by Art Hazelwood

Ronnie Goodman passed away in early August this year. He died on the street, just after his 60th birthday, on the same corner where he’d been living for more than a year. We stood around waiting for the medical examiner to come and take him. The cops had put a sheet over him.

Someone, thinking the cops were harassing Ronnie, sprayed the police car with a fire extinguisher coating it with a white powdering of dust. People came up and burst into tears. A construction worker walked over expressing surprise, “I just talked to him yesterday.”

Ronnie was charismatic, joyful, artistic, but he had also suffered deeply. He was mourned by many and a makeshift altar was created at the corner where he had amassed his art supplies, his half-finished paintings and his piles of junk.

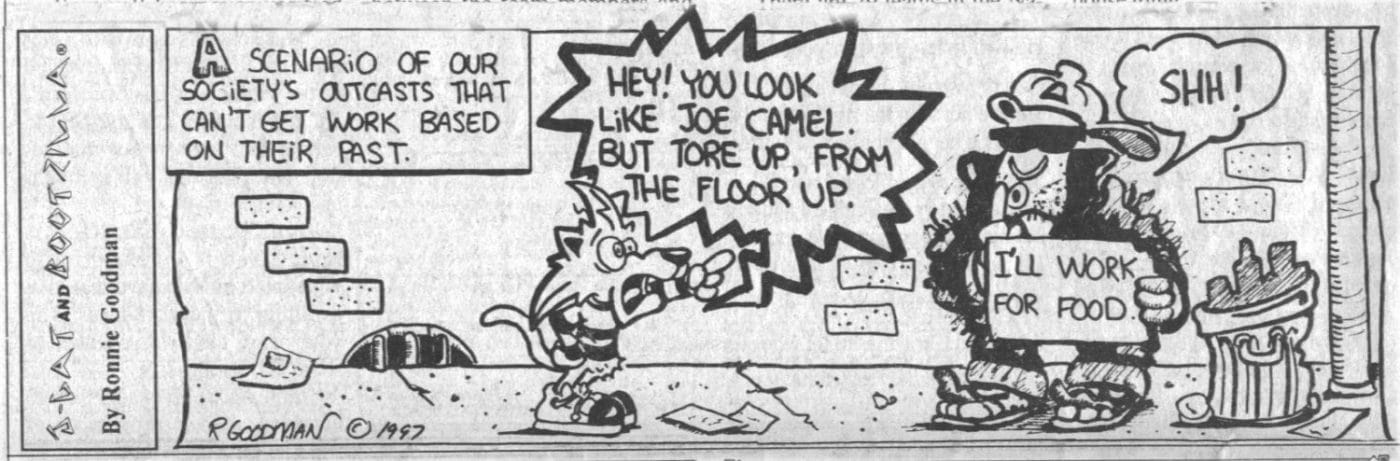

Ronnie’s great achievement was in overcoming so many obstacles to create powerful artwork that addressed two of the darkest and most neglected aspects of American life, prison and homelessness.

To many, Ronnie was a wild eccentric inspired street artist. But this is only the last part of his life. Before that, when he was at his best, Ronnie was a disciplined, focused, thoughtful and emotionally attuned artist. He was a strong athletic marathon runner. But he was also tormented by addiction.

Ronnie’s great achievement was in overcoming so many obstacles to create powerful artwork that addressed two of the darkest and most neglected aspects of American life, prison and homelessness. He lived those experiences. He was a Black man, an ex-con, an addict and homeless.

It wasn’t only his own experience that gave his work such power, but a deep compassion for others that propelled his work. His work represented the difficult life he and his community lived, but within all his work there was a note of hope, and a sense of the power of art – often represented in the form of music – to make the suffering of life bearable.

Among artists working in prison, artists living in poverty and homelessness, it is rare to find someone who faces that situation directly in their art. Ronnie looked straight at the truth.

I met Ronnie at San Quentin State Prison when I was coming in as a regular guest artist in the printmaking class of Katya McCulloch. We began our first collaboration on a project for the Western Regional Advocacy Project (WRAP) to draw attention to the link between homelessness and incarceration. I provided Ronnie the information, the details, the statistics, and Ronnie created the art that incapsulated those cold facts in real life form. That began a long period of working together on linocut prints. After his release from San Quentin in 2010 we worked together almost weekly on printing at my studio for five years.

Ronnie was largely educated in prison. He heard Malcolm X cassette tapes in prison. He began making cartoons for the Black-owned newspaper San Francisco Bay View while in prison. In fact, it was because of his desire to make cartoons that he learned to read and write while in prison.

Ronnie had art teachers at four separate prisons in California. Those dedicated teachers, provided through the Arts in Corrections program, taught Ronnie lithography, drawing and stencil printing. Later at San Quentin he studied printmaking with Katya and painting with Patrick Maloney.

When he was paroled to San Francisco, he worked in the studios of Hospitality House Community Arts Program, a studio open to low income artists. In between his years in prison Ronnie worked on murals with Precita Eyes Mural Arts and studied etching at Mission Grafica with Ali Blum.

Ronnie wasn’t a lone artist genius. He was a part of the community deeply embedded in the artistic as well as the social struggle. In addition to creating prints and designs for WRAP, he created work for the Coalition on Homelessness. We recently used one of his linocut prints, “Hands Up Don’t Shoot,” for a poster to lead an action to oppose police harassment of especially Black and Brown homeless people.

In 2014, Ronnie ran the San Francisco Marathon as a fundraiser for Hospitality House, raising thousands of dollars for their programs to support homeless people. He was generous and committed to the community.

The largest and one of the final print projects Ronnie worked on was a three-panel linocut measuring 24 by 72 inches, “Three Apostles of Jazz.” He was invited in 2014 by Mullowney Print Studios to create this large scale print for an exhibition of large scale prints, XXL Relief. Paul Mullowney showed Ronnie new ways of printing that were opening Ronnie up to all sorts of new possibilities.

In 2015, Ronnie Goodman and I had a two-person show at the Georgia Museum of Art. But by then his ability to create work, to focus on the fine detail that his work always had, was becoming clouded by his addiction.

In that same year Ronnie’s son had been murdered. He never spoke to me about the chain of events that led to his return to addiction. Several of us tried over the years to get him to allow us to help him. He refused, got angry, threatened, withdrew.

Ronnie looked straight at the truth.

He lost much of his community, and he rarely made art. What he did make was nowhere near the heights he had reached. He demanded his artwork back from people who had bought it. He demanded the linoleum blocks that I was storing for him back from me. He sold some on the street for nothing; the rest was confiscated by the city in their relentless sweeps of homeless people’s belongings.

There is precious little left of the legacy he created. His great dream to show all his prison work together in a proper venue: his charcoal portraits of fellow inmates, his oil paintings of the yard, of the guys passing time or living through desperate moments, his linocuts of baseball in Folsom, jazz at San Quentin, light streaming through the bullet holes in the roof of a building at San Quentin … much of it gone, trashed on the street, damaged and discarded. A few people bought things. A few institutions bought things. Georgia Art Museum acquired several prints from Ronnie. The Library of Congress has a collection of prints as well.

There was a final brief spurt of creative output made possible by the streets being emptied and the shops being boarded up due to the pandemic. Ronnie suddenly saw the blank canvas of his streets and his creativity came back. He painted several murals, including a self-portrait.

He wanted to make art again and was excited and more engaged than he had been in many years. He was in a turf war with taggers who were taking over the walls as well. He wanted to make art. They wanted to tag walls. Within a week of his death his self-portrait had been totally covered in tags.

Ronnie left us with precious little of his work. But what he created was a testament to his vision of the overarching power of art to make life bearable, at times beautiful.

Art Hazelwood is an artist with a focus on political printmaking. For over 25 years years he has worked with homeless rights groups in the Bay Area and beyond. He has taught at San Quentin and the San Francisco Art Institute, where he is the union shop steward for adjunct faculty. Visit him at www.arthazelwood.com and contact him at art@arthazelwood.com.