by Ed Mead

There had been a bit of a prisoners’ moment back in the 1950s; it took the form of a rash of prison riots across the country. As a result of this national uprising, changes were implemented, wardens became superintendents, guards became correctional officers, prisoners became inmates and the prisons themselves were renamed “correctional institutions.”

Only the names had changed, everything else stayed pretty much the same. The era of rehabilitation had arrived. The nation’s prisoners were again quiet.

Next, prisoners tried to use the courts to bring about change. Up until the late 1960s the courts had what they called the “hands-off” doctrine when it came to prisoners. The line was a lot like the Supreme Court’s 1857 Dred Scott decision, which held that Black people, as property, had no rights the white man was bound to respect.

The same was true when it came to prisoners: No matter how bad the atrocity, the courts almost always refused to intervene – citing the hands-off doctrine as a justification for their failure to act.

Then came the early 1970s and with it the development of a national movement of prisoners. It was led by revolutionary Black convicts, and white prisoners joined them. Jailhouse lawyers bashed down the hands-off doctrine and the courts were making all sorts of rulings in support of the rights of prisoners.

One such case, Procunier v. Martinez, 416 U.S. 396 (1974), substantially expanded the First Amendment right of prisoners to send and receive written materials to and from the outside world. Prisoners on the East Coast, West Coast and Midwest were publishing newspapers speaking to the world and to each other.

This movement culminated in the Attica Massacre, in which 47 prisoners and guards were murdered by New York state police. One of the Attica demands was for transportation to a non-imperialist country.

The following repression took many forms, one of which was then-President Ronald Reagan. This included long-term SHU placement, out-of-state transfers and even the cooptation of some of the progressive prisoners.

As soon as the political aspect of the movement was brought under control, the courts rolled back the advances prisoners had made on the judicial front. For example, Turner v. Safley, 482 U.S. 78 (1987) and its progeny gutted Procunier and have almost rolled the rights of prisoners back to the “hands-off” days.

There are several important lessons here. The first is that for prisoners to get anywhere they must have an organized national presence. At this point, that presence is the united front called Prison Lives Matter (PLM).

If you consider yourself to be a person who loves freedom, then your duty is to become a part of this movement. Yes, it will require struggle and sacrifice. And you will need to abandon your “me first” (FTW) attitude.

Secondly – here I speak for myself and from my own experiences and not for PLM – there must be no more Attica rebellions – only the peaceful and responsible withholding of all prison-related labor for extended periods of time. It takes a very long time for outside supporters to come into play – months.

The first two demands should be to extend freedom and democracy by insisting on the right to vote and to end the practice of constitutionally sanctioned slavery. Yes, we know it will take a long time to win these two demands, although merely listing them raises public awareness to the point that these demands can be won later.

There was a historic series of hunger strikes in California that started in July 2013. According to the California DOC, the first strike involved over 6,600 prisoners and ended only after promises were made by the state.

The hunger strike leaders included representatives from every gang and they issued a statement that effectively if not completely ended gang violence on the inside.

The second hunger strike involved nearly 12,000 prisoners – again, DOC figures – and lasted until promises were made with guarantees. The third strike involved 30,000 prisoners not eating and 2,600 more refusing to work – DOC figures given to the press.

This time, the strike ended with guarantees from the federal court. How that has worked out depends on who you ask. In my opinion, not much really changed. The leaders were released from one hole only to be placed in another hole with a different name.

Don’t get me wrong, the California hunger strike was a great political accomplishment. The leaders included representatives from every gang. They issued a statement that effectively if not completely ended gang violence on the inside.

Moreover, they demonstrated what could be accomplished with unity. They were on the ground and knew what could or could not be accomplished with the strength they had. I was not there and do not have that knowledge.

Yet in my opinion, even with the state’s news media supporting them and a vibrant statewide outside support network, the prisoners failed to reach for the brass ring.

Back then, I was the publisher of the nation’s largest prison newspaper, Prison Focus, and an avid supporter of the strike. I editorialized that prisoners should not trust the courts, as what they give today they will take tomorrow. I urged them to form a statewide organization that would last beyond the current struggle. I was ignored.

Today we are on the cusp of a new national prisoners’ movement in the form of PLM. I am asking you to do what I did a long time ago. In the late 1960s I timidly stuck a single toe into the revolutionary waters of the day. Today I’m a 79-year-old communist revolutionary. May your life also be as meaningful and interesting. Please, become a part of PLM and help grow our movement.

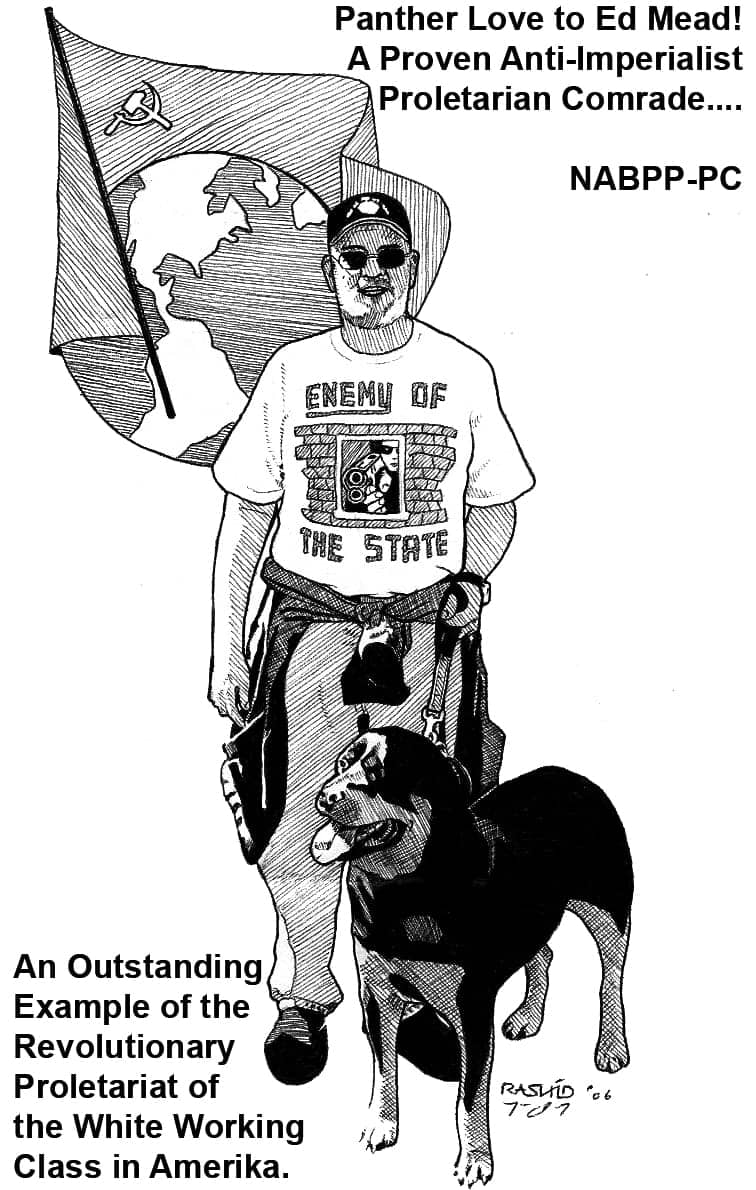

Ed Mead has been a prison activist and revolutionary communist since the 1960s and was formerly publisher of Prison Focus newspaper. His book “Lumpen: The Autobiography of Ed Mead” came out in 2015.