Tetra Tech was part of a team of contractors hired by the EPA to clean up a toxic radioactive dump in Ohio but evidence suggests EPA implemented a cover-up instead of a cleanup, creating a playbook for institutionalizing corrupted science across the nation. When Tetra Tech got busted years later for fraud at another radioactive site, in San Francisco, the EPA’s failure to demand best scientific practices was exposed again with dire ramifications for public health.

by Greg M. Schwartz

Government contractor Tetra Tech was paid more than $250 million by the Navy to clean up the former Hunters Point Naval Shipyard (HPNS) on the edge of the San Francisco Bay, including removal of radioactive waste to clear the way for lucrative real estate development projects. But the cleanup came to a halt after the firm was discovered to have engaged in systematic fraud at the site.

The Department of Justice has joined a whistleblowers lawsuit against Tetra Tech after those employees were fired for reporting how their supervisors had falsified results of testing for radiological remediation. Tetra Tech has denied the allegations by blaming the fraud on “rogue” employees, while continuing to rake in hundreds of millions of dollars in new government contracts across the nation.

Reams of documents and stakeholder interviews have shed light on how a flawed cleanup at an obscure landfill in Ohio – where Tetra Tech was also in the middle of radiation testing controversies – became a model for EPA’s work nationwide. Did the EPA’s lack of scientific accountability years ago in Ohio ultimately lead to the massive eco-fraud in San Francisco? Below is Part 1 of a four-part series.

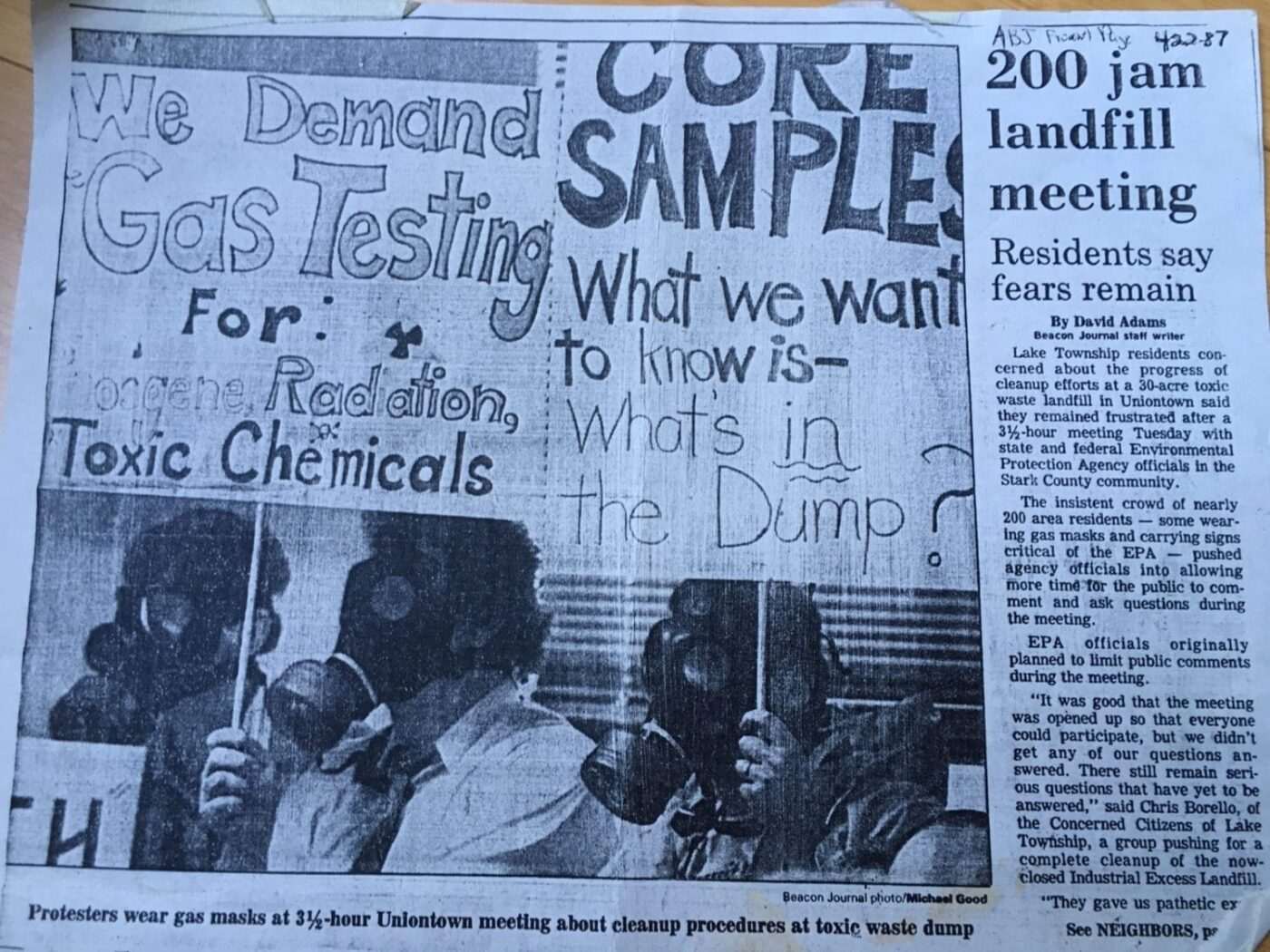

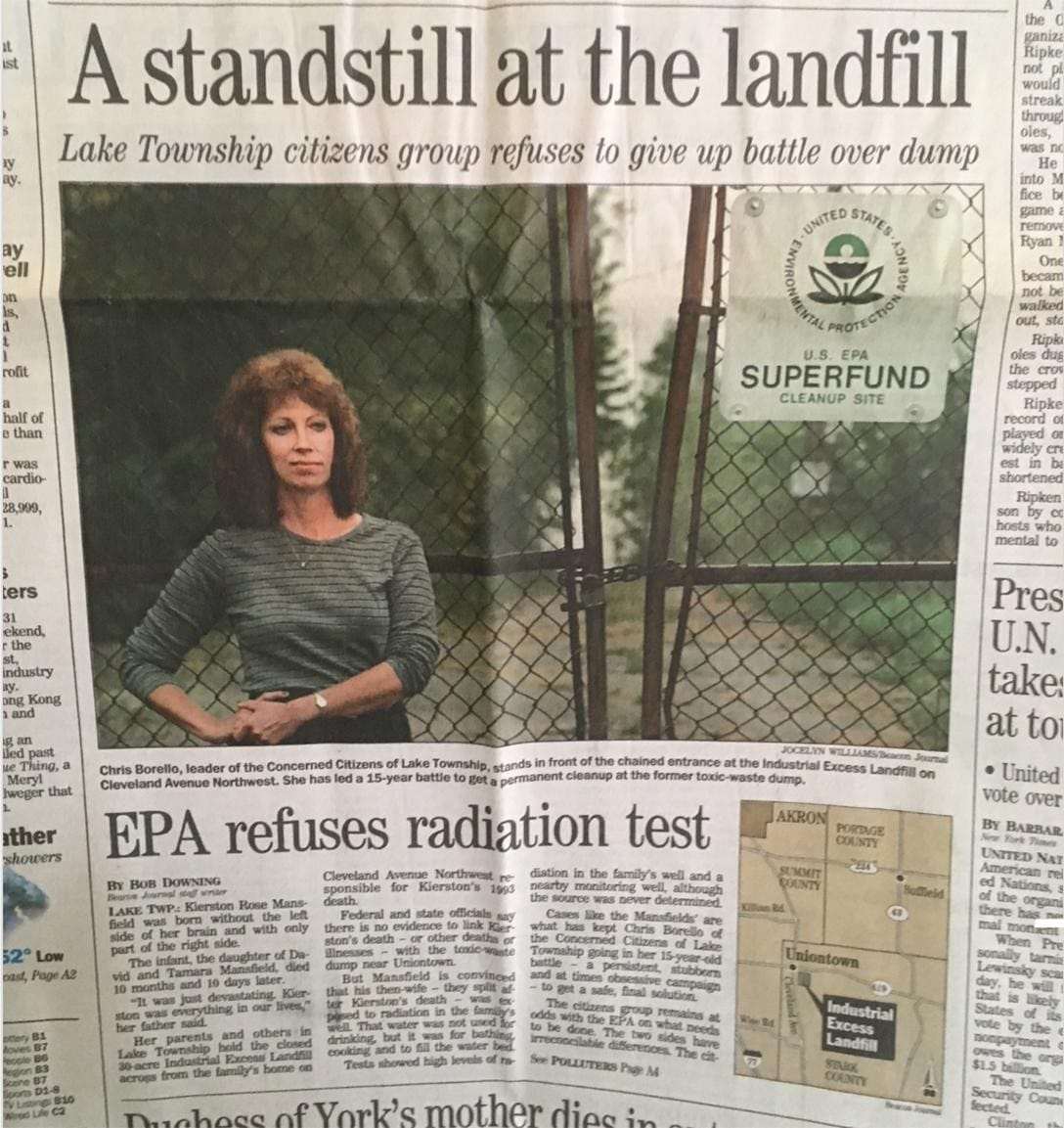

When longtime Ohio activist Chris Borello first heard about a new investigation into Tetra Tech’s role in the radiation scandal in San Francisco that has been called “the biggest case of eco-fraud in US history,” she immediately recalled the same contractor’s mistake-laden past in her own community’s backyard.

Borello lived in Northeast Ohio, 2,500 miles away from San Francisco, but right near a toxic radioactive waste dump called the Industrial Excess Landfill (IEL) about halfway between Akron and Canton in Uniontown. Hunters Point is about 20 times larger than the IEL but the two sites have a lot in common – the dumping of radioactive wastes that federal and state agencies failed to clean up. Tetra Tech was curiously involved in radiation testing controversies at both sites.

The Ohio landfill has been embroiled in controversy for decades, but few outside of the Buckeye state have heard of it. Borello founded Concerned Citizens of Lake Township (which Uniontown falls within) and has remained steadfast in her activism for more than 35 years, refusing to give up her quest for a safe cleanup and the truth about the health threats posed to the surrounding community. This dogged dedication to environmental justice has led some reporters to describe her as “the Erin Brockovich of Ohio.”

Borello pulled up a document in the spring of 2018 confirming that Tetra Tech’s fraud at Hunters Point in San Francisco had in fact been preceded by their questionable field work at the IEL in the 1990s, catalyzing a renewed investigation into the contractor’s role at the Ohio landfill. With the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) now proposing to allow some radioactive waste to be disposed of at municipal landfills, the IEL saga offers a timely reminder of why such a proposal is a terrible idea with dire ramifications for those who live near such locations.

The site was originally a sand-and-gravel quarry but was operated as a dump from 1966 to 1980, when a handful of well known Akron-area rubber corporations were among clients who disposed of their hazardous industrial wastes at the landfill. Congress passed the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation & Liability Act in 1980, which was created to enable the EPA to manage “the cleanup of the nation’s worst hazardous waste sites.” Better known as the Superfund law, the act gave the EPA the authority to force polluters, called PRPs (potentially responsible parties), to pay for remediation of such sites.

EPA placed the IEL on its National Priorities List for cleanup in 1984. The 30-acre site in Lake Township was ranked “worst” in the heavily polluted Midwest for groundwater contamination at the time. (Groundwater meaning underground, as opposed to on the surface.) The IEL curiously became the EPA’s “case in point” regarding testing methodology for radiation issues at Superfund sites nationwide, with Tetra Tech contracted to handle much of the fieldwork.

The year before IEL was designated as a Superfund site, Borello and neighbors were making crafts for sick children hospitalized at Akron Children’s Hospital in 1983 when she raised the topic of water contamination in the nearby communities of Hartville and North Canton because the issue had been highlighted in a TV news story. Her neighbor informed her that she’d been using bottled water for some time because of concerns about the nearby landfill just up the road.

Because everyone in the community was on private well water, Borello became alarmed and contacted the Ohio EPA the next day. The agency informed her that the IEL was on a list of sites around Ohio to be investigated for hazardous waste disposal.

Shortly thereafter, another neighbor informed Borello about a series of miscarriages including her own, adding that she’d begun to wonder if there was a connection with the landfill. She and another mother who had lost twins in a miscarriage raised the topic at the next Lake Township Trustees meeting. “That’s when all hell broke loose,” Borello says.

Citizens were soon further dismayed to discover that local officials were aware of the dumping of 11,000 gallons of liquid waste per day when the dump had been in operation.

Troubling eyewitness accounts from the past

Borello quickly formed Concerned Citizens of Lake Township (CCLT) by going door to door, where she heard multiple accounts of life-threatening diseases. On some streets, there were cancers in nearly every home. She also began hearing eyewitness accounts from old-time residents about something far more ominous: trucks coming into the landfill late at night bearing cargo with radioactive symbols.

Lizette and Harlan McGregor described how “many trucks came into the landfill in the early ‘70s … loaded with 50 to a hundred stainless steel canisters with ‘hazardous’ markings on them … The tankers would come in all through the night and dump.” Lizette eventually died of cancer that she blamed on the landfill.

“There were rings and rings of radiation-induced deaths around the landfill.”

Another eyewitness, Rex Shover, said at a later public meeting that during his time as a volunteer fireman he “personally saw tanker trucks carrying ‘radioactive’ insignia enter the Industrial Excess Landfill late at night after the landfill was closed.” Shover’s brother Jim had worked summers at the IEL before joining the Navy and also witnessed the mysterious trucks:

“During his Navy career, Mr. J. Shover received training in nuclear warfare, industrial radiology, radioactive materials, and associated health problems in humans, and served on the Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical rapid response team, making him uniquely qualified to identify military vehicles and radiation symbols … He identified the trucks as ‘specially-designed double-lined tankers designed to transport liquid radioactive waste material.’”

Charles Kittinger, former co-owner of the IEL, told a federal court 30 years later the following eerie tale: One winter’s day back in 1969 or 1970, a truck arrived accompanied by two cars with military personnel. They told Kittinger they had to get rid of some huge metal “eggs.” Kittinger explained:

“Someone had called in advance and asked if they could dump them, and I said I think it’s permissible since it’s metal. I witnessed two eggs being dumped. They said they’d be safe as long as no one tried to cut into them. One of them said that in 30 years they’d be dissipated and there wouldn’t be any radiation left in them.”

One of the men in an Army uniform instructed Kittinger never to mention the eggs to anyone.

Government agency denies cancer cluster

Uniontown’s 2,800 mostly working-class residents were especially worried about the unusual number of cancer cases and birth defects near the IEL. A house-to-house study revealed 120 residents reporting cancers, birth defects and neurological defects within two miles of the site. But firmly establishing a specific cause for cancer and other such health issues is typically difficult.

Blanton Beltz, who grew up near the southern edge of the landfill, was a case in point. He had been one of Borello’s first grade students at Uniontown Grade School, located just north of the dump, and later developed bone cancer in his leg. Beltz died in 1991 at age 21. His parents sued 18 PRPs for exposing him to the radiation and toxic chemicals suspected to have killed him. His case was referred to Dr. Elaine Panitz, MD, an expert on occupational medicine who had trained at Harvard.

“I have reviewed materials suggesting radiation contamination of the IEL site and surrounding groundwater,” Dr. Panitz wrote to the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), which was created by the Superfund. This agency was tasked with the mission “to investigate environmental exposures to hazardous substances in communities and take action to reduce harmful exposures and their health consequences.”

Panitz went on to state that in her professional opinion, the case presents “disturbing evidence” that radiation may be causing cancers surrounding the IEL site with routes of exposure including ingestion, skin absorption and inhalation. Panitz followed by definitively diagnosing Beltz’s cause of death as having been “caused by radiation exposure through groundwater contamination.”

Borello says that Panitz also personally conveyed to her a disturbing opinion: “There were rings and rings of radiation-induced deaths around the landfill.” This observation further drove Borello’s pursuit of the truth.

The EPA tasked the environmental engineering firm PRC/Tetra Tech (Planning Research Corporation, a company acquired by Tetra Tech) at the end of 1989 to oversee removal of barrels of waste generated by the remedial investigation and then to start sampling groundwater at the IEL in 1990. The EPA referred the company’s lab analyses to ATSDR. These analyses were only based on PRC/Tetra Tech’s occasional sampling of just nine residential wells over a period of four years, from 1990 to 1993.

ATSDR rejected the survey’s suggestion of a “cancer cluster” around the IEL, but the PRPs still settled with the Beltz family for an undisclosed sum in 1994. The family of another cancer patient, Cheryl Clark, also settled privately in 1995 but the terms were sealed by the court.

Dr. Marvin Resnikoff, a scientist hired as an adviser to Uniontown’s residents, was highly skeptical of the agency’s conclusions. He pointed out that an Ohio EPA test of a monitored well had revealed radiation levels 140 times the naturally occurring rate. He also told local media: “Once ATSDR comes in they’ll say there is no connection. I can guarantee they will whitewash the whole thing. That’s the natural progression wherever there are [cancer] clusters. ATSDR comes in and says everything is OK.”

Years later, a congressional report ripped ATSDR as an agency that “often obscures or overlooks potential health hazards, uses inadequate analysis, and fails to zero in on toxic culprits … time and time again ATSDR appears to avoid clearly and directly confronting the most obvious toxic culprits that harm the health of local communities throughout the nation.”

Instead of a serious epidemiological study of the possible causes of the cancers, the community got years of runaround and evasion. In the early stages of investigating the landfill, the EPA’s contractors found that methane and other gases had built up to dangerous levels underground. The EPA then hired an emergency response team in 1984-85 that documents suggest included Tetra Tech to devise a system to actively pump up and ventilate gases from the site so that adjacent homes wouldn’t be at risk of explosion from methane migration.

Such a system was implemented, but was limited in scope. The criteria were narrowly defined to mitigate explosive levels of volatile gases to keep border homes from exploding, which did not include lower-level exposures from toxic vapors. The EPA’s emergency response officials told CCLT that their hands were tied since their directive was limited to only addressing imminent threats.

ATSDR and the Centers for Disease Control had in fact urged in 1989 that the EPA adopt an expansion of the original gas control system to address the issue of toxic vapors migrating from the site undetected. This proposed upgrade was stymied for more than a decade, with the EPA ultimately rejecting implementation altogether and even bowing to the polluters’ wish in 2005 to shut down the old system – despite independent experts’ estimate from PRC/Tetra Tech’s 1991 data that the IEL generates 150 tons of toxic gases yearly, excluding methane.

The emergency response team’s report to EPA included a sworn affidavit by an IEL employee who had witnessed burial of 55-gallon drums of waste. The report’s appendix included a list of “possible generators” of hazardous waste at the IEL that included Goodyear Aerospace, a company then engaged in secret work for the government on nuclear centrifuges and fuel for nuclear reactors.

While it was initially presumed that these drums came from Goodyear’s Akron plants, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) later suggested otherwise. The NRC even reached out to Borello in 1994 to grill her about radiation concerns at the IEL, in the context of their own investigation of the nearby Wingfoot Lake centrifuge facility operated by Goodyear Aerospace.

The contractors reviewed the dump owner’s logs, and the EPA demanded records from the companies that dumped at the IEL and then compiled a long list of “contaminants of concern.” Among the contaminants acknowledged were tons of coal ash from the rubber companies.

Elevated radon levels were found at the tail end of the remedial investigation by Dr. Sid Page of C.C. Johnson and Maholtra, EPA’s primary contractor at the IEL during the remedial investigation phase. Where the elevated radon from the IEL gas vents came from remained a mystery, yet EPA signed the 1989 Record of Decision (ROD) on the cleanup without doing any further sampling.

Despite the eyewitness accounts, the EPA maintained the premise that since there was no official record of radioactive wastes dumped at the IEL, testing for radiation wasn’t needed. But when five years of public outcry finally forced the EPA to test in 1990, back-to-back rounds conducted by two different commercial labs reported radiation including man-made isotopes.

The EPA invalidated both rounds, though, asserting a number of mistakes in the field work performed by PRC/Tetra Tech including using the wrong type of jars. But subsequent tests in 1991 and 1992 were declared valid for radiation, including man-made plutonium. PRC/Tetra Tech had officially been brought on board by the EPA in 1989-90 to carry out the post-ROD field work at the dump – after the EPA had initially stated it would be hiring the Army Corp of Engineers to do the field work.

Meanwhile, the water supply of up to 600,000 Ohioans was under threat, according to independent scientists.

If you don’t look, you won’t find

While grave concerns swirl around what actually got buried at the IEL, another critical question remains regarding the truth about the flow of contamination as the site continues to flush freely into the aquifer. Controversy surrounding the site’s flow direction centered around whether or not potential contamination was flowing south toward the municipal well fields that serve thousands of people.

After Dr. Sid Page of the EPA’s Remedial Investigation/Feasibility Study contractor – CC Johnson & Maholtra – had originally told residents at a town meeting that the flow went exclusively southwest along the Metzger Ditch stream toward North Canton, the official statement got inexplicably switched to “exclusively straight east to west.” ATSDR dared to challenge the EPA by subcontracting the US Geological Survey (USGS) from the Department of the Interior in 1988, leading to a USGS report in 1989 indicating that groundwater from the site “moves in a radial pattern away from the site in all directions.”

The EPA basically ignored these findings. In a meeting with ATSDR at the Uniontown fire station to discuss the agency’s draft public health assessment in 1988, Borello recounts how one top ATSDR official took the arm of a CCLT member and urged: “Don’t let them EVER tell you that it doesn’t go in all directions.”

Dr. Mark Bashor, ATSDR’s head of risk assessment, had been the one who persuaded EPA Region 5 in 1989 to include language in the cleanup’s ROD that expanded upon the gas control system for preventing toxic vapors from moving off the site into neighboring homes. Bashor and ATSDR were also instrumental in getting border families evacuated to hotel rooms and ultimately permanently relocated. But when Borello called Bashor at the end of the summer of ‘89 to inform him about the death of one of the evacuees, he told her that he could no longer help Uniontown since he’d been removed from his position and reassigned.

Borello and another CCLT board member were later flown to D.C. in the spring of 1991 to participate in an ATSDR roundtable meeting of citizens from Superfund sites around the country. During a break, she and two other participants had a chance to converse with ATSDR administrator Dr. Barry Johnson in the hallway, where he related some troubling information.

“It is my belief that we [ATSDR] were punished $15 million for helping Uniontown,” Dr. Johnson said, indicating that the funding had been cut by the EPA.

Stunned by this revelation, Borello asked, “Dr. Johnson, do you mean you were punished for hiring USGS, refuting Region 5 on the groundwater flow, and for triggering the evacuation of border residents?”

Johnson nodded and affirmed, “Yes, that is my belief.”

Pressed on the groundwater issue by CCLT and others, EPA Region 5 ultimately relented and hired USGS itself to review water level data interpretations made by PRC/Tetra Tech during design phase studies. The USGS report produced in 1993 again challenged the EPA and PRC/Tetra Tech. USGS confirmed that groundwater flows radially from the IEL and criticized PRC/Tetra Tech for omitting important data points related to the uppermost shallow monitoring wells, which could have resulted in seriously flawed conclusions.

Borello says EPA gas expert Dr. Henry Schuver informed her how important those wells were in garnering critical information regarding potential toxic vapor migration. Her group was therefore horrified when Region 5 allowed the polluters to seal up many of those same test wells in 2004, preventing additional sampling for either water or gases.

When the EPA permitted the polluters to bring in their own contractors to conduct field work starting in 1997, the USGS findings on radial flow were supported by PRP contractor Geraghty & Miller Inc., whose analysis confirmed radial flow. “Fig. 3-2 & 3-3 show the localized radial flow of groundwater from the site … Radial flow to the east and southeast is toward Metzger Ditch, while flow to the west is generally consistent with regional flow patterns.”

“ . . . where are the metals, including the radioactive ones, going … ? How many years – decades – centuries – millenniums will they leach and to where? . . .”

This finding appeared to reiterate Dr. Page’s original analysis that site waste could travel toward the stream – which first goes southeast before turning southwest toward North Canton.

But the PRPs then hired a different field contractor – Sharp & Associates – in 1998, whose studies ultimately excluded many of the same uppermost shallow test wells that PRC/Tetra Tech had omitted. This appeared to enable recharacterization of the flow back to the linear east-to-west direction.

CCLT expert consultant Dr. Julie Weatherington-Rice, from Ohio State University and the consulting firm Bennett & Williams (B&W), took issue with the work done by Sharp & Associates in both her 2005 and 2006 reports on the IEL. Rice reiterated some of these key concerns in a 2011 email memo to the Ohio EPA, saying that Sharp’s work “was fatally flawed.”

“In fact, there were a number of monitoring wells considered ‘clean’ for 10 years that were abandoned as a result,” she wrote. “When B&W later reviewed the water chemistry, it was found a number of those ‘clean’ wells were, in fact, contaminated, but it was too late, because they were already closed.”

Weatherington-Rice further wrote: “Given the nature of the coal ash sitting in the uncovered, unlined pit of sand and gravel, one can only ask, where are the metals, including the radioactive ones, going … ? How many years – decades – centuries – millenniums will they leach and to where? This doesn’t even consider man-made materials loose and/or in barrels remaining within the site that have not yet been breached.”

If readers find the groundwater flow issue clear as mud, they will begin to understand how Uniontown residents have felt over the years. Many still wonder if North Canton’s water could be contaminated by toxic pollutants from the IEL.

Water management has been one of Tetra Tech’s specialties since its founding and the company boasts that its involvement in the Superfund program “expanded significantly“ with the acquisition of PRC-EMI. Yet curiously, the IEL isn’t mentioned in the company’s corporate history.

There’s also a strange anomaly surrounding the question of when Tetra Tech acquired PRC. The company’s 50th anniversary history booklet from 2016 dates the acquisition of PRC to 1985. But other public records indicate that the purchase occurred in 1995. (Tetra Tech’s PR department failed to respond to multiple email queries regarding this odd discrepancy.)

Another cautionary flag comes from a 1989 GAO report on the Superfund program titled “Contractors Are Being Too Liberally Indemnified by the Government.” The report revealed that an audit of suspicious Superfund contracts showed that the EPA had indemnified PRC against any liability for negligence in its work at the IEL and other sites.

The GAO report warned that if EPA contractors screwed up, the agency and the taxpayers would get stuck with the tab. EPA contractors were thus given motivation to do jobs quicker and cheaper, rather than thoroughly with the best available science. An additional GAO audit found that conflicts of interest with PRC in 1985-86 were repeated in 1991, noting that the EPA “has acknowledged many of the problems GAO has reported, but has not addressed them sufficiently to actually correct the problems.”

When EPA hired PRC/Tetra Tech after issuing the Record of Decision in 1989 to address multiple data gaps not addressed during the remedial investigation at the IEL, the firm was also tasked to design the three components of the cleanup. This included gathering additional information from field studies, beyond just water sampling to also address soil and gases. “Containment” became the EPA’s strategic remedy, rather than the more expensive removal and restoration option desired by the IEL’s neighbors.

Investigative reporter Greg M. Schwartz has covered public affairs for outlets including the KPFA Evening News, Cleveland Free Times, San Antonio Current, Austin Bulldog and Ecowatch.com. His 2009 “Crime Scene Cleanup” story on San Antonio’s “toxic triangle” area won a Lone Star Award for investigative reporting from the Houston Press Club. He can be reached at greg.m.schwartz@gmail.com or Twitter.com/gms111.