by Susie Day

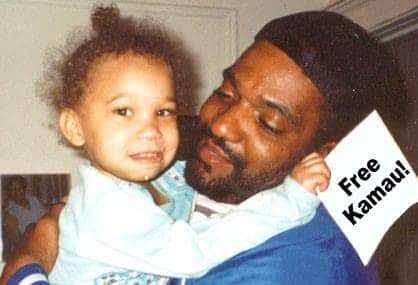

“As we left the courtroom, [a friend] was standing in the hallway with K’Sisay, Kamau’s 2-year-old daughter. As Kamau walked near her, she held out her arms to him. Kamau took two steps toward her and the marshals jumped him and began beating him … I will never forget the haunting scream of that child as she watched her father being brutally beaten.” – Assata Shakur, “Assata: An Autobiography”

That 2-year-old, K’Sisay Sadiki, is now in her 40s, with kids of her own. She has lived her life in two worlds. She’s attended prestigious dance and film schools, holds down a steady job, pays taxes. And, as the child of Black Panthers, she’s lived underground, raised by people dedicated to overturning white supremacy.

Her father, Kamau Sadiki, also has a daughter – K’Sisay’s sister – by Assata Shakur, who famously escaped from prison in 1979 and now lives in Cuba as a “dangerous fugitive,” hunted by the US government. Kamau is in a Georgia prison, serving a life-plus-10-years sentence for the 1971 fatal shooting of a police officer – a cold case, resurrected in the post-9/11 world.

K’Sisay tells me about how she’s making sense of her life. “I need people to know who my parents are. Who I am, too, as a woman who has lived in the background, not feeling comfortable with sharing my father’s story.”

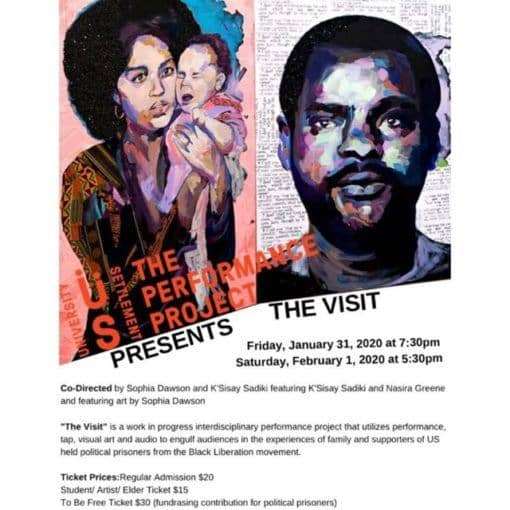

On Jan. 31 and Feb. 1, she performed “The Visit,” her one-person show, at University Settlement in Lower Manhattan. Part of an installation by the artist Sophia Dawson, “The Visit” is K’Sisay’s work in progress, an exploration of her double reality – and a way to educate people about her father.

K’Sisay: I was born into activism. Both my parents were Black Panthers in the Queens branch of the party. When I was a baby, my father was arrested for a robbery and served five years in prison. He wrote me letters, like, “Oh, my baby’s sick. When I get out, I’m going to be there for you.”

My mom and I would visit my father when I was a toddler. Once we went to visit; my mom said he’d gotten his GED. So I thought we were there to celebrate something. They put my mother and me in a room and said he’d be out soon. But he didn’t come.

My mother and I were there for hours, so long that I peed on myself and started screaming. Then they brought my father in. My mother didn’t want him to react with anger: “This is my family – look what you did to them!”

She tried to calm him down, calm me down, make the best of the situation. My mom would always try to make things brighter. She’d pack picnic lunches. “We’re going to see your father. Then we’re going to the lake!”

But there are photographs of me as a little girl, and you can see the stress. Going to court and stuff, I experienced trauma. My grandmother told my mother, “You can’t expose her to that. You have to make a decision.”

So I was also raised going to art camps, being exposed to theater, knowing my family wanted the best for me: “Whatever your dreams are, let’s cultivate them.”

Susie: Is there a similarity between you as a Panther kid and kids growing up in the 1950s Red Scare, whose parents were Communists?

K’Sisay: Yeah, we definitely couldn’t say certain things and we were taught a code. At school, I never stood up to say the Pledge of Allegiance. That was something my mom taught me as a little girl.

I went to a predominantly white school in Queens, and I thought, “Damn. Why are these teachers so mean to me?” Like they loved their little white girls, but they hated me. Then there was me not standing up to say the pledge.

My mother was comrades with this other woman from the Panthers. Her daughter and I were raised together. They would dress us up and take us to Broadway plays and stuff, and we’d wear these little pink dresses or whatever. They just liked dressing us up.

But I was raised around kids of Panthers and taught that we were blood cousins. It was like, OK, we know we’re different.

Susie: Your father got out of prison in 1979. In an earlier version of your show, you talked about him training you as a kid in Panther drills and calisthenics.

K’Sisay: It’s funny, my father did want me to be this soldier. But my mom said, “This is a little girl. She likes dancing school. Your approach has to be different.”

Susie: Your dad was released about the time Assata escaped and went underground.

K’Sisay: I barely knew that; my mom and dad kept some things from me. I didn’t know that my parents were being threatened. The FBI was telling my mom, “We’re going to kidnap your daughter.” I had no idea. I lived through a child’s lens.

My mom did have a room where she kept old Panther newspapers and articles. I would look at them but they made me afraid.

Susie: A few years later, from Cuba, Assata published her autobiography. In it she wrote about your dad – and you.

K’Sisay: A lot of my friends on the block read Assata’s book. They said, “K’Sisay, how come you didn’t tell me you’re related? What’s your story?” I’d say, “I don’t want to talk about that.” Because I felt shame. Yeah, I felt like I was living two lives.

Susie: Tell me about your dad.

K’Sisay: He worked for the telephone company. He was a man of the community. He loves storytelling and reading, especially science fiction, parallel worlds and stuff.

He used to show up in his truck and gather the kids around him, “Come on, everybody!” And he’d tell the kids these stories. They were all [mimes amazement] “WOW!” He exposed me to Octavia Butler, like “Wild Seed”: “K’Sisay! I got this book.”

I moved to Brooklyn in fourth grade, but my father and I always lived close. He and my mother could never live together but he always lived in the neighborhood. I had a key. He just liked life simple. He loved his books. He’d be into Apple gadgets, the latest stereo system.

Susie: So, you grew up, went to school, got a job, got married, had kids. You’re in your 30s, and suddenly in 2002 your father is arrested for child abuse. Then he’s charged with the 1971 killing of a police officer.

K’Sisay: By now, he’s a grandfather, thinking about retiring. I couldn’t believe this was happening. To see my father in the newspapers – humiliated that way. Even for people who support the Panthers, to question whether that was true. I think that the woman he’d been seeing set him up.

Susie: The molestation charge didn’t stick, but it must have made it hard for people to support his case. Your dad was convicted in 2003 of the shooting.

K’Sisay: Even though they had no direct evidence. They tried to get him to turn Assata in, but of course he wouldn’t. I went to see him at court in Brooklyn.

My dad kept looking at me so very apologetic. He just put his head down, like, “I’m so sorry this is happening.” The kids, we were all there. Then my mom and I went to see him at the Brooklyn House of Detention.

I had not been in that situation for years, going through security, being patted down. I never got to see him again in New York. It was more devastating for me as an adult to see him in prison than it was when I was a child. I was in denial. That took years to deal with.

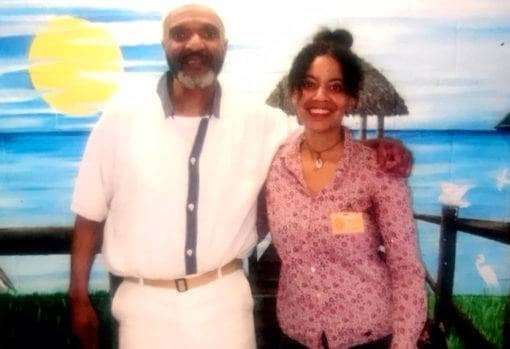

Susie: Your dad is now turning 67 at the Augusta Medical State Facility in Georgia. Tell me about your last visit.

K’Sisay: I visited him last summer. It was wonderful to see him. But he has serious health issues and the conditions there are horrible.

Susie: What, above everything, have you learned from your father?

K’Sisay: Strength. Humility. He’s my hero. He made a commitment to deal with injustice. He was that person even before he joined the Black Panther Party.

I couldn’t always talk about this. I’ve been silent for a long time. Now, I am his voice. I may not be able to physically see him, but he’s with me always. I dream about him and he’s free – I never dream about him in prison.

OK, he’s free – but he’s WANTED. [Laughs]. I’m always looking for an Underground Railroad. “Come on, Daddy, we can go here!”

But he’s always free.

Susie Day writes about prison, policing and political activism and is a columnist for New York’s Gay City News. Her book “The Brother You Choose: Paul Coates and Eddie Conway Talk About Life, Politics, and The Revolution” was published in 2020. Email her at susie@monthlyreview.org.

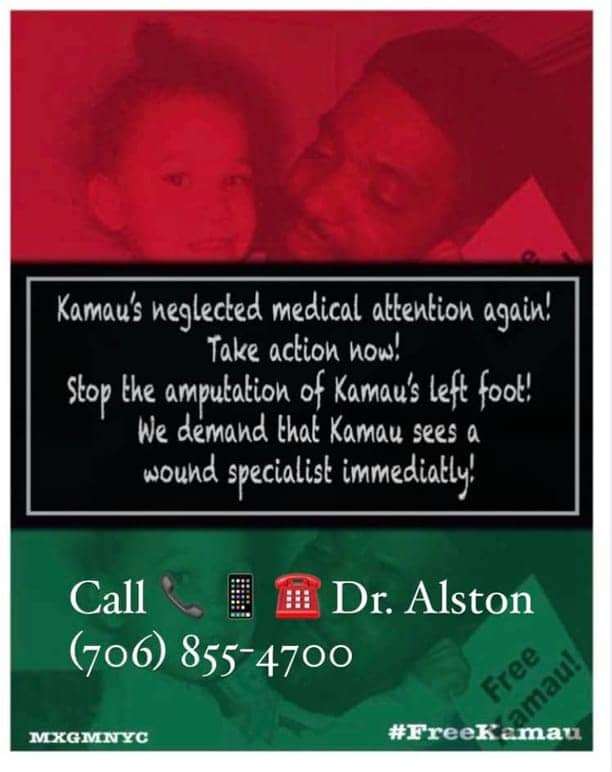

Urgent medical action is needed for veteran Black Panther political prisoner Kamau Sadiki!

Despite the fact that Kamau’s name was legally changed from “Freddie Hilton” and despite the fact that the prison has sarcastically stated to some callers that, “He seems to be a real popular guy with all the calls that have come in,” prison officials have sought once again to continue their plan to both medically neglect and ignore Kamau’s request for a wound specialist.

“He needs a wounds specialist – not amputation!”

Augusta State Prison officials instead plan to cut off his foot, potentially killing him when you consider his other serious medical condition of Hepatitis C and the ongoing threat of COVID-19 throughout the entire U.S. prison system.

So, when calling the prison about his extreme medical emergency, please use his government name, “Freddie Hilton,” and his Georgia prisoner ID No. 1150688.

From Kamau’s daughter K’Sisay Sadiki

“Call now! Freddie Hilton aka Kamau Sadiki, No. 1150688: ASMP wants to amputate my father’s foot at the ankle.

“Write: Augusta State Prison, 3001 Gordon Hwy, Grovetown GA 30813. Call: Chief Medical Facilitator Dr. Mary Alston and Warden Ted Philbin (706) 855-4700.

“He needs a wounds specialist – not amputation!”

Who is Kamau Sadiki?

Kamau Sadiki is a veteran of the original Black Panther Party. At the age of 17, he dedicated his life to the service of his people. He worked out of the Jamaica, Queens, office of the Black Panther Party. Having internalized the 10-Point Program and Platform, the Three Main Rules of Discipline and Eight Points of Attention, Kamau used his knowledge to guide his organizing efforts within the Black Community.

Kamau worked in the Free Breakfast Program, getting up every morning, going to his designated assignment and cooking and feeding hungry children before they went to school. When the Free Breakfast Program was over for the day, he reported to the office, gathered his papers, received his assignment and went out into the community to sell his papers.

While selling papers, Kamau continued to educate the people – all while organizing tenants, welfare mothers and whomever he came in contact with. At the end of the day, he reported to the office. He wrote his daily report and attended political education classes.

Kamau Sadiki was one of the thousands of young Black men and women who made up the Black Panther Party. The rank-and-file members of the party made the Black Panther Party the international political machine it was.

While the media followed Huey Newton, Bobby Seale and others, the day-to-day work of the party was being carried out by these rank-and-file brothers and sisters, the backbone of the Black Panther Party.

They were these nameless, faceless, tireless workers who carried out the programs of the Black Panther Party, without whom there would have been no one to do the work of the Free Health Clinics, Free Clothing Drive, Liberation Schools and Free Breakfast for Children Program. It was to these brothers and sisters to whom the people in the Black community looked when they needed help and support.

COunterINTELligencePROgram

It was because of this tireless work in the community that then-FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover declared the Black Panther Party to be the greatest threat to national security and sought to destroy it. It was not because we advocated the use of the gun that made the Black Panther Party the threat: It was because of the politics that guided the gun.

An all-out propaganda war was waged on the Black Panther Party. Simultaneously, a psychological and military campaign was instituted.

We had been taught that politics guide the gun, therefore our politics had to be correct and constantly evolving. We had to study and read the newspapers to keep abreast of the constantly changing political situation.

But this was not the image that the government wanted to portray of the Black Panther Party. It preferred the image of the ruthless, gangster, racist gun-toting thug. Every opportunity that came up to talk or write about the Black Panther Party was used to portray this image.

When the opportunity didn’t arise on its own, they created situations and circumstances to make the claim. An all-out propaganda war was waged on the Black Panther Party. Simultaneously, a psychological and military campaign was instituted.

The government’s war of terror against the Black Panther Party saw over 28 young Black men and women of the Black Panther Party killed over a period of less than four years, hundreds more in prison or underground, dozens in exile and the Black Panther Party in disarray. Even though the Black Panther Party as an entity had been destroyed, the government never ceased observing those Panthers who were still alive.

Whether or not others believed it, the government took seriously that aspect of the Black Panther Party’s teaching that included the 10-10-10 Program. If one Panther organized 10 people, those 10 people organized 10 people and those 10 people organized 10 people – exponentially, we would organize the world for revolution. The only way to stop that was to weed out the Panthers.

Not only must the Black Panther Party be destroyed, but all the people who were exposed to the teachings must be weeded out and put on ice or destroyed.

During this turbulent time, Kamau was among the members of the party who had gone underground. He was subsequently captured and spent five years in prison. While he was on parole, he legally changed his name from Fred Hilton to Kamau Sadiki.