by Diana Hembree

If you experienced severe hardship as a child, are you more likely to have children with behavior or mental health problems?

The short answer is yes.

A recent UCLA study shows that the children of parents with four or more Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), such as abuse or neglect, are twice as likely to develop ADHD, which makes it more likely children will become hyperactive and unable to pay attention or control their impulses.

In addition, their children are four times as likely to have mental health problems such as depression and anxiety.

The key phrase is “more likely” – that is, it’s not inevitable. Even if you have multiple ACEs, your children will not necessarily have behavioral health problems. A positive parenting style can help protect children against this risk, according to researchers.

Replacing ACEs with ‘PCEs’

Adults who report more positive childhood experiences (PCEs) are less likely to suffer from depression or poor mental health – and are more likely to have healthy relationships, according to a recent study from Johns Hopkins University. The seven early experiences that researchers found made the difference were being able to:

“1) Talk with family members about their feelings; 2) Feel that their families stood by them during difficult times; 3) Enjoy participating in community traditions; 4) Feel a sense of belonging in high school; 5) Feel supported by friends; 6) Have at least two non-parent adults who take genuine interest in them; and 7) Feel safe and protected by an adult in their home.”

Other studies have found that childhood play, sports, spending time in nature, and even doing chores help protect against the impact of early adversity. “One of the worst things to do to kids with ACEs is to treat them like damaged goods,” Tufts University researcher and pediatrician Bob Sege has said. “Doing chores can help them develop a sense of competence and self-worth.”

When a child cries

Some parents are good at talking with their children and giving them support, but find crying scary and even triggering. They may even feel frustrated and angry.

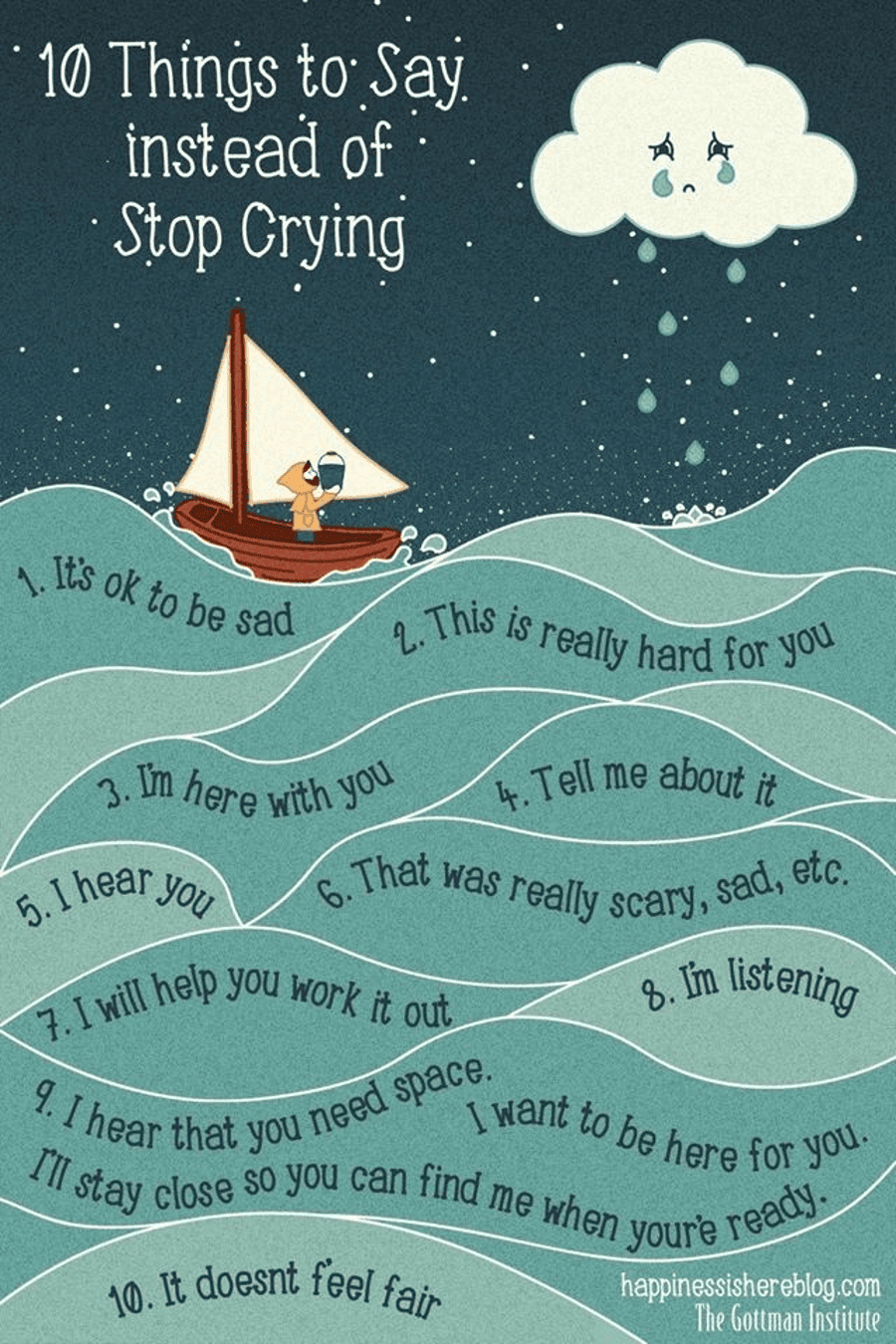

The Gottman Institute, which has a long history of research into relationships, has suggestions of what you might say to a child instead of “stop crying”:

Spare the rod

Another area where you may want to change the playbook is discipline. Kids need – and want – firm limits, but it’s good to use positive discipline such as a cool-down time and talk or natural consequences. Experts advise avoiding physical punishment such as slapping, belting, switching or spanking. This can lead to trauma in a child without ACEs or exacerbate trauma in a child with one or more ACEs.

Now, this is a sensitive issue for many parents. One reason is because this may seem like a rebuke to their beloved parents, especially if their parents favored physical punishment. How often have you heard someone say, ‘Well, my parents gave me a good old-fashioned whipping whenever I needed it, and I turned out great!’

Well, often parents are worried sick and use corporal punishment to try to deter their children from getting in trouble – or even killed – in a world that can be risky and dangerous, especially for African American boys. But deciding not to hit your child doesn’t mean you love your parents any less. They did the best they could; it’s just that we know a lot more now that we used to about what can harm or traumatize our children.

“If I had known better, I never would have hit your brother,” my father told me decades later. “. . . I wish to god I could go back and do it all over.”

The American Academy of Pediatrics and dozens of other health, medical and children’s organizations all advise against punishing kids by hitting or even spanking them. There’s lots of research into the mental and physical trauma from physical punishment, including one study into the “belt theory of juvenile delinquency.” The researcher found that belting a child encouraged obedience during childhood, but in adolescence, that punishment no longer worked; in fact, the child was far more likely to get in trouble and enter the juvenile detention system.

As an aside, this was certainly true in my own family. My father – one of the world’s most wonderful men, as far as my brother and I are concerned – nonetheless felt compelled to belt my brother for acting out in class (not realizing he had bipolar disorder).

Just as the study predicted, when my brother became a teenager, this ceased to have an effect and he got into all kinds of trouble, running away and nearly ending up in juvenile hall. “If I had known better, I never would have hit your brother,” my father told me decades later. “And honey, I want you to write this down and use my real name. It was wrong, and I’m sorry. I wish to god I could go back and do it all over.”

Breaking the cycle

Here is some other counsel from experts on how to break the cycle of intergenerational trauma:

– Take a deep breath when you’re stressed out. Breathing in and slowly exhaling to the count of four interrupts the stress response. Repeat as necessary.

– Build in some daily rituals. Scientists say that routines and rituals are critical for healthy child development. Cook and eat together (a warm atmosphere is more important than the meal itself), watch Sesame Street or the Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood with your preschooler, and read to your kids at bedtime. Even sorting clothes together while catching up – all these “anchoring” rituals can help create closer, more loving relationships with your children, according to Dr. Barbara Greenberg, a clinical teen psychologist licensed in Connecticut and New York.

– Take care of yourself. Take a walk with a friend, watch the dancing cockatoo on YouTube, have the neighbors over for a picnic. Feeling happy will help you stay calm and nurturing with your children.

– Consider a peer parenting coach. “We found this really promising,” said UCLA study leader Adam Schickedanz, MD. “When it’s someone from your community or social network, it’s much easier to trust them.” Ask your health provider about parenting resources in your area.

– Take a parenting class. “It’s important to realize that when it comes to parenting, not one size fits all,” says Greenberg. “If the class doesn’t feel right to you, try a different one.”

– Get more support. If you’re depressed or at your wit’s end, consider seeing a mental health professional for help.

References

Schickedanz A, Halfon N, Sastry N, et al. Parents’ Adverse Childhood Experiences and Their Children’s Behavioral Health Problems. Pediatrics. 2018;142(2)

Hembree, D. Don’t Know Why Your Kid Has Behavioral Problems? Your Own Childhood May Hold Clues. Medium.com. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@dkhembree/dont-know-why-your-kid-has-behavioral-problems-your-own-childhood-may-hold-clues-8a2e62991396?source=friends_link&sk=ddd810f3b1795d8568a403c18eba6784

Diana Hembree is a science writer for the Center for Youth Wellness. She is an award-winning journalist who has worked at Time Inc., the Center for Investigative Reporting and the Energy Bioscience Institute and has written or edited for Forbes, HealthDay, the Washington Post, PBS Frontline, Vibe and many other places. She can be reached at stresshealthnow@centerforyouthwellness.org.