by Bill Nichols

Jason Goudlock, an Ohio inmate, expected to gain his freedom soon when he wrote to me in 2008. He had served 14 years, beginning when he was 18, and he wanted to learn how to make a documentary film about the challenges he expected to face when he was released from prison. Unfortunately, he didn’t need to worry about adjusting to life on the outside anytime soon.

Still imprisoned today, Goudlock received a five-year “flop” in August – a parole board decision to hold him at least until 2024. That’s the bad news.

Since 2008, Goudlock has worked with me on his writing. He’s published a novel, “Brother of the Struggle” (2014), as well as many essays that can be found at www.FreeJasonGoudlock.org.

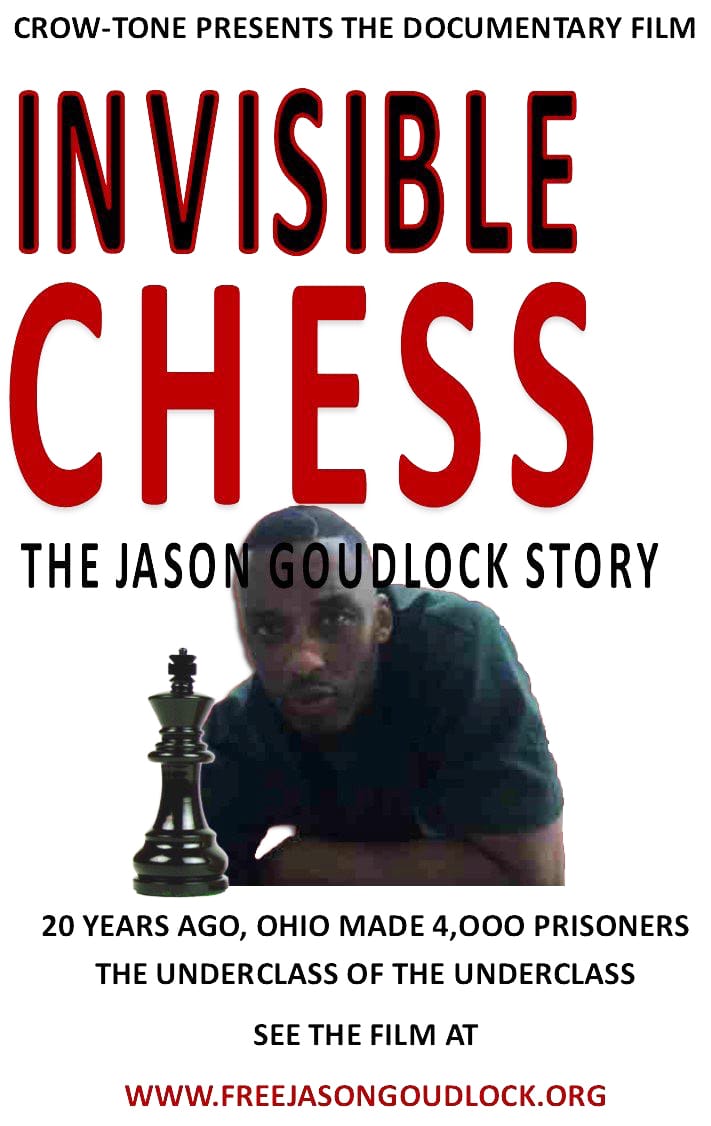

And I found Samuel Crow, a documentary filmmaker interested in prison reform. Crow recently completed work on “Invisible Chess: The Jason Goudlock Story,” a documentary now available free at www.FreeJasonGoudlock.org. (For a trailer, teacher’s guide, press kit and more see www.InvisibleChess.com.) That’s the good news.

Instead of focusing on the challenges Goudlock will face when he is finally free, “Invisible Chess” explores the injustice Goudlock and many other Ohio inmates face now. A “truth in sentencing” law Ohio passed in 1996 created a growing class of “new-law” prisoners who know exactly when they will get out.

“Old-law” inmates like Goudlock, who went into prison before 1996, are made vulnerable by this discrepancy. They can be denied parole for fighting even when they are simply defending themselves from younger men who will never face a parole board. The truth is “old-law” prisoners keep the Ohio Parole Board in business. And Goudlock has been denied parole six times.

When he first contacted me, he’d just read an essay of mine, “Contemplating Torture,” in which I compared our country’s use of isolation in prisons with our use of torture in Iraq’s Abu Ghraib prison. At the time Goudlock was in the Ohio State Penitentiary (OSP), a high maximum-security prison (“supermax”) where most of the men are held in isolation.

At the age of 12, Goudlock was sent away from his home in Cleveland for almost three years to a private residential treatment center in Pennsylvania, where, he writes: “I spent about two-thirds of my time in isolation.” Later, in our correspondence, Goudlock seldom mentioned his isolation at OSP, but in the next few years he would complicate my understanding of its effects.

Goudlock, 44, has experienced isolation off and on for most of his life. In recent years he has reluctantly begun to embrace it despite advice like this from attorney Alice Lynd, probably the wisest of his many correspondents:

“People need to be interacting with other people in order to maintain their perspective. Reading is fine, but not to the exclusion of living interaction with other people. You could be so messed up by the time you were released from prison that it would be very hard to adjust.”

I’ve mentioned such dangers to Goudlock too, adding that the Parole Board uses his unwillingness to live in the general population as evidence that he’s not ready to be released. This is his answer:

“If I call attention to corruption in the criminal justice system, as I have, my time will be increased, as it has. I have come to believe the only way I can survive my time in prison is if I’m isolated from the general population. …

“Trying to study and write in a general population cell makes as much sense as a student trying to study for an exam at a heavy-metal concert instead of in a library. Solitary confinement is no library, but it is the lesser of two evils. It is a stressful, often depressing, environment, but I’d rather be stressed and depressed and able to function than unable to function at all.”

When prisons are run unjustly, Goudlock has convinced me, a prisoner who is strong enough psychologically can sometimes find a better life in the “hole” than in the general population. Ohio has such a prison system.

There is irony in my relationship with Jason Goudlock. He got in touch with me because of that essay I wrote calling our nation’s use of isolation torture. While he hasn’t convinced me otherwise, he’s shown me that an injustice like the old-law/new-law discrepancy can make isolation preferable to life in the general population for some prisoners.

Another irony: making “Invisible Chess: The Jason Goudlock Story,” Samuel Crow and I uncovered evidence that Ohio’s “truth in sentencing” legislation reduces the chance that “new-law” prisoners will participate in classes and other activities that encourage rehabilitation.

One more irony: a condemned man mentored Goudlock while he was in isolation at OSP. Siddique Abdullah Hasan, an African-American imam, was sentenced to death for his role in a 1993 prison uprising at the Southern Ohio Correctional Facility in Lucasville, Ohio, that led to the deaths of nine inmates and one guard. Hasan played a crucial role in negotiating an end to the uprising, and in a trial that followed the rebellion some inmates were given shortened sentences after testifying against him. (See Staughton Lynd, “The Untold Story of a Prison Uprising,” 2011.)

Goudlock talked with Hasan when he exercised in a day room outside Goudlock’s cell. He read some of Hasan’s essays. He began to write after months of little more than shouting protests in his cell about his unjust predicament.

He wrote “Brother of the Struggle” and his many essays. He can be found commenting on the American flag, hip-hop and “Invisible Chess” on www.prisonradio.org. He has become a crusader against Ohio’s unjust sentencing guidelines and is likely to continue even if it means another “flop” and more time behind bars.

Anyone wanting to urge the Ohio Legislature to resolve the unjust discrepancy in the state’s sentencing guidelines can contact Sen. Cecil Thomas, Senate Building, 1 Capitol Square, 2nd Floor, Columbus, OH 43215, 614-466-5980, and Gov. Mike DeWine, Riffe Center, 30th Floor, 77 South High St., Columbus, OH 43215, 614-644-4357.

Bill Nichols, a retired English professor, writes columns for the Valley News in New Hampshire. He can be reached at nichols@denison.edu.