Habeas Corpus writs to do so, those litigating to get relevant case law, organizers who need copies of fliers and petitions to get them, and a host of other ground work. Given that the Texas prison system is one of the worst, conditions-wise, his presence in this state has played a key role in several policy changes, including prisoners’ religious rights and right to not suffer extreme heat conditions.

Other organizations that assist prisoners, like the American Civil Liberties Union, are only willing to assist a handful of prisoners according to the amount of media attention the violation receives and whether the violation affects a large class of prisoners. The Human Rights Defense Center (HDRC), which publishes Prison Legal News, has been effective but only in a limited number of cases. This makes Dolley’s role in activism in the age of prisoner resistance critical and worthy of receiving a broader range of volunteers and activists in Texas. Texas does have the biggest prison population and the largest number of prisons in the country.

There are also food vendors and medical assistance contractors that have exploitative tentacles, such as Corizon Healthcare (formely Corrections Medical Services) and Aramark foods. The legal kickbacks they provide to the prisons that contract with them make it nearly impossible for them to cease to exist, even when the health care and food service is constantly paying out millions of dollars a year for lawsuits involving the deaths and mistreatment of prisoners under their care.

As long as prisons are allowed to contract with such entities, which have low standards, reforming any aspect of the penal system within the grasp of their tentacles will continue to prove impractical. As a ripple effect, the wealth these companies pull in will allow them to merge with other smaller companies for the purpose of withstanding the blow of reform, while regrouping and exploiting another defenseless area. Like the misconception that changing a company’s name changes their practices and exploitative nature. CoreCivic, formerly the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA), is a prime example of this vile masquerade.

Not only was Corizon sued over 1,300 times in the last seven years, according to the Guardian, for cases often including wrongful deaths, this same report suggests that some of the suits were against doctors and nurses for sexual misconduct, “including a female employee who paid inmates for sex.” Many of these cases were reported in Prison Legal News. (See PLN, September 2017, page 32, and March 2014, page 1.)

Then there is Aramark, a multi-billion-dollar food vendor based in Indiana, whose mission is to keep expenditures as cheap as possible, while devising ways to sell low-quality goods at exorbitant prices. Its contracting extends to sports franchises as well. But in the context of the former, its recipients are prisoners.

It has been reported that Aramark pulled in a whopping $14 billion in the 2018 fiscal year alone. It is no wonder why this company was ranked by Fortune 500 as the 27th largest employer, and made the Forbes list that includes regulars like Google, Facebook, Amazon and other major capitalist corporate profiteers.

Regardless of Aramark’s shameful history of serving rat- and maggot-infested foods in Michigan’s prisons, according to a 2015 report from the Detroit Free Press, it is still a well-sought-after food vendor by most of the state prisons in the U.S. That is mainly because prison systems are now trying to cut costs by privatizing most of their food service custodial functions in particular. Texas is the exception to the rule because its system raises its own cattle, chickens, pigs, veggies etc. at the cost and expense of unpaid prison labor.

From published articles and accounts of prisoners that have to eat Aramark food, every account says that the food not only tastes bad and is served in paltry amounts; the foods they are supposed to mimic don’t share the same taste and nutritional value, namely soy meat “gas patties” as they are called in the Lubbock county jail because of their ability to wreak havoc on one’s digestive tract. Often leaving a cellblock full of prisoners passing gas all day long. Or, at worst, have some experiencing some very painful, dry defecations.

As long as behemoths like this exist and give prison systems a cop-out to save and make super-profits, this aspect in need of reform will go completely unscathed. It shouldn’t be acceptable for those who profit from the penal system to be the same entities that pick and choose which areas need reforming and which ones are perfectly fine. There will be little if any discussions about the budget increases that would be needed to boost the food service, medical care, labor wages, privileges and what not to a decent level. In fact, these areas are the first hit when a prison system needs to cut its budget in order to accommodate guards and staff with things that serve no penological objective or further a governmental interest.

This is why it is important to not only support the activists who seek real change, but to get involved yourself.

Here in Texas, part of a recent budget cut provided the warden’s offices throughout the state with leather chairs and upgraded air conditioning units, despite their refusal to do the same for prisoners that are forced to live in housing areas that become hotboxes in the summer because they lack any air conditioning.

With the passing of the landmark criminal justice reform measure, the First Step Act, that was signed in December 2018 by President Donald Trump, over 3,000 prisoners in federal prisons were released and 1,691 more federal prisoners saw their sentences reduced, according to the U.S. Sentencing Commission (USSC). As of now, this reform measure applies to federal prisoners who meet the criteria, and it isn’t clear when, or if, this program will be available to state prisoners, and if so which ones. While it’s good that something has gone into effect that gives prisoners an early out, it still needs to be reformed if these same individuals are faced with the same problems that brought them to prison in the first place – and if they don’t have access to modern-day technology while they are imprisoned.

One positive about the First Step Act is that it removed mandatory life sentences for “three-strikes” drug offenders in exchange for 25-year sentences, and it gave judges a broader range of options to use a “safety valve” provision when sentencing nonviolent drug offenders.

This simply implies that a judge has authority to reconfigure the maximum term a person is sentenced to, if they choose to plead guilty and rely on the guideline. Before, judges had a window sentence, e.g., five years to life, with which to impose punishment. Now they can change this according to behavior, role in the crime etc. This also takes pressure off of those facing long sentences and who would otherwise be tempted to inform on their co-defendants to get a lower sentence under 5k1 sentencing guidelines.

But in any event, outside of government control and influence, citizens across the country are doing what they can to speed up the process and expose any flaws in bills that claim to be reform measures.

Stay-at-home moms, blue collar workers and many others are being drawn into activism, and not as money-making opportunities. Thirty-eight-year-old Cassandra Gatelein started an advocacy group called Cape May County Indivisible, following and in response to the “surprise” election of President Trump. Their current focus is on justice. “We fight against the Trump administration and organize for social, racial, reproductive and environmental justice. I’m very liberal/progressive in my politics. I am definitely interested in prisoners’ rights and would like to do more work on those issues,” says Cassandra, who’s known as Sandy by her friends and family.

As of today, Sandy is working as a tattoo apprentice in an all-female tattoo shop. Before this stroke of luck, she was doing full-time tarot readings, which she still does part-time, as well as working on a few psychic hotlines.

During the winter in her hometown of South Jersey, Sandy says that it’s cold, quiet and empty; but in the summer the nearby beach and boardwalk is teeming with tourists.

Any of you who may happen to be vacationing in South Jersey this summer and run into Sandy, don’t be surprised if you find yourself involved in activism and prison reform. As Maggie, Katie, Theresa, Emma, Amani and so many others are showing, a want and need to assist in positive change is contagious. Even a psychic couldn’t have seen it coming.

Dare to struggle, dare to win! All power to the people!

Notes for further reading:

- christinero.com

- prisonlegalnews.com

- jasonsprisonjournal.com

- https://howwegettonext.com/without-technology-inside-how-can-prisoners-thrive-when-they-get-out-8ba7ffbf098

Send our brother some love and light: Jason Renard Walker, 1532092, McConnell Unit, 3001 South Emily Drive, Beeville, TX 78102.