by Talib Williams

The Bay View is serializing the introduction to “Annotated Tears, Vol. 2,” by Talib Williams, who is currently incarcerated in Soledad, California, and has written the history of that storied place. In the spirit of Sankofa, we learn the past to build the future.

I was going to relay the tragedy that was the death of George Jackson in a linear fashion, but there are so many twists and turns that the reader could easily get lost. The popular report says that, in an attempt to escape, Jackson smuggled a gun into the Adjustment Center at San Quentin, taking charge and releasing inmates to assist in his takeover. This resulted in the gruesome murder of three white guards, two white inmates, and Jackson himself being gunned down as he ran across the yard, gun in hand, attempting to escape.

But David Johnson, one of the inmates charged with conspiracy and other charges related to this event said in an interview published by the San Francisco Bay View:

“George was manipulated into a situation where they could take the opportunity to assassinate him, but in the process three guards and two white inmates got killed. So to cover up George’s assassination, six of us got charged with trying to escape, possession of explosives and weapons, and conspiracy, and we became known as the San Quentin 6.”

So, instead of telling the story of what happened in what became known as the San Quentin Massacre, I’ll quote a 2017 article published in Prison Legal News by Dan Berger in order to highlight a larger point: that the murder of George Jackson has a direct correlation to the way in which Black men are treated throughout California’s Department of Corrections:

“It is not the last month in Ferguson, Missouri. It is not Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Ezell Ford, Roshad McIntosh or any of the other unarmed Black men killed by police in recent weeks, though it could be. It is San Quentin, California, in the year 1971. His name was George Jackson. Though more than four decades have gone by since he was killed, his life and death signal the ways in which this country’s macabre routine of police violence against young Black men and women has become institutionalized throughout the criminal justice system.

“With Jackson, as with the others, the deaths marked not just the tragic end of a young life but also the bizarre beginnings of speculation about the character of the deceased. Jackson, an activist and bestselling author, was killed at California’s San Quentin prison on Aug. 21, 1971, by two guards who fired down at him as he ran toward the wall surrounding the prison after a 30-minute takeover of a solitary confinement unit. Unlike the unarmed youth killed by police, Jackson did have a gun on him when he was killed. Yet the circumstances surrounding his death remain mysterious, including how he managed to get his hands on a gun. How he managed to acquire it in the confines of what was then one of California’s toughest prisons remains a mystery, especially since authorities kept changing their story about the caliber of the gun and its origins. Was it smuggled in or did he wrest it from a guard who was about to kill him?

“One thing is clear: Jackson’s intransigence and the open-ended questions that surround his death make him a relevant figure in the age of mass incarceration and rampant police violence. His place in history has been secured largely according to one’s political perspective. To some, he is a martyr of political injustice, like Sacco and Vanzetti a half-century before him. Every year, thousands of college students meet George Jackson as an author, someone whose raw eloquence captures the prison experience like few others. And to others, Jackson is an exaggerated bad guy, famous for being infamous and a hustler to the end.

“Depending on your outlook, Jackson is some combination of these. But he is also something else: a specter haunting the American criminal justice system, a trenchant critic even from the grave. Whether as boogeyman, hero or martyr, George Jackson remains prominent in prison America. Indeed, if the 1953 execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg was the dystopic expression of Cold War anxieties, the 1971 killing of George Jackson marked the onset of a new era of mass incarceration and the hyper-policing that sustains it.”

Largely as a result of the massacre at San Quentin, California’s prison system became more stratified than it had ever been. “When we have a hit, the first thing we try to find out now is not who did it but if the color of the man running was the same as the man who is down,” said Warden Park of San Quentin in a New York Times article published a year after the event.

“If the man down is Black and the man running is Black, we’re all right. But if the man down is Black and the one running was white, then we know we’re in for trouble. We know that we’ll have a killing before the day is over. That’s how it is now.”

What this article doesn’t point out is how correctional officers stoked racial divisions between Black and white inmates, and how, because of this division and the guards’ implicit biases, they positioned themselves in opposition to the Black population. The publication hints at this new reality by pointing out that Black inmates were seen as a “new type of prisoner,” increasingly political, who viewed themselves as “political prisoners,” which bothered the guards.

“It used to be,” the warden explained, “when we got a man, he recognized that he had done something wrong he accepted coming here as punishment. But it’s not that way anymore. Now we get what they call political prisoners. They say that it’s society’s fault that they are here. It doesn’t make any difference whether they were caught robbing or stealing or assaulting someone or what. Nothing makes any difference. They say that they are political prisoners and they have this revolutionary ethic.”

Clearly the warden has a vested interest in the narrative that people who commit crime “belong” in prison; that we should just shut up and do our time. He isn’t concerned with “why” people commit crime, which is inextricably connected to the way in which our society views the role prison plays in it. What he’s not considering is that one can be both guilty of a crime, while at the same time a political prisoner; someone who’s reality is affected in a real way by policies that adversely affect people of color.

This is important to the composition of this piece because it tells the story of the origin of Soledad’s racism. For those who are currently incarcerated here at Soledad in the year 2020, it is clear that the conditions that existed then for Jackson and the broader prisoner class continue to exist today.

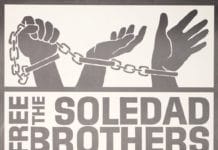

Mention the name George Jackson or Soledad Brothers to Black men in prison, especially here at Soledad, and you will immediately see the reality of the white gaze: Fear, or at the very least, awareness of the ever-watchful eyes and ears of correctional officers who view George Jackson and Soledad Brothers as an omnipresent threat.

I can relate countless stories – and I do, in my soon-to-be released memoir “And Then They Came” – of Black inmates, myself included, who were harassed by correctional officers for simply possessing books written by George Jackson and Angela Davis.

“The California missions were themselves intended as correctional facilities, stations for the recruitment and transformation of the native Indians from heathen hunter-gatherers to Catholic laborers.”

George Jackson and people like him represent a threat to the system. Their critique of capitalist white-supremacy in relation to the prison system is feared because it exposes prison for what it really is: a racist, capitalist enterprise that is criminogenic by nature. George Jackson as we know him didn’t exist before he was sent to Soledad. He was created by the system, and was keenly aware of what he was becoming, as expressed in his writing, like this passage:

“They’ll never count me among the broken men, but I can’t say that I am normal either. I’ve been hungry too long. I’ve gotten angry too often. I’ve been lied to and insulted too many times. They’ve pushed me over the line from which there can be no retreat. I know that they will not be satisfied until they’ve pushed me out of this existence altogether. I’ve been the victim of so many racist attacks that I could never relax again. My reflexes will never be normal again.”

And in explaining the conditions of prison and its treatment of young Black men, he said: “It is such things that explain why California prisons produce more than their share of Bunchy Carters and Eldridge Cleavers.”

Revolutionaries don’t come to prison, they are created by it; and California, Jackson points out, creates more than their share of revolutionaries. This is the ugly reality that California’s Department of Corrections wants to keep secret. They want us to look at themselves as benevolent “peacekeepers,” protecting society from criminals. They don’t want to tell you that they’ve known definitively since studies conducted in the 1960s showed that prisons are, by their very nature, places that produce criminality, which is good for business because it ensures a continuous stream of income – a revolving door of prisoners returning to feed the beast that created them.

Soledad State Prison is rooted in racism and xenophobia that touches every facet of its existence.

Not only were the very materials used to build this prison salvaged from a former Japanese internment camp, later used as a German POW camp, but recently I learned that the very land this prison is built upon is the home of Ohlone natives and their various divisions: the Chalon, Esselen, Yokuts and Salinan, who were slaughtered and forced onto La Mision de Maria Santisima Nuestra Señora de la Soledad (Mission of Mary Most Holy, Our Most Sorrowful Lady of Solitude) for which this city is named. Jessica K. Feinstein wrote in “Soledad, Revisited:”

“It was not an accident that the CTF was built a few miles from the ruins of a mission named for the solitude surrounding it. Isolation, wrote Michel Foucault in ‘Discipline and Punishment,’ ‘is the first disciplinary principle around which the modern prison is organized.’ Alcatraz is surrounded by water; Soledad, by fields. Society thus safely exiles its miscreants. And, in a sense, the California missions were themselves intended as correctional facilities, stations for the recruitment and transformation of the native Indians from heathen hunter-gatherers to Catholic laborers.”

In what seems like a way to remind inmates at Soledad that prison is a thing that “civilizes,” there are two large murals iconizing Spanish colonizers painted on the walls of the dining hall here at Soledad’s central facility. One depicts Spanish conquistadors on horseback making their way through the hills of what would become Soledad, trailed by mercenaries and Catholic priests, all on horseback, carrying a wooden cross, with women (presumed to be colonized natives) walking alongside them.

The other mural depicts the same group of people in a makeshift open-air church, kneeling before the priest. We’re not sure if this is a depiction of Father Fermín Francisco de Lasuén, founder of Mission Soledad, or Father Junipero Serra, because there is no official record of these murals in prison records or online.

However, because of its resemblance, we’re leaning towards this mural’s being a reproduction of a famous painting depicting the arrival of Father Junipero Serra to the Monterey Bay, who immediately upon arriving in 1770 “erected a cross near an oak tree, hung a bell on the limb, began the formal founding of Mission San Carlos Borromeo, the second mission of the province and celebrated its first Mass.” The picture depicts the original location on the shores of Monterey Bay at the Presidio. “It was eventually relocated near the Carmel river, with better access to water and close to a native village.”

When I first walked into the dining hall, before I even knew the history of this prison, I was bothered by these two murals. Firstly, because of the blatant sexism depicted in one, the intended display of superiority through Christian colonial iconography, and the erasure of native culture and existence represented in them both.

Here we are, at a prison that is staffed by a demographic predominantly Hispanic and Latino who, when asked about the mural, have a completely different response than the prison’s Hispanic and Latino inmate population, who view this mural as weaponized artistic expression, one of the most subtle forms of cultural aggression.

These murals were present during the days of George Jackson, and undoubtedly were referenced as a clear example of imperialism. Painted by an unknown artist and dated 1958, these murals are clearly outmoded, but speak volumes about the message the prison is trying to send to those largely descended from indigenous peoples.

There is a petition being drafted as this is being written, and a plan is being formed on how to attack this racist imagery. If the world can see the problem in the presence of confederate monuments of the South – and in fact, there is “Confederate Corner” down the street from this very prison itself, a small town just outside the city of Salinas, which was renamed to “Springtown” to be “respectful and sensitive to the diverse residents of Salinas and Monterey County” – then we must look at these murals as being equally offensive.

Like the confederate monuments of the South, these murals do not represent reality, they attempt to create a narrative that fuels racist ideas that have negative physical consequences which actually harm people of color. These murals must be removed if CDCR is serious about rehabilitation.

Outside of the murals themselves, the refusal to view their continued display as being problematic is indicative of a larger issue present at Soledad and throughout CDCR as a whole: that is, the refusal of correctional officers and officials to change.

Paradoxically, by embracing the ethos of violence, Jackson and his comrades were not defying imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy; unwittingly, they were expressing their allegiance.

The inmate population has made great strides to broaden their perspectives on incarceration, questioning the culture of violence, going to great lengths to challenge it and taking a closer and more in-depth look at personalities such as George Jackson through the lens of Black feminist authors like Bell Hooks.

Hooks, in her book “We Real Cool,” points out the importance of looking at the system holistically, critiquing the way in which race, class, sex and gender intersect in areas such as the prison system, showing that at the very root of so many of our problems is the way in which we define and express masculinity. She points out that:

“In Soledad Brother, with keen insight and sincerity, Jackson reveals the pain and crisis of a young Black male’s struggle to be self-determining, yet his assumption that patriarchal manhood expressed via violence is the answer is tragically naive.”

Hooks speaks of America being rooted in “a culture of imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy” that has a specific way in which it sees the Black male. “At the center of the way Black male selfhood is constructed in white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy,” she writes, “is the image of the brute – untamed, uncivilized, unthinking and unfeeling.”

This is the very justification that was used for slavery and what politicians use today to justify mass incarcerating Blacks and other people of color. Hooks explains that the very foundation of this country, being rooted in imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy, cannot survive without our buying into and portraying the very stereotypes that have been created for us. She points out that the failure to realize this, or, rather, to develop a framework outside of the patriarchal model, was the biggest mistake of the political approach of revolutionaries such as George Jackson. She wrote:

“While the hypermasculine Black male violent beast may have sprung from the pornographic imagination of racist whites, perversely militant anti-racist Black power advocates felt that the Black male would never be respected in this society if he did not cease subjugating himself to whiteness and show his willingness to kill.

“‘Soledad Brother’ a collection of letters written by George Jackson during his prison stay, is full of his urging Black males to show their allegiance to the struggle by their willingness to be violent. Paradoxically, by embracing the ethos of violence, Jackson and his comrades were not defying imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy; unwittingly, they were expressing their allegiance. By becoming violent they no longer have to feel themselves outside the cultural norms.”

To this critique of Jackson, I would add that we can’t forget the time and place that witnessed his existence. The name of the game in those days was “kill or be killed.” Guards needed it that way to maintain control. So, most cases of Black violence and prison violence in general, Jackson points out, are “a forced reaction. A survival adaptation.”

Send our brother some love and light: Talib Williams, V69247, CTF CW-121, P.O. Box 689, Soledad CA 93960. And visit his website, www.talibthestudent.com. Ever since the July 20 3 a.m. raid by guards against more than 200 Black prisoners – only Blacks! – Talib, the main target of the raid, has been punished. The apparent purpose of the raid, in addition to exposing the men to COVID, was to find evidence to “validate” Talib as a “gang” associate, an effort guards have pursued for 10 years so they can isolate him in solitary confinement. They consider him a threat because his father, also in the system, was a member of the Black Panther Party 50 years ago. As the Bay View goes to press, we have learned that Talib has been denied family visits for five years.

Store

Store