by Tara Belcher

In the August 2018 issue of the San Francisco Bay View, Kheven LaGrone wrote an article that addressed the need for California to pass hate crime laws that protect the homeless. I was deeply moved by this article and felt compelled to add my voice to this conversation.

My hope is that others may look within their families, neighborhoods and school rooms with caring eyes and open ears. My hope is that we will stop scoffing at and scorning, neglecting and abusing the homeless when we have the means to lend a hand.

I am from Birmingham, Ala. – the Magic City. I lived in Evergreen Bottom in the early ‘70s through the late ‘80s before moving to the Rosedale Community in Homewood. Finally, prior to my incarceration in the late ‘90s, I moved to West End.

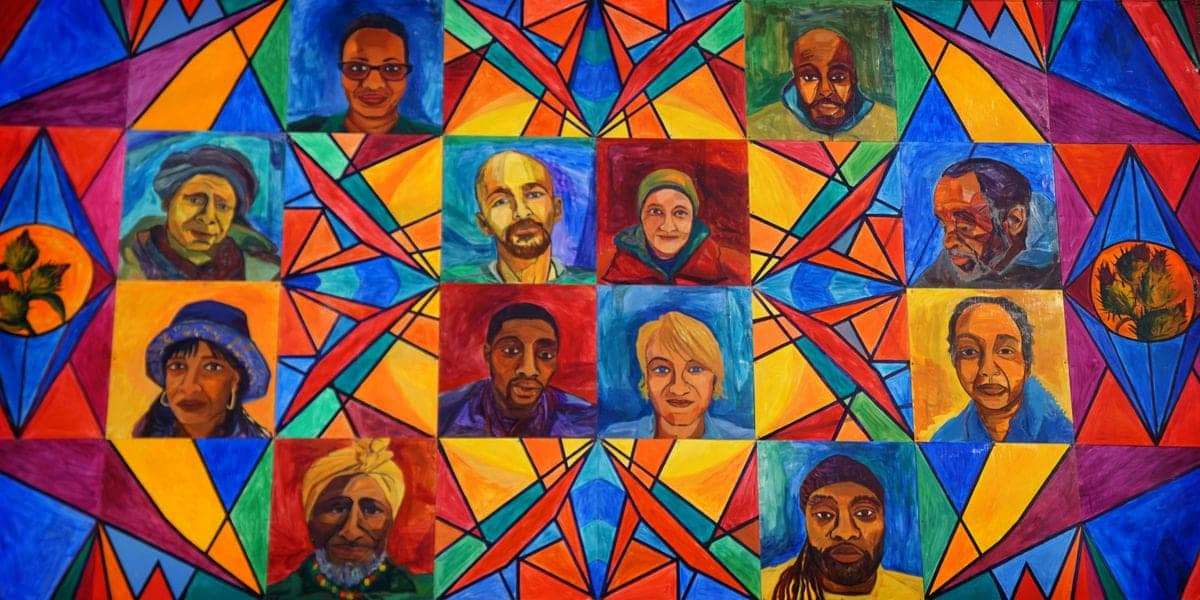

I have never been homeless, but I understand that homelessness has many faces and races. Homeless people come from many places and through all walks of life.

When I lived in Birmingham, the Salvation Army and the Jimmy Hale Mission were the only havens for homeless people in my community. I am sure their resources were limited and couldn’t meet the needs of all who reached out for help.

I am also sure no one chooses to live beneath a bridge or to freeze to death on a porch where a family occupies a home, as Jimmy Shine did.

Growing up, I remember Jimmy quite vividly frequenting the local convenience stores to buy wine and squares, in his own world, a threat to no one. Still, he was treated as a social outcast.

I know that Jimmy wasn’t always homeless. I imagine, at some point in his life, something happened to him – perhaps a psychological breakdown.

But no one in the hood could identify the symptoms or point Jimmy in the direction of help. There was no help.

One cold winter night with nowhere to go and no one to welcome him into their home, Jimmy died.

I am sure no one chooses to live beneath a bridge or to freeze to death on a porch where a family occupies a home, as Jimmy Shine did.

Like Jimmy, countless men, women and children slept beneath the viaducts on Morris Avenue while business and life went on as usual.

At the 26th Street overpass entering I-65, I remember a homeless man who stood on the side of the road with a sign that read, “Will Work for Food.” Each time I saw him, I would stop and give him what I could, never questioning him.

Throughout my time living in Birmingham, I have borne witness to the struggle of many people like Jimmy; I have passed countless sign-holding homeless people; and I have experienced homelessness with people who I love.

When I was young, I had a friend Tiesha, who was a beautiful, full-figured and a fun-loving girl. As children, we’d dance and giggle. As teenagers, she’d flirt with the guys I’d fight off.

She didn’t make good grades. I was in a magnet program. We were different but complimented one another. I was the tough, tomboy type. She was the girl with the inviting hips. We were inseparable.

But when we turned 19, our lives took dramatic turns. In early 1994, I moved to Pascagoula, Miss., for almost two years. When I moved back to Birmingham in late 1995, I asked around about my childhood friend and received so many disheartening, negative reports from folks.

I would always defend Tiesha and retort that something must’ve happened to her. It was rumored that someone slipped a hallucinogen into her drink, she took a bad trip and never returned.

When I was living in West End, I would often take the Arkadelphia Road exit to visit my parents in the Bottom. One day after work, I decided to take the long way and go through Smithfield for some reason. I’ll never forget.

As I approached Smithfield Library’s traffic light, I saw a woman darting through traffic trying to stop commuters unsuccessfully. As the light turned red, I sat and got a clear view of the woman’s face. It was Tiesha.

I rolled down the window and bellowed for her to come to me. Without hesitation, she entered the passenger side of my car and sat. The description that folks had given of her appearance was accurate. But that didn’t matter to me. She was my friend.

She only wanted a dollar and to get out at the next corner. I gave her $10 and wished her well. That was the last time I saw Tiesha. I trust that she’s still among the living, somewhere.

“Tiesha, it’s Tara,” I recall saying, “Don’t you remember?” She had a blank look on her face and it was clear she didn’t recognize me. Daring myself not to breakdown in front of her, I asked if she needed anything and if there was anywhere in particular she wanted me to take her.

She only wanted a dollar and to get out at the next corner. I gave her $10 and wished her well. That was the last time I saw Tiesha. I trust that she’s still among the living, somewhere.

Homeless people are constantly stigmatized, stereotyped and criticized. They are misunderstood and under-represented.

Veterans suffering from PTSD who lose hope in god, love, property – they never imagined homelessness would be in their future. But upon return from war, they’re failed by the country they served and they struggle to get the financial, social and emotional support they deserve.

A young Black girl traumatized by poverty living in a community devastated by drugs, Tiesha never got the opportunity to realize her potential. She never stood a chance against the systemic and structural barriers that define life for people of color in this country.

A young Black boy, who lost his mother to incarceration. A sweet, innocent boy. A smart, resourceful, ambitious young man. My son.

When I was first incarcerated, for years I would donate to a mission that helped provide meals, shelter and other services to homeless people. I never imagined that one day my own son would be homeless.

In 2008, I reconnected with my son’s estranged father. We hadn’t had any contact since 1998, prior to my incarceration. But I knew my son needed his father, so I hired an attorney to locate him.

Muriel, my son, had just turned 19 years old and was driven, goal-oriented and gifted. He worked in the culinary arts industry for a highly regarded restaurant. He also enlisted in the Navy.

I was proud of my baby and wanted to support him in any way I could. He was being discharged from the custody of the Department of Human Resources and his social worker brought him to see me.

He was the most beautiful, healthy, strong, poised, confident, ambitious, intelligent, articulate young Black man. I was so proud of him. My only child.

Eventually I wrote Muriel’s father, but he never replied to me directly. Still, he didn’t hesitate to reconnect with our son.

Muriel wrote a 10-page letter telling me the story of how his father came to get him and took him to a family gathering where he got to know his father’s side of the family. He wrote that he met his nine other siblings and spoke of how he and his uncles clicked off the top.

I felt very blessed and grateful that my baby would no longer be alone in the world.

In April 2008, Muriel was scheduled to re-take his enlistment exam because he’d failed his first exam by four points. I had arranged for him to have access to financial support should he ever need it. He was good to go.

Seeing him this way broke something in my spirit and, to this date, my heart bleeds for my baby. Muriel had lost all hope and drive to live.

Then something happened. Muriel disappeared for two and a half years.

Family hadn’t heard from him. I began to fear the worst and in December 2010, I filed a missing person’s report with the Birmingham Police Department.

The police chief wrote to inform me that Muriel had filed a missing property report in the previous year. Every time I picked up the local paper, I feared I would come across a heartbreaking story with his name in it.

Muriel’s former social worker maintained contact with me. He couldn’t make any sense of Muriel’s strange behavior but assured me it wasn’t drugs.

Finally, in 2011, I got an unexpected letter from my baby. He was living at the Salvation Army. It was during the season of storms that wreaked havoc on downtown Birmingham and beyond.

I didn’t hear from Muriel again until 2013, when he wrote to let me know that he was living at Birmingham Healthcare for the Homeless.

I had been told by social workers here at the prison, who were in contact with Muriel’s new social worker, that he suffered from mental illness, but they couldn’t disclose any more information to me. I felt and still feel helpless as a mother.

In August 2013, I finally saw my baby for the first time since 2008. I didn’t recognize him. It was clear that his mental health had rapidly declined. It felt like he had taken on a new identity.

Seeing him this way broke something in my spirit and, to this date, my heart bleeds for my baby. Muriel had lost all hope and drive to live. He didn’t relate to anything we had talked about before – my baby had checked out.

In 2016, I was informed by Muriel’s former social worker at the Department of Human Resources that he’d seen Muriel on occasion walking downtown – clearly homeless – sometimes with someone, sometimes alone.

Send our sister some love and light: Tara Belcher, 00211, Tutwiler Prison, 8966 US Hwy 231 N, Wetumpka, AL 36092.