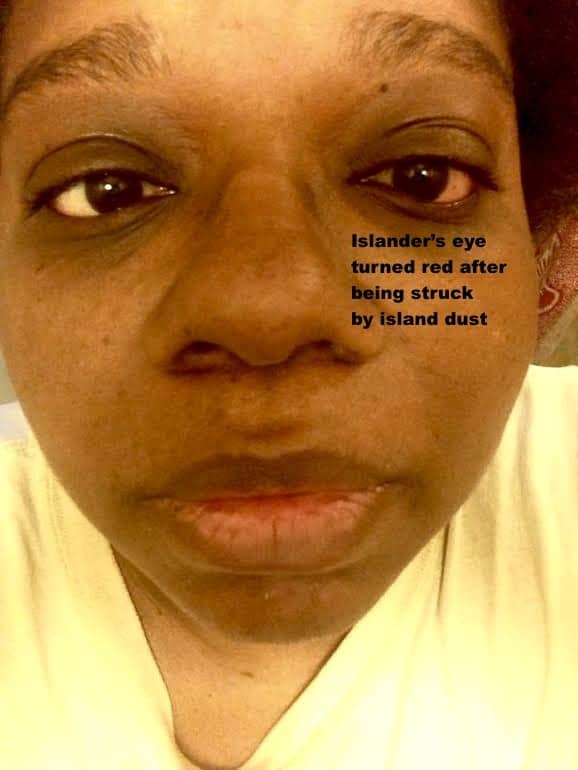

Struck in the eyes

by Carol Harvey

On March 24, 2021, high winds drove sparkling blue waves racing toward the Treasure Island shore. A resident traveled in their wheelchair down pretty, tree lined Gateview Avenue with a friend and their dog.

After a brief hospitalization the previous week, they needed a quiet outing. However, the trip was anything but relaxing. They and many of their neighbors have developed respiratory problems breathing the gritty island wind.

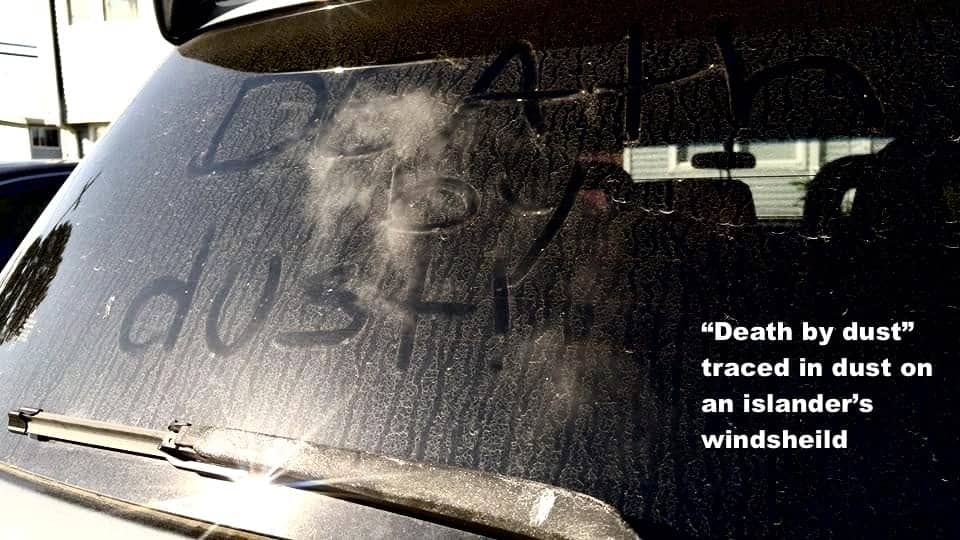

Every day, islanders wipe fine powder from surfaces in their homes and off the windshields of their cars. Dust blows constantly from uncovered soil piles. Tattered tarps on fences don’t block construction dust.

Trucks haul cubic tons of dirt through streets to be dumped at the front of the island. Grading equipment lifts dust in the air over a huge construction zone where condos are being built on the side of the island facing San Francisco across the Bay.

The brown haze is thickened by radioactive particles kicked up by Navy techs unburying toxic waste from radiation and chemical cleanup sites.

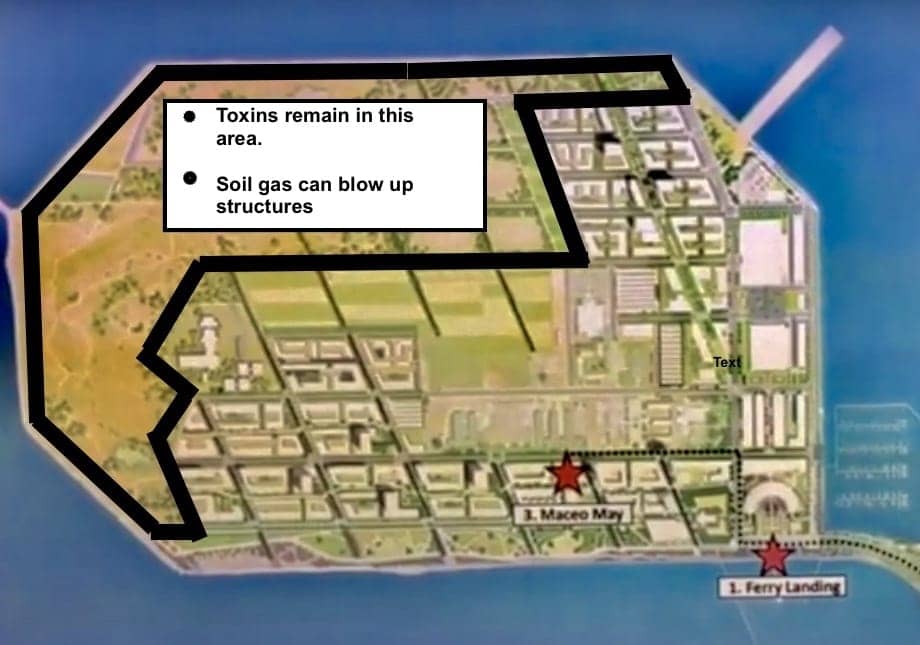

Fair warning

Because a major portion of the Golden Gate side of the island is restricted to “Limited Land Use,” buildings cannot be constructed there as barriers against sweeping western winds. Not only does the land remain too toxic for construction, but soil gas can expand inside structures and blow them up.

Diagonal roads can’t block powerful ocean winds. High rise towers always create wind tunnels in streets.

Pretty toxic walk

To shield themselves from dust, the resident wore a head covering and aviator shades over glasses. A mask protected their lungs. They traveled southwest on 12th Street toward San Francisco Bay. Crossing Avenue B, they followed the sidewalk between townhouses 1310 and 1312 Gateview Avenue.

At Gateview Avenue, looking left over a meadow, they could see the misty silhouette of the San Francisco skyline suspended on the horizon.

Denial or acceptance

Treasure Island residents live with denial or acceptance that their yards, parks, pathways, streets and townhouses are polluted, but most have nowhere else to go in the Bay Area’s out-of-control rental market.

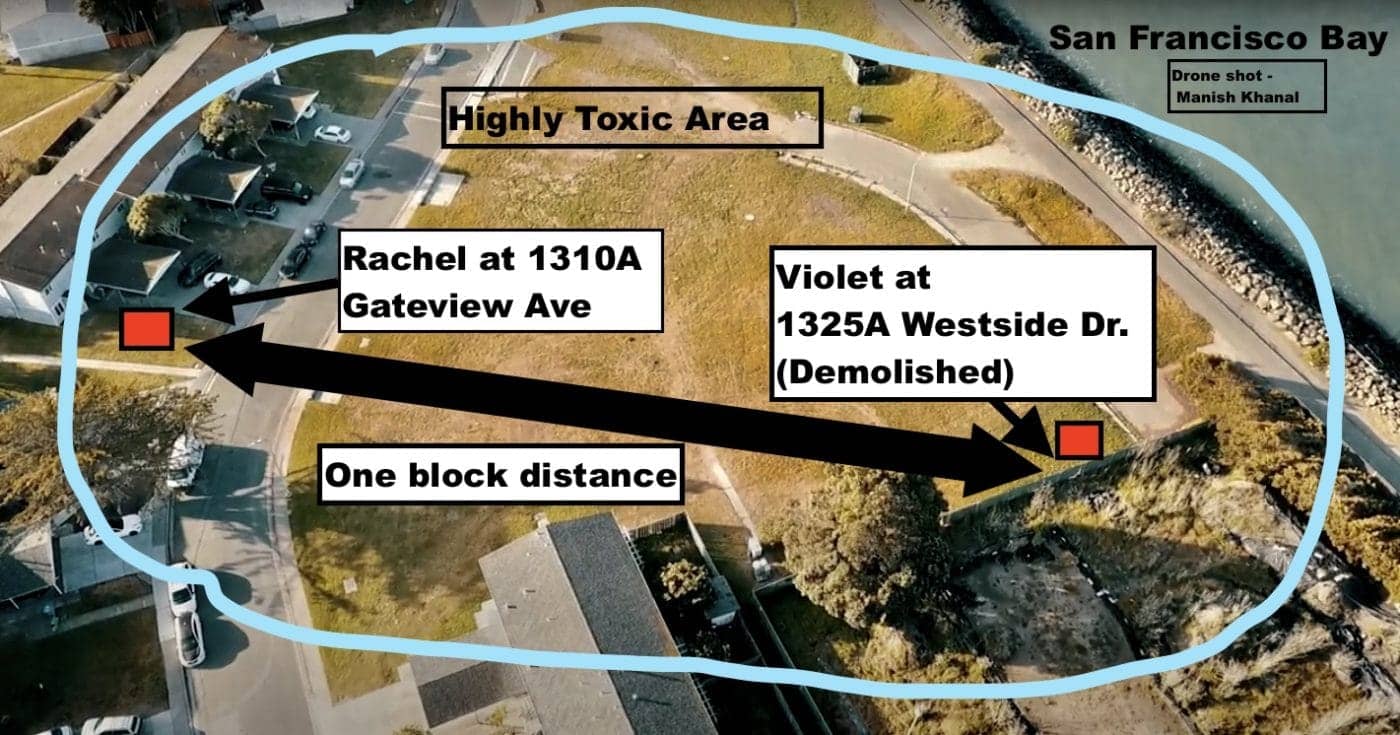

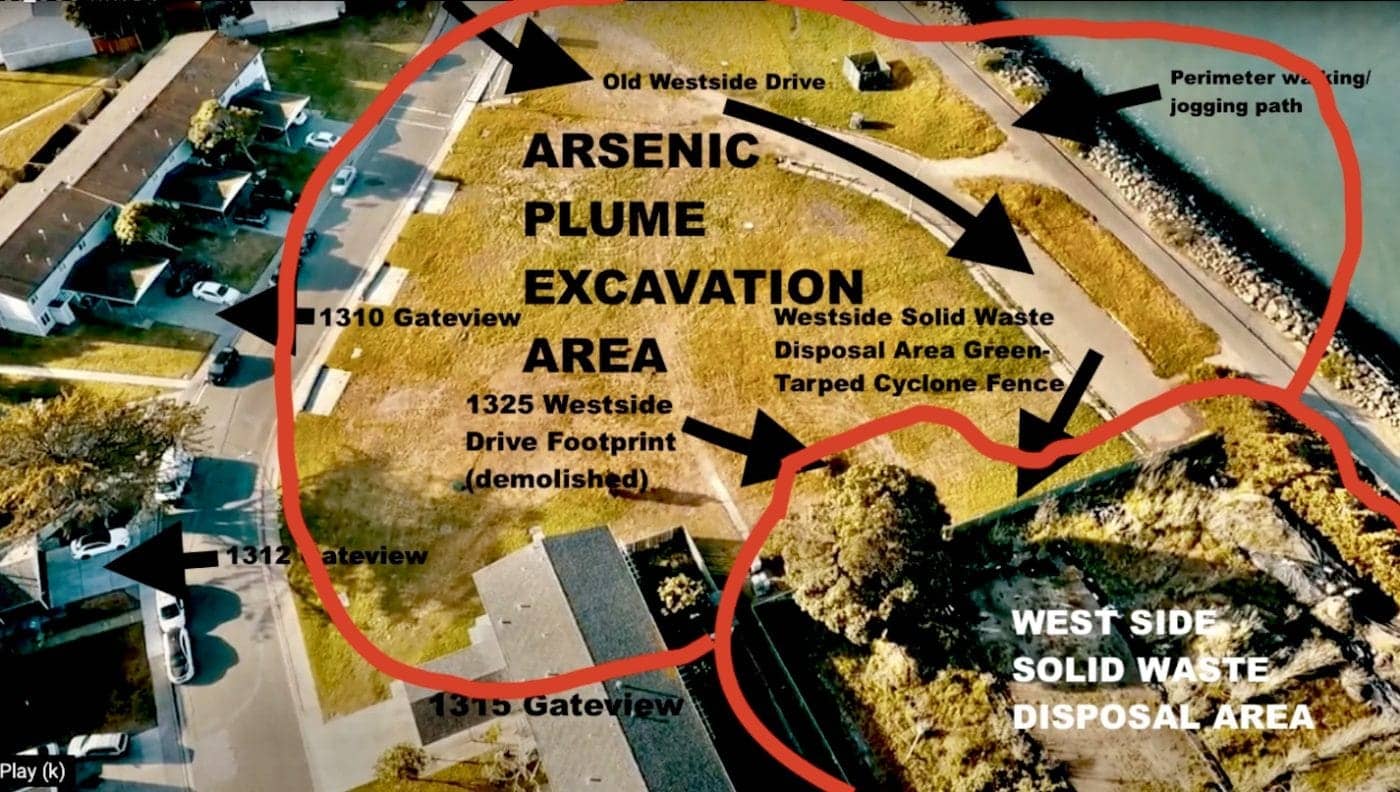

Passing the green meadow at the intersection of Gateview Avenue and old Westside Drive, the resident risked exposure to a poisonous witch’s brew the Navy missed during its decades-long toxic cleanup. Facing the Bay, they saw a contaminated area comprising the meadow and the Westside Solid Waste Disposal Area.

Radiation, the chemicals napalm, benzine and dioxin and the heavy metal arsenic lurked in the groundwater, soil and air. Until their walk that day, they believed that distance and fencing around cleanup zones protected them. However, they didn’t know the Navy was detonating weapons in the area they were walking through.

Former islanders were poisoned in this area

In 1991, Rachel Sullivan, a Navy instructor’s teenage daughter, suffered excruciating migraines and epileptic-type seizures at townhouse 1310B Gateview Ave.

A block toward the shore, at 1325A Westside Drive, student Violet Andry Anaya also suffered seizures in 2007.

Rachel and Violet lived one block apart from each other in this highly toxic area. Though they were separated by 15 years, the same radiological and chemical neurotoxins left in the soil made both women sick.

Violet was sandwiched between toxins in the meadow and the Westside radiation dump. From February through September 2007, workers stirred up dirt next to her backyard. “I lived in the waste,” she recalled. Toxic dust clouds were so thick the Navy plastic-wrapped her windows.

In 2014, radioactive waste cleanup specialist and whistleblower Robert McLean found off-the-charts radiation under rocks at the shore where Violet sat with her morning coffee enjoying the view of San Francisco across the waves.

After these exposures, Violet suffered severe neurological damage. For years, she has been disabled by tremors, nausea, dizziness and inability to stand.

Naval operations left Treasure Island radioactive

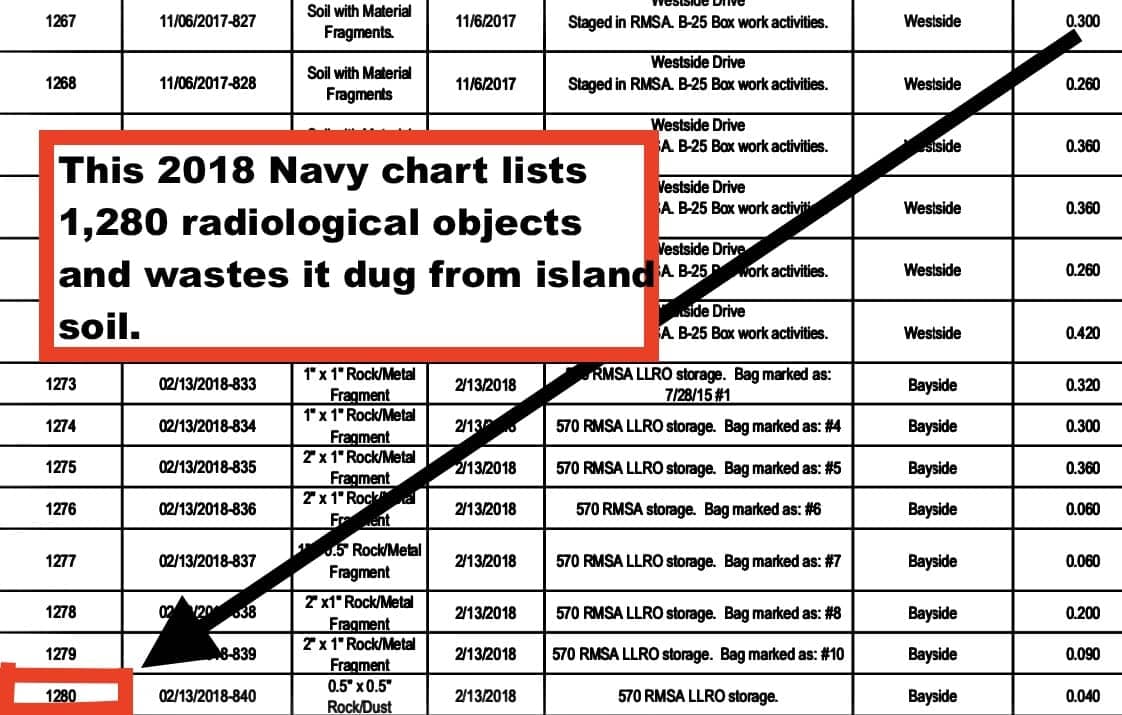

Charts posted by the Navy in 2018 list 1,280 radiological objects and wastes it dug from island soil. Radiation was spilled, leaked and dropped across the island from many sources and in many ways.

Anecdotal reports from sailors tell of 1940s and ‘50s “treasure hunts.” Instructors buried radiological objects for students with Geiger counters to find. According to researcher James Pepper, this was standard practice across Navy bases.

In his definitive article, “Treasure Island cleanup exposes Navy’s mishandling of its nuclear past,” investigative reporter Matt Smith describes “a history of mishandled radioactive material.” Radiation leaks occurred in schools and labs the Navy ran from the 1940s to the 1980s.

Navy charts list the deceptively named “low level radiological objects (LLROs)” that workers found in the soil. Some were remnants of ship repair. Others were used “throughout the Naval Station” in smoke detectors, exit signs, sound-powered phone jacks, check sources for radiation survey instruments, radio-luminescent dials, gauges and deck markers.

Not only did LLROs contain powerful thorium-232, americium and strontium-90, but Navy charts also list foils radioactive enough to burn or kill. Foils were components of lenses and night vision metascopes assembled in the Building 3 optical lab. A 2014 Navy document states that radiation may have been washed from the lab down a lead-lined sink into the Avenue M pipeline where it could contaminate the entire island’s water system.

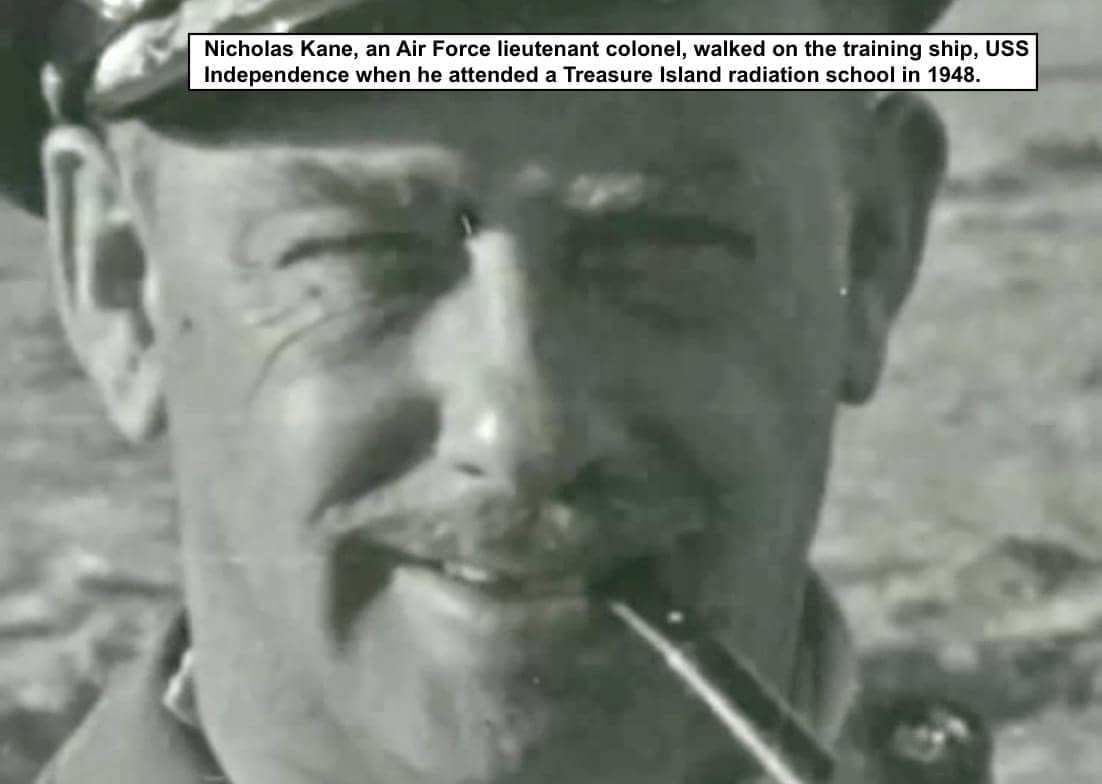

In 1946, after the USS Independence was bombed in Bikini atoll nuclear tests and returned to Treasure Island, Air Force Lt. Col. Nicholas Kane’s letters described wandering across the warped flight decks of this ship when it was used for nuclear training in the Navy’s Atomic, Biological and Chemical Warfare Schools.

In 1950, the Island’s largest radiation spill occurred in a lab in Building 233 on Avenue M. Radioactive desks, chairs, rugs and other detritus from Building 233 were loaded on the USS Independence. According to researcher James Pepper, the Navy sank the Independence not near the Farallon Islands, as many have written, but rather into “what is now the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary.”

In April 2013, reporters Matt Smith and Katharine Mieszkowski discovered cesium-137 levels three times higher than previously recorded in the soil behind Building 344, an underground radium vault sunk between two RADIAC schools, Buildings 342 and 343, still standing on Avenue M in July of 2021.

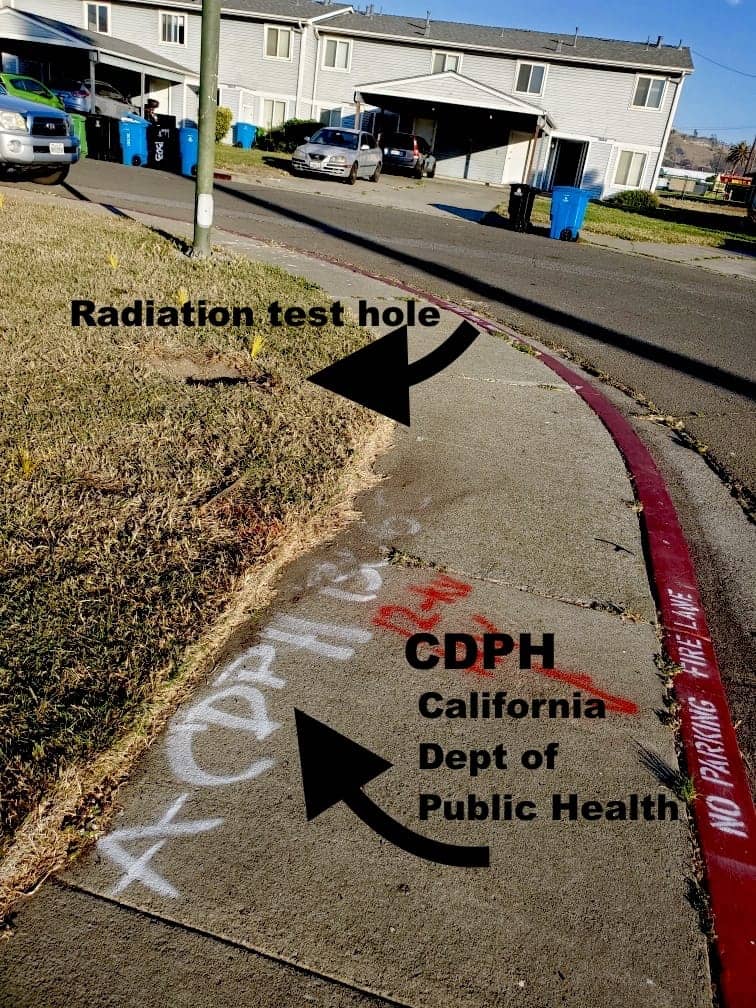

Re-scanning for radiation goes on. In summer 2021, a resident photographed a test hole in a Gateview Avenue lawn where the Navy had discovered a highly radioactive foil in 2014, eight years before. In a December 2021 meeting, Navy officials said the letters “CDPH” spray painted on a nearby sidewalk was part of an identification number, suggesting the Navy itself, not the California Department of Public Health (CDPH), had been looking for more radiation.

How did the meadow on Gateview Avenue become contaminated with radiation, chemicals and the heavy metal arsenic?

In 1950, the largest radiation spill in Island history affected the area around the meadow. Someone spilled radium sulfate in a lab in Building 233, the RADIAC Instrument Calibration School located a half mile away at Fourth Street and Avenue M on the island’s Berkeley side. Navy reports stated that before the spill was discovered, “students unknowingly tracked the radiological material throughout the building” and into cars that drove across San Francisco.

Navy personnel were “cleaned” in a “Quonset hut type” “Chemical Warfare School Decontamination Building,” numbered 273, located just west of the meadow. For 71 years, radioisotopes with long half-lives had plenty of time to penetrate and lurk in the soil beneath the ground where the resident was navigating their wheelchair.

Fake atomic blast

The Navy also mishandled chemicals and heavy metals on Treasure Island. In 1957, chemicals were dumped in the ground during a nuclear war symposium when the Navy set off a fake atomic bomb blast. The weaponized chemicals napalm and benzene were sprayed into the Bay and over the water and land that would later become the meadow, a radiation cleanup zone and the heavily populated Gateview Avenue neighborhood.

How did arsenic get into meadow soil?

Navy accounts of how it introduced the heavy metal arsenic, a component of rat poison, into the meadow’s soil are unclear. However, during the 1939 to 1941 International Exposition, the side of the Island facing the Golden Gate was used as a parking lot and later a runway for planes. Underground fuel storage tanks could have rusted and leaked gas.

The Navy reported that Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons (TPH) – in other words, gas – converted into a huge arsenic plume or bubble that expanded beneath the meadow until workers finally dug it out in 2016.

Polluted groundwater is the most common source of arsenic poisoning. For 28 years, the Navy exposed Gateview Avenue residents to arsenic washing from the meadow through cracks in their potable water pipes.

After removing the bubble, the Navy re-seeded the tract of land that stretches in a brown-green swath to the shore. There, pedestrians walk and joggers run along a path under which arsenic could continue to lurk.

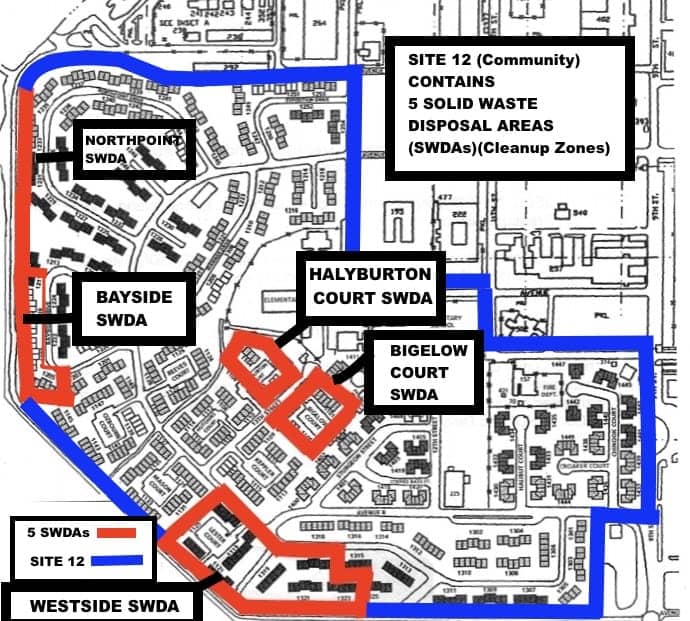

The Westside SWDA, or SWDA Westside

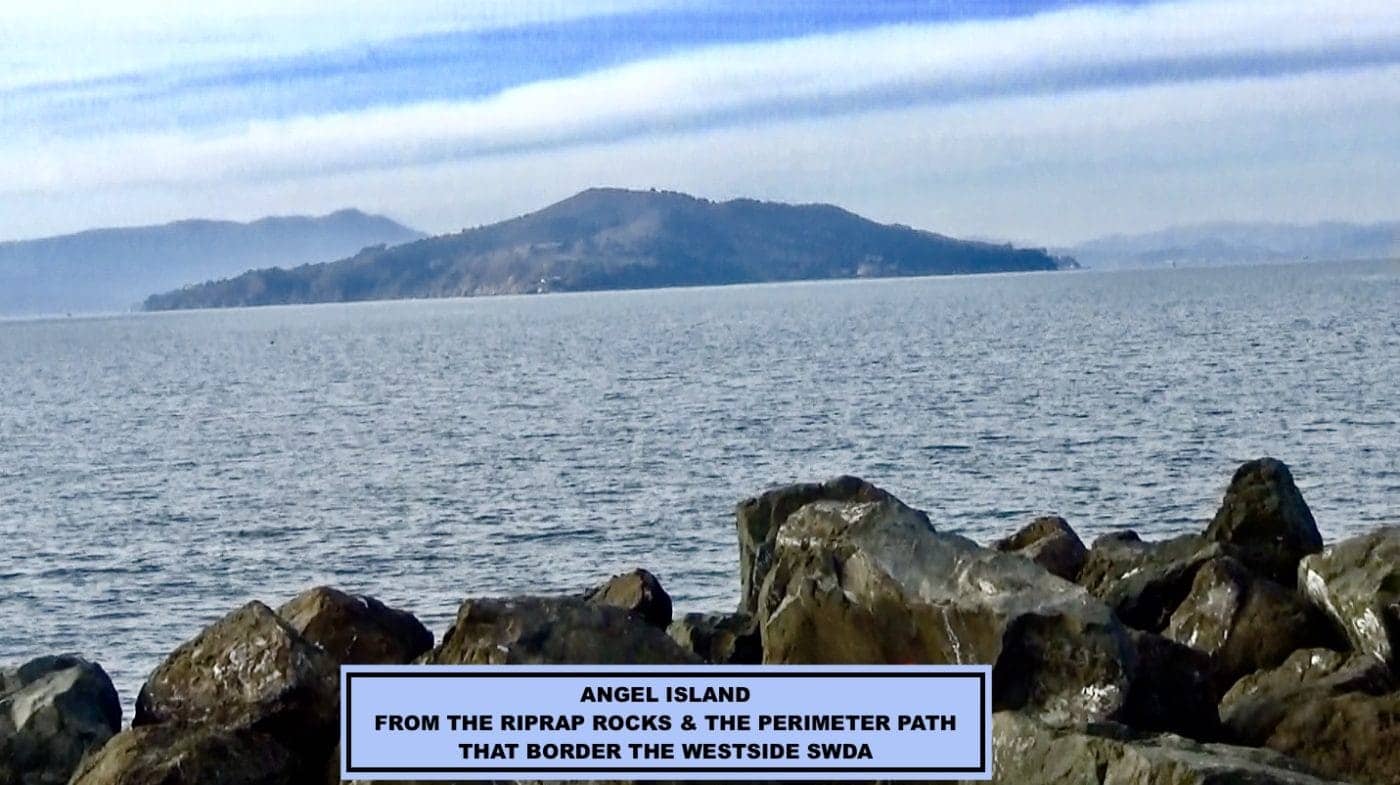

Across the meadow, the resident could see the western edge of a green-tarped cyclone fence surrounding the Island’s largest, oldest cleanup zone that curves along the shore.

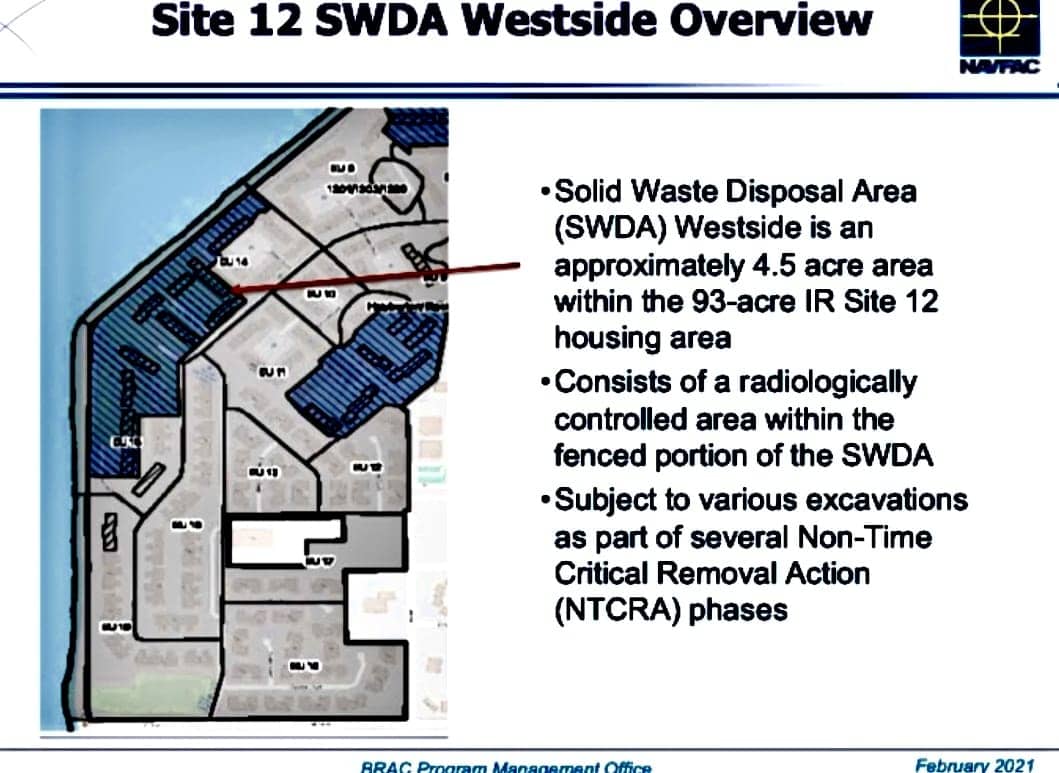

This map depicts the Westside Solid Waste Disposal Area, a 4.5-acre tract of land contained within the 93-acre housing area extending along the shore across from Angel Island. The Navy calls it SWEEDA Westside.

For 27 years, the Navy has dug out radiation, chemicals, petroleum and the heavy metals arsenic and lead from inside and around this toxic dump. From 1946 to 1963, the Island was poisoned when the Navy dumped its trash on the Golden Gate side, incinerating the garbage in pits and burn areas, reducing it to its chemical components.

In 1965, the Navy graded the soil and, between 1965 and 1985, erected townhouses over the pits. Then, the Navy realized they’d built homes on a toxic dump. At first, they thought the ground beneath the community was contaminated with chemicals. Later, they discovered widespread radiation.

In 1987, Navy officials stated it identified sites for further investigation. Comments to the press emphasized incorrectly that most of the radiation came from buttons handed out at the exposition that were coated in low levels of radium to make them glow.

In 1993, Congressional approval of closure and redevelopment of Naval Station Treasure Island jumpstarted the Navy’s cleanup into high gear. It erected fences around five areas in the Site 12 community where it claimed toxins were concentrated – Northpoint, Bayside and Westside Solid Waste Disposal Areas along the shore and Halyburton and Bigelow Courts surrounded by neighborhood homes.

In 2013, the California Department of Public Health criticized the cleanup as lax. The Navy reacted by intensifying its radiation scans of the entire island but narrowed its focus to cleanup work in the five Site 12 remediation zones.

Walking into danger

The little group crossed the street, turning right on Gateview Avenue. The resident wheeled along the sidewalk behind their companion and the dog.

To their left, they passed unoccupied townhouse 1315 standing outside the cleanup zone fence. They continued toward a Monterey pine and a green sycamore shading the front yard of the last unit in the townhouse.

. . . two yellow radiation signs were posted on the fence . . . out of the resident’s line of sight, concealing from the public the presence of radiation in this toxic dump.

From the green tarped fence that stretched in front of them, a large black and white warning sign commanded: “CAUTION! Area Under Environmental Investigation for Hazardous Substances, Unauthorized Persons KEEP OUT!”

Just beyond the trees, the cyclone fence snaked 50 feet off the sidewalk behind townhouse 1315. Recessed in a cul-de-sac,two yellow radiation signs were posted on the fence between the buildings and the cleanup zone, out of the resident’s line of sight, concealing from the public the presence of radiation in this toxic dump.

A few feet further, townhouse 1317 was enclosed inside the cleanup zone fence. The resident wheeled toward the end of townhouse 1317. A few feet beyond, workers and trucks are admitted into the cleanup zone from a Navy “access control point” at the intersection of Gateview and Avenue B.

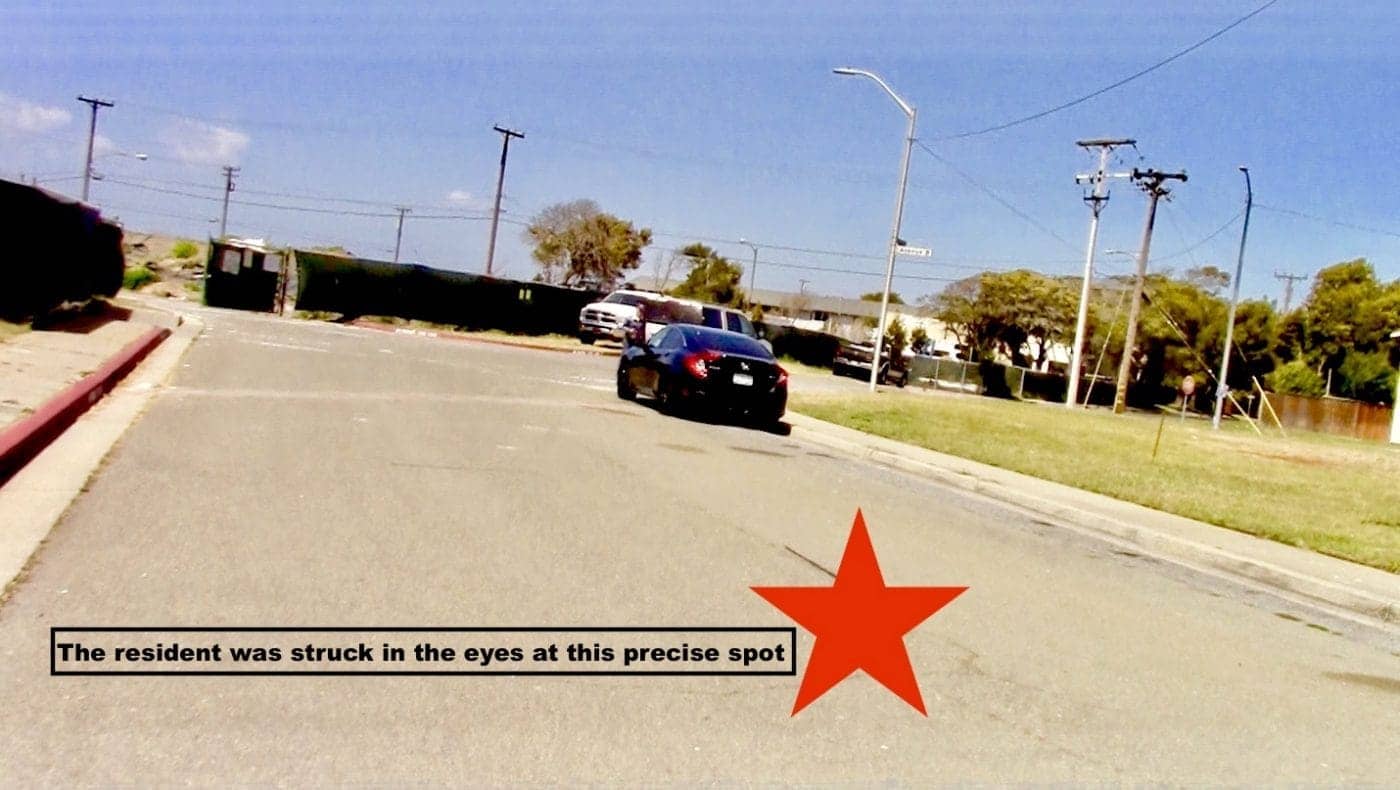

Across Gateview sits a bus stop in a small park. Suddenly, the dog darted across Gateview Avenue toward Canadian geese bobbing their black heads and necks up and down, snatching insects and seeds from the grass behind the Avenue B bus stop. The dog squatted briefly in the street. The companion followed.

The resident recalled, “I was trailing behind” the person and the pup “who had already crossed over to the field behind the bus stop. The direction we had just come from beforehand was calmer.” The 1317 Gateview Ave. townhouse had sheltered the resident from dusty wind blowing hard across the SWDA from the Bay.

An untethered tarp attached only at the top was flying, flowing and blowing from the cyclone fence like a rectangular green flag.

As the resident swung right into the street following the friend and the dog out of the protective shadow of townhouse 1317, the green tarp on the fence startled them by jumping up.

“A strong wind gust caught me off guard and hit with stinging force,” they said. “A blast of hazardous substances came tunneling through a gap in the tarp.”

“I felt an immediate sharp burning sensation in my eyes.” Double glasses did not stop grains of sand from scratching the whites. Grit shot down their throat. A thick chemical film coated their lips leaving a stinging, sunburned sensation under their mask. The skin around their mouth began to swell. “Dust and debris” stung and coated their scalp, face, neck, wrists and hands.

The resident never imagined that inside the toxic dump, the Navy was blowing up Mark II hand grenades and Japanese mortars or that shrapnel could strike them in the face. The resident began shooting photos and videos with their cell phone at 1:49 p.m. The filming was intended to pinpoint for the Navy and Toxic Substance Control officials the exact location of the blast.

. . . raising dust clouds as they scanned the dirt with metal detectors, before removing radioactive material and shards of metal from the dump.

“Inside the opening in the tarp,” they reported “two yellow radiation signs swinging horizontally in the direction of the wind on a rope hanging between two orange posts.”

In the distance, they saw “almost a dozen” cleanup workers wearing orange and yellow vests, raising dust clouds as they scanned the dirt with metal detectors, before removing radioactive material and shards of metal from the dump.

Shipping containers did not protect the resident from ‘hazardous fragmentation,’ aka shrapnel

When asked, the Navy did not disclose the exact locations it detonated weapons in the SWDA. Navy officials stated they were moving shipping containers around inside the SWDA to protect “nonessential personnel” from “hazardous fragmentation” – flying shrapnel.

However, this was questionable because containers lined with lead would be too heavy to easily move. The two rows of containers were also too far from the hole in the fence to protect people passing by.

On April 14, two weeks later, a young, healthy person passed the opening in the fence where the untethered tarp was still blowing, then walked rapidly across the street where the resident had been struck. The following day, their runny, itchy eyes and nose made them suspect “something on the Island.”

Attempts to heal permanent eye damage

When the resident reached home, the mirror reflected red striations in their eyes as if dust, sand, or metal shards were scratching under the lids. Pressing cool milk-soaked paper towels to their eyes and flushing with eye wash did not ease the pain.

After two months, their eyes felt sore and gritty. The red in the whites had turned pink. Only applications of warm wet tea bags relieved the pain. Four months later, it hurt to read. They worried their eyes were permanently harmed.

In two weeks, their facial redness and swelling went down only slightly. In three weeks, their lips remained red, burning, swollen and “pouched out.” They could not scrub the film off the skin around their mouth.

Their scalp, ears, neck, and the backs of their hands and wrists remained red, irritated and burned. The blast re-aggravated their throat and lungs. They suffered from a lingering dry cough.

To learn whether they were struck in the eyes by shrapnel, dust laced with a radioactive or chemical substances, napalm, benzine, dried tackifier or arsenic, the resident sought out doctors, the Navy, the California Department of Public Health and the state EPA’s Department of Toxic Substances Control, who promised help at the Feb. 8, 2021, San Francisco Board of Supervisors hearing on Treasure Island toxicity.

Next, we will describe the aid from these agencies that the resident did and did not receive.

Carol Harvey is a San Francisco political journalist specializing in human rights and civil rights. She can be reached at carolharvey1111@gmail.com.

Store

Store