Without emergency changes to foster care law during the COVID-19 crisis, parents stand to lose their kids.

Mental health professionals diagnosed me with varying degrees of the same ailments: situational depression, adjustment disorder, PTSD – all resulting from the removal of my son from my custody. In truth, I had plunged deep into an endless well and struggled each moment to simply move forward. I had lost the one thing in this world that ever truly meant anything to me. I was devastated.

There is nothing more sobering than waking up one day utterly powerless to the child protection case that has seized control of your life. Child abuser. Drug addict. Loser. Everyone around you is so quick to judge without stopping to consider the circumstances. The stigma is what keeps most in hiding, what keeps most of us from speaking out and fighting back against the senseless injustices.

During the time that my son spent in foster care, arriving at each visit during this period of depression was like coming upon a waterfall in the desert. Each and every minute of those visits was glorious; they were the light in the midst of pure darkness.

For my son, those visits were both brilliant and awful. Brilliant because he cherished each moment. Awful because at the end of each visit he could never come home with me.

We had our visits out in the community, which I know now to be an unusual luxury. We visited at the California Academy of Sciences, the Exploratorium, Six Flags and Golden Gate Park. I went to great lengths to ensure that each and every visit was an experience, to ensure there would be no “missed opportunities.” I was aware, also, at these supervised visits, that there was always someone watching me, taking notes, judging my fitness as a mother.

My son and I were eventually reunited, but it was an uphill battle that lasted far longer than it should have, and it had a lasting impact. For many, many months after his return, he woke up in the night screaming. He had recurring nightmares that everything around him was crumbling, that he’d awakened and everything was gone: his toys, his bed, me.

Now, years later, he talks about his time in foster care with such insight. He speaks about how it felt to him that he had nothing, how he wasn’t loved, and how he was always hungry in his stomach and in his heart.

My case was contentious and I came dangerously close to losing my son forever. It was the visits that saved us. Having regular, sustained, meaningful visitation allowed us to maintain our bond and gave us the opportunity to show that it was in my son’s best interest to be reunified with me.

Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in most U.S. foster children losing their visits indefinitely, with little effort by child welfare agencies to reduce negative impacts on the well-being of foster children or on their families’ ability to reunify.

U.S. juvenile courts’ shallow response to the COVID-19 pandemic

Foster youth are being abandoned by the state during this time of crisis. Think about how difficult a time this is for any child.

Now, imagine being quarantined indefinitely as a foster child where you have no idea when you will see your parents next. As statewide shutdown orders sweep through the nation, child welfare agencies and juvenile courts are, by and large, treating foster children and system-impacted families with sheer indifference. Most COVID-19 juvenile court orders, if any exist at all, merely address court closures and give brief statements that parent-child visitation is suspended indefinitely.

For example, the orders posted in Washington State on the King County Dependency Court website addressed court closures, continuances (postponement of court hearings) and agreed orders (orders that can be sent to the court electronically for approval without a hearing). However, the order does not address parent-child visitation, court-ordered service requirements or statutory timelines.

The Williamson County Juvenile Dependency Court in Tennessee has closed until April 30 with no provisions made to ensure continued parent-child visitation. An emergency order issued by the Tennessee Supreme Court does allow for in-person court proceedings related to emergency child custody or visitation orders, but we have yet to see if any Tennessee children will actually be released to the custody of or to be quarantined with their parents.

Parents in Oregon and Alabama report similar issues with having their in-person visitation canceled, meanwhile still being expected to satisfy court-ordered service requirements and without any relief on statutory timelines. Kim Farranto has a case out of Shelby, Alabama. Farranto said, “I believe this crisis is hurting everyone’s cases here in Alabama because we can’t see and hug our kids, we still need to engage in our services, and the clock is still ticking away on our cases.”

Currently, San Francisco has the most reunification-oriented COVID-19 child welfare orders in place that I am aware of, although even those orders fall short of providing meaningful relief to foster children because they fail to set clearly defined visitation orders to ensure that parent-child contact is maximized. While the order has a provision that allows parents already on unsupervised or overnight visitation to be quarantined or reunified with their children without a court order, this provision is discretionary.

For the most part, San Francisco foster children are getting teleconferencing visits in lieu of in-person visits just like most other foster children in the nation – a necessary measure given the essential social distancing protocols that are currently in place. The emergency order, which was issued by San Francisco Juvenile Court Supervising Judge Monica F. Wiley, is more comprehensive than most other orders issued thus far by juvenile courts and attempts to protect at least some fundamental rights of parents and children.

Perhaps most notably, the order extends statutory reunification timelines.

According to the federal Adoption and Safe Families Act (ASFA), if a child has been in foster care for 15 of the most recent 22 months, state courts must move to terminate parental rights. Without extending these ASFA timelines, an obscene number of parents will be at risk of having their children adopted out as a direct consequence of the COVID-19 shutdown orders.

Over the past week, new guidance has emerged at the federal level to address this issue. Jerry Milner and David Kelly from the U.S. Children’s Bureau at the Department of Health and Human Services wrote in an article published by The Chronicle of Social Change: “We cannot allow the coronavirus to serve as a modern-day orphan train that leads to the redistribution of other people’s children.”

The article acknowledges the “structural, functional, and funding limitations” the current crisis poses on parents and reinforces the importance of maintaining parent-child bonds. However, we have yet to see how these issues will be resolved, if at all, in jurisdictions across the United States.

Families across the nation struggle against anti-family climate

Contra Costa County is roughly 18 miles east of San Francisco, and yet its child welfare policies in the face of this crisis are lightyears more punitive and less progressive. For example, Contra Costa offers just one hour per week of parent-child visitation time compared to six hours in San Francisco. And now, in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, Contra Costa Children and Family Services and the Contra Costa Juvenile Dependency Court remain as anti-family as ever.

Surveying system-impacted parents is part of the work I do through my organization, California Rise: We interview parents on their cases and track data and patterns. Of the dozens of Contra Costa system-impacted families I have interviewed, all have been tossed to the side and left in the dark, their needs and the needs of their children seemingly irrelevant. They have simply been told that court and visitation is suspended indefinitely, with no virtual visits available.

Michael Flynn Sr.’s granddaughter is currently a state ward. His daughter, Christina Flynn, has a documented history of seizures and no history of drug abuse. Several months ago, one of her seizures landed her child in foster care and thrust her family into a never-ending nightmare.

When paramedics arrived on the scene after Flynn had experienced a seizure, they automatically assumed the seizure was the result of a drug overdose, according to Flynn Sr. They did not drug test her.

This assumption triggered the removal of her 8-year-old daughter. Since the case opened, insurmountable and often senseless obstacles have been placed before the Flynn family. Every effort evidencing Christina Flynn’s fitness as a mother and of her well-documented seizure disorder has been disregarded.

The family has sunk every cent they have into their legal defense, and yet, the family has been deprived time and time again of their day in court. There have now been seven continuances, each with no notice.

And now, since the COVID-19 crisis has hit, they missed the child’s eighth birthday, videoconferencing visits have been canceled with no explanation, no one from the department will answer any of the family’s questions, and they have no idea when they will be able to get back into court to fight these charges.

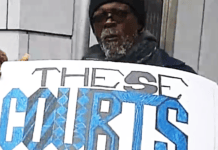

“I just want to see my granddaughter,” says Flynn Sr. “My family has been waiting for months now just for the right to fight our case, and now the courts are shut down and I can’t even get answers to questions like, ‘Does my granddaughter have coronavirus?’ My daughter is innocent of the charges against her, and we can prove this. But now the whole system is shut down while my granddaughter rots in foster care.”

What is happening to this family is not unique to Contra Costa County. Parents all across the nation are having their cases put on hold indefinitely and their visits suspended in lieu of teleconferencing – in many cases, with few adjustments made to the timeline for reunification.

Parent-child bonds grow dangerously thin during times of such distance and uncertainty, and when the timeline for reunification is not automatically extended, parents risk losing their children permanently because they were not able to visit during this period of social distancing. With each day that passes during COVID-19 shutdown orders, parents find themselves increasingly further away from getting their children back.

A public policy plea in the best interests of children

There are so many questions currently left unanswered; so much that can go wrong. If swift action is not taken to develop and implement compassionate and comprehensive COVID-19 measures – policies developed with intention of protecting the fundamental rights of children and families – then countless families are at risk of being annihilated.

This is a public policy plea for every state government to issue comprehensive child welfare guidelines in light of COVID-19 and to issue clear directives to local jurisdictions to this end.

Erin Miles Cloud is the former supervising attorney for the public defender nonprofit Bronx Defenders and co-founder and co-director of Movement for Family Power, a national parents’ rights advocacy organization.

“Child Protective Services (CPS) is failing – as it always has – to provide a social safety net and support to families who need it most. CPS is a threat to the fundamental rights of parents, especially Black and Brown parents, to have healthy, happy and safe families that remain together,” Cloud told Truthout.

“We have an opportunity here to divest from this harmful system and redirect resources to community-based organizations and initiatives that are helping meet the needs of families without threatening punishment of dissolution. Now, more than ever, families need support, not separation.”

“The most troubling trend we are seeing is the abrupt end to physical contact and in-person visits, which will definitely put reunification at risk. We are also seeing courts halt access to challenge child removals, which is blatantly unconstitutional. There is no clear guidance for what expectations are for parents around compliance for service plans,” says Lisa Sangoi, also a Movement for Family Power co-founder and co-director.

“Agencies and courts have been able to issue so many orders around visitation and court appearances, they have yet to suspend the ASFA timelines. So you have families that can’t see their children for long periods of time and are very worried that this will be held against them when their ASFA timeline is up in 15 months.”

Michelle D. Chan is a writer, activist and founder and director of California Rise (formerly Parents Against CPS Corruption). She can be reached at mchan46@outlook.com.

Copyright, Truthout.org. Reprinted with permission. This story is part of the series Despair and Disparity: The Uneven Burdens of COVID-19.

Store

Store