Honoring George Jackson’s birthday on Sept. 23

Wanda: It was wonderful seeing you this past weekend at the Black August event in Oakland. I’m really happy you’re joining us to talk about Black August.

Kumasi: I grew up at a time in the 1950s where my generation watched every country on the continent of Africa wage independent struggles and anti-colonial struggles, and we saw them one by one – pulled the foreign flags down, raised their national flags, began the process of rewriting their own history and trying to reconstitute their own civil societies, with South Africa being the last frontier.

No one thought that the South Africans – because Britain had nuclear power and their chief supporters were the United States and the Israelis, with the power and the might that they had – no one believed that they would ever make a concession and allow the South Africans to govern themselves.

They didn’t believe it would ever come to the point of free elections, where they would be able to elect their own people from their own ethnic groups within that country and start the process of rebuilding their country. It never, and still has not, gotten where it should be. But the process is already begun. We never thought they could get as far as they have today.

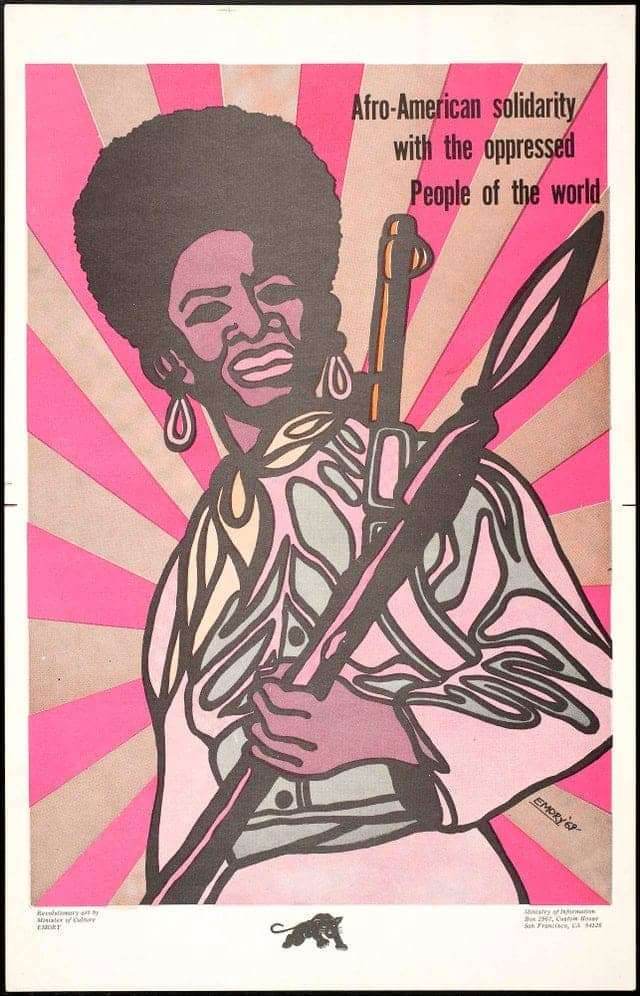

So, watching the Cuban Revolution and its success – all of these things were an inspiration to us. All of these things and these people around the world who dared to struggle, who dared to win – that was what convinced us that a successful revolution in this country was possible, that a Black revolutionary could take up the fight and follow the path of other revolutionaries around the world, and we actually linked ourselves with them in solidarity. Every time that there would be an independence celebration, we would have representatives there to voice our solidarity with them.

These were the things that shaped our minds, shaped our attitudes and convinced us that what we were doing, in spite of the fact we were going to suffer great losses and make great sacrifices, that we were going forward. We wanted to keep moving forward – there was going to be a time, we understood, where there was going to be a period of inactivity, a lull period.

People were going to, at some stage, think that they had been defeated, and lie down and do nothing. But somewhere, sometimes – not knowing what would be the spark that would ignite the fire again – these fires would rise, people would rise, the momentum would come back and we would have another movement again. Our people would move forward again. No matter how many times we would be stopped, we would always get started again until we arrived at the place intended and we got what we wanted out of these struggles.

How do people, throughout history, from the beginning of time, who found themselves in our position – what have they done to relieve themselves of the circumstances that left them in a position where they were just floor mat of the world?

So, that was the way I was shaped, this is the way I was groomed, this is how I saw things unfolding. And this is why today, when we have the Black August events, it is not a celebration of any sort – it is a commemoration.

It is a commemoration of the people who inside of the prison movement had lost their lives fighting – not only for prisoners’ freedoms, but also fighting for the freedoms of people outside of prison. Our struggles inside of prison had never been disconnected from the overall concerns and struggles and issues surrounding our people and our history in this country.

What made it unusual is the fact that: Here are people who had been put in prison for a criminal offense. And you would say, “Well, most of these people in some way or another have attacked the community from which they came. How is it possible they have prepared to give their lives to defend that same community? How is it possible that now they have made a turnaround and decided that when they do get out – if they get out – they’re going to come out with a plan to reinvest themselves in that community, to become an asset rather than a liability?”

It is because we examine history. We raise the question: “Are we free or not? If we’re not free, what are we? Are we slaves? Are we colonial subjects? What is our status in this world, and especially in this country?”

So, the other thing we did was we raised the question: “Where did the crimes of the oppressed begin?” And our analysis was that the crimes of the oppressed begin with oppression itself – had we not been kidnapped and brought to a country, thrown out into this situation without our own consent, without being able to express our own desires and intent.

We were put into a condition where we were left desperate. When you put people in a desperate situation, they’re eventually going to act like desperados. And in the practice of acting like desperados, they’re going to come in conflict with those who control their circumstances through legal measures. And they call this the law and say that you’re in violation.

So, they have a responsibility to deal with you, one way or the other. They’re either going to lock you up, or they’re going to kill you – they’re going to do everything they can to suppress you. Most of the time, putting you in chains and locking you up and benefitting from your being locked up is the easiest way that they can handle that kind of situation.

So, we had to spend a lot of years studying law, studying government, studying history and trying to figure out where do we place ourselves or where have we been placed in the middle of all of this. And we say, well, if we’re not free people, how do we gain our freedom?

That led to the discussion and the study and the research of: How do people, throughout history, from the beginning of time, who found themselves in our position – what have they done to relieve themselves of the circumstances that left them in a position where they were just floor mat of the world? How did they stand up? How did they get up? How did they throw off the chains of slavery and captivity and detention and pacification?

How did they get rid of these? They had to wage struggles. From Spartacus on – they had to wage a struggle, a war of independence or a revolutionary war. The difference between a war of independence and a revolutionary war primarily is the kind of politics that you are going to use so that you can call your struggle a just struggle – the kind of politics you want to insert among yourselves and the people within your movement, so that when you do succeed and you build what you think is a new and better society, you have to have the principles of government.

You have to have the kind of principles of law that will allow you to establish a compatible relationship among the members of the new society and between the members of that society and the administration of that society.

We had to actually change ourselves. You cannot try to come and build and fight for a new and better world if you haven’t created, within your ranks, a new and better man and woman. So that was the biggest thing we did was make that character transformation while we were in prison. You will hear people coming out of prison movement talking about the “new man,” who came in as a criminal and now has become a political person, has become a revolutionary. So he went from a criminal mentality to a revolutionary mentality.

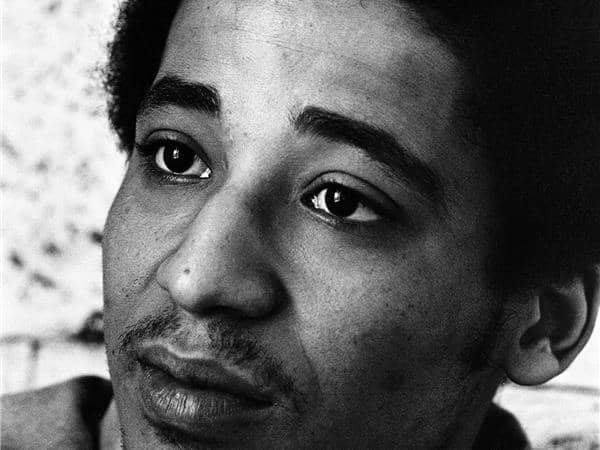

Black August in 1979 was conceived by brothers who were in the Adjustment Center in San Quentin who realized that they had taken some real heavy hits with the loss of George Jackson’s life on Aug. 21, 1971, with the loss of Jonathan Jackson’s life on Aug. 7, 1970, as well as Bill Christmas and James McLain and the wounding, capture and recapture and lifelong experience of torture that Ruchell Magee, the only survivor from the Aug. 7 movement, has endured for all these years.

Ruchell’s got in, what, 51, 52 years now? And if he does leave the California prison system, Louisiana still has some kind of a hold on him. They have filed something against him, saying that if he gets released in California, they want to take him in and put him in prison for the rest of his life.

That’s where he was released from – Angola – and they took his land, his property that he and his family owned and told him he had to leave Louisiana. He came to California, but one of the stipulations was that he had to stay out of jail in California because if he got locked up in California, whatever California was doing, Louisiana was going to take him back in.

Khatari Golden also died in San Quentin. And Khatari was a great leader. He was the greatest. And he made some very serious sacrifices. Khatari told me that he had a date and was getting ready to go home – he was in Chino – when Martin Luther King was assassinated. He saw all this activity on the news, he saw cities in flames all over the country. There were – you know, I don’t want to call them riots, I want to call them rebellions – all over the country and in all the major cities.

He thought – from his point of view and his perspective – he actually thought this was it. This was the revolution. So, rather than him waiting for weeks to be let out legally, he ran away from Chino. He escaped. He told me how he was out in some field and went to sleep, pulled a jacket over him and woke up in the morning with a rattlesnake curled up on his chest. He rolled out from under the jacket real fast. I think a farmer and somebody picked him up in a truck on one of the roads between Chino and LA and gave him a ride.

Somehow he made it all the way to San Diego. And he runs and tells the guys he grew up with, he said: “Come on man, the revolutionary war is on,” he said. “They killed King and look what’s going on all over the country.”

He tries to rally the troops and they tell him: “Hey man, Martin Luther King was the most peaceful brother in this country. You see what they did to him. We’re not going to do anything! What do you think they would do to us? They killed him and he was about nonviolence.”

Khatari leaves San Diego and he goes back to the South where he was born – I don’t know whether it was Louisiana or Arkansas – but he tries the same thing there. And the brothers down there tell him the same thing. So he gets captured because some guy that was his childhood friend, that used to play hide-and-go-seek with him, had become a policeman, and knew all the places that he hid in when they were children and was able to secure his capture.

Within an hour or two of the time limit before the expiration of the extradition order against him, they brought him back and he winds up dying in San Quentin, spends the rest of his life inside the penitentiary. He actually died in San Quentin.

But he didn’t just die in San Quentin. He was in the Adjustment Center, and they were playing football, tag football or something out on the yard. Somehow, he ran into the wall, collapsed, bleeding out of his ears. They deliberately allowed him to die before he was able to get any adequate medical attention.

And as a result, I had a clipping that said that the chief medical officer in San Quentin was last seen being escorted from across the California-Nevada border by the FBI and the Department of Corrections police because there had been death threats against the chief medical officer’s life because he was responsible for allowing Khatari to die.

They created an entire Black August routine that was aimed at getting people to take themselves seriously, to not antagonize or play with each other – to make it a solemn month, a month in which fasting was involved, study was involved, training or discipline was involved.

Well, that happened in August. So that’s why in the month of August we should be further examining events throughout history. Nat Turner started his rebellion in August of 1931 – Aug. 21, 1931, as a matter of fact. Then we look at the whole series of major events – struggles and even losses in the month of August for the last several hundred years.

That was how the Black August calendar was developed, where people would associate the month of August with all these different events throughout our history, events that surrounded our struggle for freedom and the consequences for being involved in that struggle.

This is why they came up with the term Black August. They came up with an entire routine that was aimed at getting people to take themselves seriously, to not antagonize or play with each other – to make it a solemn month, a month in which fasting was involved, study was involved, training or discipline was involved.

But mainly – trying to create a sense of unity. To pull people together, to unite people, to get them to put aside their differences and to understand that they’re all involved in the same situation and that they should work together to alleviate whatever problems, pain, difficulties they face in life so they can move forward and live a life that is qualitative and has some length to it.

Wanda: I was thinking when you talk about looking at this month of August as being a month where it’s a commemorative one but it’s also inspiring with regards to revolutions and revolutionary movements that started – like, besides Nat Turner’s rebellion, the Haitian revolution started with that meeting on the mountain in August. And Marcus Garvey was born in August, his birthday is Friday, Aug. 17, and Harriet Tubman was also born this month.

Kumasi: Aug. 7, 18-something, was the date that Simón Bolívar routed the Spanish for the first time in South America. I call him the George Washington of South America, the liberator of South America. He had spoken with Alexandre Pétion, who was the head of Haiti, and explained to him he was getting ready to go to Spain to visit his father’s people.

Pétion told him: “Well, they’re going to treat you like a stepchild. They’re not going to recognize you.” Bolívar says, “Why?” He says: “Because you’re Creole. You were born away from home; they’re not going to accept you as a member of the family. You’ve got to remember your father came from Spain to a new world, and the Spanish mainly brought the men with them. They met women over here and they made children with them. So, the question is: Where is your inheritance, right? His children in Spain are not going to share any inheritance with you, they’re not going to recognize you as a full-fledged member of the family. They’re going to treat you like a dog.”

So Bolívar went over there anyway. He came back and he said, “You were right. They treated me like a dog and as a result I’m going to chase every last one of them out of South America.” Pétion said: “I’ll give you guns, ships and I’ll give you soldiers if you promise me one thing.” Bolívar said, “What is that?”

Pétion said: “That when you do chase him out and you do create your own government, that when you put together your Constitution, the first law of your Constitution should be an anti-slavery law. And Simón Bolívar told him, “That I will do.” And that’s what he did.

You know, one of the heaviest blows that has been dealt to us is that we still have this identity complex and we don’t know who we are, what we are, and we don’t know which side of the argument to be on. So, you know, many of us are always on the oppressive side – primarily we’re like a dummy, sitting on a ventriloquist’s knee with his hand stuck up. We’re opening closing our mouth, but every time we speak, his voice comes out; his opinions come out, ‘cause we’ve lost ours.

Bay View Arts and Culture Editor Wanda Sabir can be reached at wanda@wandaspicks.com. Visit her website at www.wandaspicks.com throughout the month for updates to Wanda’s Picks, her blog, photos and Wanda’s Picks Radio. Her shows are streamed live Wednesdays and Fridays at 8 a.m., can be heard by phone at 347-237-4610 and are archived at http://www.blogtalkradio.com/wandas-picks.